Project Summary

The main research goal was to study some leaders’ experience in their struggle to implement and exercise the participatory democratic model in Venezuela according to Constitutional requirements. The focus of the research endeavor was twofold: (a) to enhance the Political Science body of knowledge to better understand how this particular Latin American democratic model operates at community levels and (b) to understand types of challenges experienced by community leadership in achieving greater amounts of happiness, political stability, and social security, as called for in the Constitution.

While interacting-acting with participating community leaders, these key findings emerged:

(1) The existing body of Political Science knowledge lacks adequate political conceptualizations of Latin American affairs. This is because of overreliance on colonial political knowledge and the use of outside research paradigms to understand Latin American political realities historically.

(2) There were political advancements according to the dreamed democratic model within the constitutional paradigm of Venezuela, such as, basing every major definitory decision according to the people’s will, and establishing participatory mechanisms to create and implement public policies to satisfy organized communities’ needs socially, politically, and economically. But, corruption, state paternalism, demotivation, and other top-down impositions hindered the development of the people’s consciousness. These barriers affected citizens’ participation processes at the heart of the participatory and protagonist democratic model.

(3) As a consequence, the essence of democratic development in communities is “the struggle.” It is the struggle to be understood within the community (Latin American) perspective and the struggle to exert a vivid participatory democracy from the bottom-up.

Overall, the participatory democratic model requires a new mentality to understand this democratic model scientifically but also to develop new political practices within this model. Action research approaches are needed to further investigate how the emerging practice of democratic paradigms is happening. Practical applications of this research are offered.

Project Context

The study was conducted in five marginalized communities located in Maracaibo city, Zulia state, Venezuela. Geographically, Maracaibo is located in the Northwest of Venezuela, and it is the largest and most populated zone after the Caracas Metropolitan Area (Capital city). Economically, Maracaibo has been known as the main oil management center in Venezuela. Culturally, the city is a melting pot of foreign influences and immigrants, such as Europeans (Italy, Portugal, Germany), Latin Americans (Colombia, Panama, Argentina), Asians (China, Japan), Middle-Easterners (Lebanon, Jordan, Syria), and Americans. As part of Zulia state, Maracaibo is also well known for its musical and scientific contributions. Politically, Zulia state has the largest electoral population in the country. Here, Maracaibo represents approximately 50% of all Zulia voters. Within this general context, the community characteristics in which the research project was developed were: low income, limited access to public services (water, housing, police patrolling, power) and economic constraints (unemployment and lack of financial aid), delinquency, corruption, and antagonism among members of the communities, and infrastructure deficiencies (schools, health centers, roads and public transportation, internet access).

Research Goal, Method, and Outcome

Background and Rationale

This study was built to respond to several political events that were transforming how Venezuelans understood democracy, as well as to address the knowledge gap regarding the participatory democracy model adopted by the Constitution of 1999. How to put this political model, in which the people were identified as the primary source of sovereignty, into practice in local communities was uncharted territory in the political science landscape. Therefore, field research based on community leader experiences in developing the participatory democratic model was needed.

The participatory democratic model in Venezuela was originated as a radical proposal to transform the country after several decades of popular discontent and national economic, socio-political, moral, and military collapses produced by the earlier representative democratic model based on the Constitution of 1961. According to this Constitution, political parties were the owners of the entire political system. As a consequence, popular discontent in the period 1961 to 1999 was directed not only against the representative democracy model, but also the political parties that were held responsible for the poor management of state matters. During those times, a common form of insult among Venezuelans was to be called a “politician” or “you are like a politician,” which meant to be a liar, corruptor, thief, or immoral person; in other words, an untrusted individual. As a result, the majority of Venezuelans did not want anything to do with politics and politicians (Arenas, 2001; De la Torre, 2009; Zapata, 2001).

Therefore, to transform the country it was pivotal to re-insert, re-motivate, and re-empower the people in the act of making politics. To accomplish this, the participatory democratic model put forth the development of high political consciousness among the people as a critical component. If the former representative democratic paradigm only admitted the people in the act of voting and marching, the participatory democracy paradigm summoned the people to actively participate in society as creators, proponents, voters, executors, comptrollers, and legislators in the political arena (Barreto, 2018; Constitution of the Republic of Venezuela/Congreso de la República de Venezuela, 1961; Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela/ Asamblea Nacional Constituyente, 1999; Daal, 2013).

