INTRODUCTORY NOTE: I have been in a period of personal and professional reorganization following a major health scare. From June through September I was in treatment for throat cancer following 2 months of diagnosis and testing. The chemo and radiation therapy I underwent destroyed what had been a malignant tumor at the base of my tongue, and this good news has brought much relief. I am now in the post-treatment “watch” period before my doctors determine if I can be classified as “in remission.” So far all signs are good in the watch period. I cannot thank enough all the healthcare workers I have interacted with over the past 10 months! My absence from this Blog was made necessary by the focus on and energy required during the treatment. The post below is my return, and although I am happy to be back at it I am saddened by the circumstance we all now face in a world in which democracy is under direct attack.

A Morning After: Ukraine, Putin, and the Attack on Democracy

On February 23, people in the US who were tuned in to the news of the growing tensions in the Ukraine witnessed the start of Russia’s invasion of that country. My return to blogging comes the morning after the invasion began.

As historian Heather Cox Richardson (2022) wrote in her e-newsletter on February 23 regarding the invasion “It not only has broken a long period of peace in Europe, it has brought into the open that authoritarians are indeed trying to destroy democracy.” Here, I believe, is the crux of the matter for those of us who value action research and all forms of participatory and practitioner research. To the extent that we understand that the spirit of democracy lies at the heart of our approaches to knowledge production and dissemination, we understand that the terrible plight of the Ukraine is our plight as well. The effort to destroy democracy, if it is allowed to proceed unchecked, will without a doubt come knocking at the doors of those who encourage, nurture, and engage in participatory research around the world.

As I have written over the past several years, participatory and practitioner research are fundamentally rooted in an opposition, even if weakly articulated and lacking in well formulated strategy, to knowledge monopoly in all its forms. Our dearly missed colleague Susan Noffke asserted in 2009 that those using the term “action research” seemed clear in their “assumptions about the kind(s) of knowledge they seek to enhance” as well as the traditions adhering to their work – the ends towards which such research is aimed – and the links between action research and movements for social change. Importantly, Noffke also pointed to areas in which we needed to keep a close eye on our own potential for complacency. In Noffke’s view, caution must be taken to not rigidify action research as merely an accepted ‘method’ within higher education, or social science in general, at the expense of its true significance and centrality as a way to support movements for social justice. It was essential, that is, to stay close to a politics of knowledge that would keep our integrity intact even in the face of the grinding corruption and cooptation of greed-dominated and corporatist-capitalist notions of knowledge economy. As Orlando Fals Borda (1991) helped us to understand more than four decades ago, the great potential of participatory research is in correcting “unequal relations of knowledge” through the uplifting of popular knowledges and ordinary people’s lives. Absent the recognition of inequality in relations of knowledge, action research and all forms of participatory and practitioner research can too easily become ways to rationalize oppression and colonialization and its narratives that marginalize and silence the voices of the systematically disadvantaged.

In this context, all forms of participatory research are best viewed in the spirit of the conservationist and activist Terry Tempest Williams’s statement that “democracy is best practiced through its construction, not its completion” (2004). When mobilized properly, participatory and practitioner research contribute to the construction of democracy, in particular in relation to its practical and localized intent. With this ‘constructionist’ orientation it is pretty obvious that participatory research has important potential to provide antidotes to what Henry Giroux (2014) discusses as “the violence of organized forgetting.” The closer we are to the real ground of people’s daily struggles to maintain dignity, create meaningful lives, and push towards the promise of democracy, the more likely we are to build new ways of thinking and acting that take us beyond stale and corporate economy notions of law and order, education reform, immigration reform, and any number of key social issues too often reduced to trivial media sound bites and cramped narratives regarding American values and needed solutions.

In Giroux’s view, a kind of civic death is fostered through mainstream discourses that promote “a malignant characterization of disadvantaged groups as disposable populations.” This pathway, he asserts, is what explains “the right-wing charge that the poor, disabled, sick, and elderly are moochers and should fend for themselves.” It represents a kind of imposed cynicism. Participatory and practitioner research provide a way to push back against this hardening of our culture and help open space for creating alternative narratives regarding the promise of democracy and hope for the future. Of particular interest to me, and I hope to many others, the pathway of knowledge democracy provides a direction for a much-needed rebirth of civic literacy in the US and other countries. Civic literacy incorporates the knowledge and skills needed to participate effectively in civic life “through knowing how to stay informed, understanding governmental processes, and knowing how to exercise the rights and obligations of citizenship at local, state, national, and global levels” (Morgan, 2016). Much of the current misinformation-filled rhetoric mindlessly adopted by segments of the American population, including the susceptibility to the craziness and lies of Trump and his coterie of conspiracy theorists, results from the massive failure of the nation to focus attention on the currently deplorable state of civic literacy.

Civic illiteracy feeds populist authoritarianism, and conversely such authoritarianism, once established, demands that any semblance of civic literacy be eradicated and replaced by obedience to a dominant Big Lie. Believing Putin’s lies about the Ukraine and his invasion of the country takes a good dose of civic illiteracy, as such beliefs entail not being informed about European history, cultures and politics, in particular regarding developments in Eastern Europe over at least the past 77 years, not understanding sovereignty, not understanding the importance of the United Nations as a means of encouraging peace and stability (even in the face of its shortcomings), and in the case of the US, not understanding just how dangerous, treasonous, and undemocratic are the rantings of Trump and his clique.

