Knowledge democracy is a phrase that refers to long-standing conflicts over what constitutes knowledge and whose knowledge counts. The phrase has been advanced as a kind of platform for resistance to the domination of what long-time scholar-activists Budd Hall and Rajesh Tandon (2017) describe as a small band of knowledge systems created by white male scientists in Europe some 500 to 550 years ago.[i] In essence, a much larger “global treasury of knowledge” has been suppressed and ruthlessly marginalized through the wielding of the Western canon of knowledge as a tool of colonization. This form of colonialism is not just the physical occupying of territory in which one more powerful group imposes itself on the land and resources of another group or groups. Rather, an entire enterprise of domination comes into play in which territorial, legal, economic, military, political and psychological means are employed to create and rationalize unequal relations that reach to the depths of assuming that the ways of knowing the world held by those acting as the colonizers are intrinsically superior to those who have been colonized.

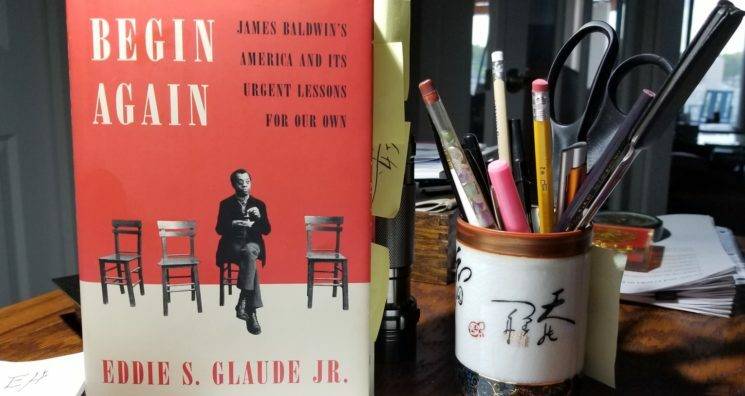

The dynamics of this process of domination, subordination, oppression, suppression and marginalization of knowledge, and the personal impact of these dynamics on the life of the African American writer James Baldwin are what Eddie S. Glaude Jr. explores in Begin Again. To be clear, Glaude Jr.’s book is not a manuscript about knowledge democracy. But in telling the story of what he refers to as “the lie” (p. 7) at the very core of America’s sense of its exceptionality Glaude is simultaneously unmasking the puffed-up epistemological violence used to perpetuate the lie and providing a timely example of the benefits for humanity, in particular humanity here in the United States, of breaking the grip of faulty assumptions about people and their lives.

In Glaude’s telling, the lie is “the mechanism that allows, and has always allowed, America to avoid facing the truth about its unjust treatment of black people and how it deforms the soul of the country” (p. 9). The work to be done in 21st century America to undo the deformity is both difficult to face and will be incredibly painful to do. In tracing the path that Baldwin walked in his efforts to contribute to bringing the country to its senses and its true potential Glaude tells a story that is at once sad, hopeful and sobering. Looking beyond the anger, the rage, and the crushing burden of historical disappointments from past failed efforts, Glaude sees in Baldwin’s journey the contours of choosing life even in the thick of ceaseless oppression and psychological colonization. Ultimately, Baldwin found, we can find our way to a new sense of our shared humanity, a salvation if you will, predicated on “accepting the beauty and ugliness of who we are in our most vulnerable moments in communion with each other” (p. 213). In this space “a profound mutuality develops and becomes the basis for genuine democratic community where we all can flourish, if we so choose” (pp. 213-214).

As I indicated in my previous blog, On Reading the World in 2020-2021, reading the world today is a crucial task if democracy in this country is to survive. Setting aside for now the facile notion of “learning loss” being bounced around as yet another way to ‘get back on track’ with rote learning tied to preparation to fit into the world as now narrowly conceived, the capacity of reading to open us to the world in new and rejuvenating ways can be mobilized positively to initiate a new sense of civic literacy and responsibility based on a revitalized sense of shared humanity. In a sense, the reintroduction of Paulo Freire’s “culture circles” is as important to the repair of the civic infrastructure of America at this time as is the legislation proposed for the repair of our physical infrastructure. Paradoxically, perhaps the efforts of many state legislatures to once again line up behind the big lie and suppress all efforts to help our children and youth learn to read the world as a part of their K-12 experience opens up new space for community-based popular education initiatives such as a new flowering of freedom schools, weekend civic literacy retreats, etc. that are grounded in knowledge democratization, bring renewed vitality to social imagination, and support linking literacy to social action for creating a better world.

Hall and Tandon discuss knowledge democracy as consisting of three interrelated phenomena – first, the existence of multiple epistemologies, or ways of knowing; second, the affirmation that creating and representing knowledge from within diverse epistemologies takes many forms, “including text, image, numbers, story, music, drama, poetry, ceremony and meditation”; and third, that knowledge is a powerful tool for taking action to work towards a more just and healthy world. Hall and Tandon also assert that in the context of knowledge democracy, these three phenomena are to be approached through “open access for the sharing of knowledge, so that everyone who needs knowledge will have access to it.” Eddie Glaude’s timely and loving examination of the powerful lessons in the writings of James Baldwin and the urgency of these lessons for our times is a helpful example of what a scholar-activist can contribute in pushing back against knowledge monopoly and placing what has previously been relegated to the category of subaltern knowledge at the center of the conversation regarding this nation’s future. The use of the text and the knowledge infused throughout its pages as a part of a new generation of culture circles also might be a fine example of open access for the sharing of knowledge, in this case knowledge that can help us face the nation’s big lie and begin working together to create a new path forward.

Next up: Browsing through my books following my reading of Begin Again, I found one that I had carried around with me for more than 50 years but had never opened. I don’t recall how I came to have the book, but will forever be grateful for my stubborn lugging it along through move after move. This book – Blake or The Huts of America – is a novel by Martin Delany (1812 – 1885) which appeared in fragments published in 1859 and is cited as “the first novelistic offering of a black writer to be published in the United States.” In the next blog I will share some thoughts on this amazing and challenging book.

Reference

[i] Hall, B. L. and Tandon, R. (2017). ‘Decolonization of knowledge, epistemicide, participatory research and higher education’. Research for All, 1 (1), 6–19. DOI 10.18546/RFA.01.1.02.

Lonnie,

Thank you for your reflections and wisdom.

The big question for me is: How do we encourage more people to cultivate knowledge democracies in their schools, organizations, and communities?

With appreciation, Rolla

Thanks, Rolla., Yes, that is the big question. Although I would love to see policy-action taken on the national and state levels to establish and fund civic literacy initiatives grounded in the better angels of democracy, I imagine we first will need very small scale local projects. Some may be based in school districts that understand just how serious is what Henry Giroux calls “the violence of organized forgetting” (in other words, the systematic destruction of a civic literacy tied to democratic values). Other initiatives will be after-school and weekend community-based projects that can be based on an updated reading of Freire in reference to ‘democratic culture circles. There are lots of creative young people out there who can take the lead on this. . .