In the midst of this social, political, economic, legal, military, and cultural reality, field research was most needed. Accordingly, the study “Leadership and political consciousness: A phenomenological study of the participatory and protagonist democratic experience” was developed (Barreto, 2018) A reflective phenomenological research path was chosen because democracy and phenomenology share principles. Democracy is understood as a form of government based on the congregation of zoon politikons (i.e., humans as political beings) (Aristotle, 2004) who meet to attend to their individual needs in coexistence. In this regard, addressing individuals’ experiences and aspirations within a community as a whole constitute the main philosophical principle of democracy. Meanwhile, phenomenology, as a research method, is based on the subjectivity and meanings created by individuals (persons) through daily living. Therefore, democracy and phenomenology share a common understanding of the individual as the main actor in their conceptualizations of personal and social life.

As Levin (1992) indicates, the endless democratic task is to create a freer and more human experience where “we all participate and to which we all contribute.” Levin identifies four ways in which phenomenology can serve democracy: (1) As a formative practice of the political being because the practice of phenomenology enhances the self-awareness process; (2) As a practice that promotes the recognition, respect, and validity of the “reality of all experiences,” which contributes to the pluralism of political currents because understandings of the state of affairs are not imposed unilaterally; (3) As a philosophy that multiplies perspectives and starting points by recognizing the irreducible distinctiveness (subjectivity) of each person or group in certain circumstances, moments, and spaces; and (4) As a science and practice that is nurtured by intersubjective dialogue, and therefore, improves the social conditions necessary for mutual understanding.

The current study followed qualitative research rationality according to the phenomenological onto-epistemological-methodological perspective of Moustakas (1994) within an interactive qualitative research design as suggested by Maxwell (1996). This research design is characterized by being flexible and dynamic and having the ability to evolve as the research unfolds (Barreto, 2009).

Research Goals and Research Questions

After adopting the Constitution of 1999, a set of profound transformations started in Venezuela. The emerging constitutional participatory democratic model initially was unknown at the popular level. Venezuelans were required to develop a new political consciousness capable of understanding and constructing the new democratic model in which they were demanded to be principal actors. Accordingly, this research was oriented to understand how the participatory democracy model was being built from the community bases. The following research goals were designed to understand ongoing community experiences intended to advance participatory democracy from the perspective of community leaders.

- To generate phenomenological analyses related to the development of the citizenry’s consciousness of the Participatory Democratic model given the contemporary moment of Venezuela.

- To understand how the citizenry’s political consciousness is functioning according to the Participatory Democracy model within the constitutional context of Venezuela’s Democratic and Social State of Rights and Justice.

- To explore how the human energy of leadership in localized community contexts develops the citizenry’s political consciousness for Participatory Democracy practices within the constitutional context of Democratic and Social State of Rights and Justice.

- To understand the leader’s phenomenological and community dynamic associated with the exercise of Participatory Democracy within the constitutional Democratic and Social State of Rights and Justice.

Research Questions

Based on the research goals, the following research questions were settled:

Primary Research Question (PRQ):

How is the phenomenological live-experience of exercising participatory democracy described from the community leaders’ perspective?

Secondary Research Questions (SRQ’s):

- SRQ 1: How is the citizenry’s political consciousness functioning according to the Participatory Democracy model within the constitutional context of Democratic and Social State of Right and Justice?

- SRQ 2: How does the human energy of leadership in communities develop the citizenry’s political consciousness for Participatory Democracy practices within the constitutional context of Democratic and Social State of Rights and Justice?

- SRQ 3: How is the phenomenological dynamic of leaders’ and community human energy used to exercise Participatory Democracy within the constitutional context of Democratic and Social State of Rights and Justice?

The conceptual context refers to the core onto-epistemological-methodological concepts that give theoretical and documentary support to the research, thus offering its gnoseological contribution (Barreto, 2012; Maxwell, 1996). There were seven core ontological concepts (democratic and social state of right and justice; participatory democracy; leadership and human energy; political consciousness; ethics; political principles; and common good) and one epistemological concept (phenomenology).

Methods and Techniques

According to Maxwell (1996) and Barreto (2009), methods and techniques refer to the set of steps, procedures and instruments that allow both data collection and data analysis processes.

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews and theoretical-documentary review related to the research topics were used.