Current brands of authoritarianism, in their domestic Trumpian forms as well as their global Putinian and Xi Jinpingian forms, cannot accept knowledge democratization because of its potential to reinvigorate civic literacy, in other words. Introducing youth to racism, sexism, homophobia, islamophobia, and the full range of ideological, institutional, and environmental poisons of human progress through education is to invite them to imagine a better future and to begin to create new narratives of socio-cultural solidarity, empathy, and progress towards a better, more sustainable future. We see this time and time again in Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR), with young people able to navigate the difficult conversations in which voice is given to the truths of historical trauma and the possibilities for reconciliation and acceptance of difference.

The current pandemic of right-wing populist authoritarianism points to a deep-seated psychological and emotional rejection of invitations to listen and learn through respect for diversity and recognition that the construction of democracy is an ongoing task, with each generation called to the task in relation to evolving historical issues and challenges. Thus, as many perhaps otherwise patriotic Americans jump in line to support Trump’s treasonous love for all things Putin, they are unable to see Putin’s vision and actions as rooted in a profound hatred of the democratic values that these same Americans say they uphold. They cannot see past the lies of Trump and Putin because they are victims of what Giroux (2014) calls the “disimagination machine” that crushes the shared bonds and responsibilities and historical memories that are the lifeblood of community and democracy. Again, it is not an ‘informed’ democracy that holds the interest of right wing authoritarian populism. As we saw on January 6, 2021, inflaming authoritarian passions mattered more than the counting of votes associated with politics in a democracy, while understanding the centrality of the vote in a democratic society requires some civic literacy. In such circumstances, whether producing “dissident knowledge” or contributing directly to a revitalized civic literacy, all forms of participatory research can play an important role in strengthening democracy.

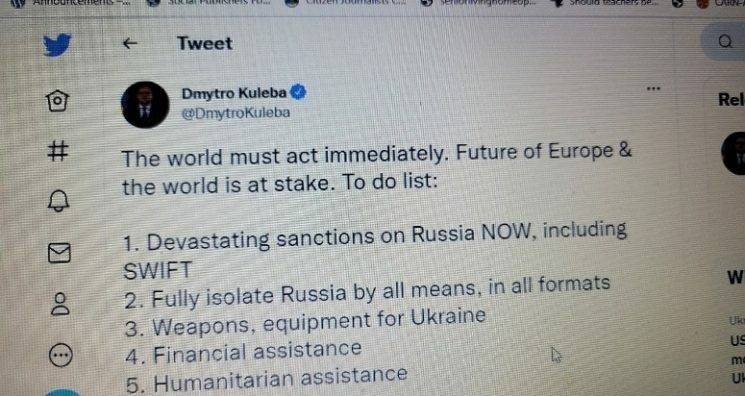

As the first hours of Russia’s invasion unfolded, Ukraine’s Minister of Foreign Affairs tweeted, “the world must act immediately.” Based on his conviction that the “future of Europe & the world is at stake,” he provided a five item to-do list that reflects both the immediacy of the crisis and the severity of what the Ukraine is now facing. For the global action and participatory research community I would add an item admittedly looking ahead but also incorporating our shock and sadness in this moment: My plea is that we mobilize our networks, establish platforms for discussing how knowledge democracy can be further stimulated and mobilized directly in the face of any and all authoritarian initiatives to crush democracy and silence our efforts, and build bridges between existing platforms that explore the potential for new global solidarities in democratizing knowledge and hence strengthening democracies.

References

Cox Richardson, H. (2022). https://heathercoxrichardson.substack.com/p/february-23-2022?utm_source=url

Fals Borda, O., & Rahman, M. A. (Eds.). (1991). Action and knowledge: Breaking the monopoly with participatory action research. NY: Apex Press.

Giroux, H. A. (2014). The violence of organized forgetting: Thinking beyond America’s disimagination machine. San Francisco: City Lights Books.

Morgan, L. A. (2016). Developing Civic Literacy and Efficacy: Insights Gleaned Through the Implementation of Project Citizen. i.e.: inquiry in education, Vol. 8 (1), Article 3. Retrieved from: http://digitalcommons.nl.edu/ie/vol8/iss1/3.

Noffke, S. E. (2009). Revisiting the Professional, Personal, and Political Dimensions of Action Research. In S. Noffke & B. Somekh (Eds.). The Sage handbook of educational action research (pp. 6-23). London: Sage.

Williams, T. T. (2004). The open space of democracy. Eugene, OR: WIPF & Stock.

Further Readings

Hong, E., & Rowell, L. (2019). Challenging knowledge monopoly in education in the U.S. through democratizing knowledge production and dissemination. Educational Action Research, 27(1), 125-143.

Kuleba, D. (2022, Feb. 23). Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. https://twitter.com/DmytroKuleba/status/1496711163530424324.

Rowell, L. (2021, August). https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/practitioner-research-in-a-time-of-triple-crisis-when-too-much-is-not-enough/.

Rowell, L. (2019). Rigor in Educational Action Research and the Construction of Knowledge Democracies. In C. Mertler (Ed.). The Wiley handbook of action research in education, pp. 117-138. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell

Rowell, L., & Hong, E. (2017). Knowledge democracy and action research: Pathways for the twenty first century. In L. Rowell, C. Bruce, J. Shosh, and M. Riel (eds.), the Palgrave international handbook of action research, 63-83.

Spooner, M., & McNinch, J. (Eds.). (2018). Dissident knowledge in higher education. Regina, Canada: University of Regina Press.

Thank you for your eloquent thoughts. As our hearts are hurting for the Brave Ukrainian people and those who treasure democracy, it is wonderful to read your voice reflecting the truth and a hopeful path forward.

Thank you Sharon. Lifting our voices at this time is the least we can do.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge with us. I pray you to continue to get better. I will do my best to promote civic literacy and to continue learning.

Thank you, Virginia. I am hopeful that civic literacy and action research initiatives will find their way towards more visible collaborations. Best wishes.