For the interviews, a bank of semi-structured and interconnected questions was created according the Secondary Research Questions (SRQs) in three main areas: leadership, political consciousness, and participatory democracy. Some of these questions were:

- What is the role of leadership in the participatory democratic model? (Leadership)

- What is the role of ethics and morals in leadership? (Leadership)

- How have the people developed their political consciousness? (Political consciousness)

- How has consciousness translated to participation? (Political consciousness)

- How is the Popular Power exercised? (Participatory democracy)

- What is the meaning of participatory democracy for communities? (Participatory democracy)

Five community leaders were interviewed. They were selected according to the following criteria:

- Being a leader with knowledge of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela’s legal framework; mainly in relation to the Constitution (1999) and the Popular Power Laws created in 2009 and 2010.

- Have recognized leadership experience in the creation of community.

- Being or having been a leader with ethical behavior and recognized actions to develop democracy.

- Be willing to participate in a disinterested way in the research.

- Be or have been a leader whose political-community work is carried out or has been carried out in the Maracaibo Municipality, Zulia State.

- Be over 18 years old.

- Have the ability to adapt to the limitations of the researcher and the circumstances of the research.

For the interviews, there was a bank of ten potential interviewees. This bank was crafted in conjunction with the Escuela para el Fortalecimiento del Poder Popular (School for the Strengthening of Popular Power). Eight community leaders were contacted randomly. The first five people who met the referred criteria for participation in the research were selected. Participants included 2 males and 3 females, and their ages ranged from 25 to 55.

For the theoretical-documentary review, both electronic and printed files were considered, including:

- Specialized references directly related to the conceptual context

- Complementary references

- Scientific analyses of historical events

- Journalistic analyses.

Data Analysis

Regarding the data analysis processes, the epistemological-methodological path of Moustakas’ phenomenology was followed. In this sense, there were four analytical processes:

The Epoché. This is a vital and transversal process intended to help a thinker become more aware of biases and preconceptions. With the epoché, researchers should be able to understand their research intentionalities, paradigms, and predispositions better so that higher consciousness of how these may influence the research development is reached. The epoché was an analytical process at the beginning of the research and during the research development. As such, there was a Researcher’s Subjectivity Declaration prior the research development in which personal considerations were identified and exposed (brought to the consciousness level) in relation to: God, Life, Scientific Paradigms, Democracy, Leadership, Consciousness, and Venezuela. Later, during the research, there were specific moments that required a higher level of awareness, and this demanded the development of what was named as the Dialectical Exercise of Awareness. Based on the principle of serenity, this dialectical exercise was inspired by the Socratic “know thyself” principle and intended to keep the analytical distance between the researcher’s subjectivity and the community leaders’ subjectivity. For example, there were moments in which informants spoke about their issues and these had been foreseen by the researcher previously. When this happened, there was a high risk of reinforcing the researcher’s biases so that reaching a genuine and data-grounded analysis could not be possible. The Dialectical Exercise of Awareness helped the researcher in dealing with this and other situations (Barreto, 2018). See Figure 1 (Slider #2).

The Phenomenological Reduction. With this analytical process, the potential exposition of analytical themes emerged from textual descriptions (transcripts). These themes of analysis were organized in horizons and treated according to their capacity to respond to the SRQ’s. For example,

Figures 2 and 4 (see Slide #3 and #5) show the result of the phenomenological reduction for two Informants. Later, for each phenomenological reduction, a visual representation was crafted in order to complement the description; see Figure 3 and 5 (Slides #4 and #6).

The Eidetic Reduction (Imaginative Reduction). In this analytical process, the data (subjective experiences) was analyzed according to the universal categories of phenomenological research. For this study, intentionality, intersubjectivity, corporality, and temporality were the selected phenomenological categories to understand the phenomenological structures within which the experiential essence lies:

- Intentionality: this category reflects discovery in the act of making sense of the subjective experience. In other words, intentionality is the phenomenological category that reveals the motivation that organizes the subjective experience (Martínez, 2004; Moustakas, 1994).

- Intersubjectivity: this analysis leads to discovery of the immediate relationship with others that manifests itself in the “We.” Intersubjectivity reflects understanding that the human being is not alone in the daily reality of his or her life. The problems that are present in that reality make individuals see the need to recognize the existence of others who are similar (Schütz & Luckmann, 2003).

- Corporality: this analysis is tied to the physical experiences that all individuals have when they interact in the world: What does the individual do? What does the individual feel? What does the individual think? What does the individual endure? What does the individual listen to? How does the individual react? (Barreto, 2018; Martínez, 2004;).

- Temporality: this analysis leads to discovery of how the experience of time has been experienced by the individual. It is not about time as unit of time (seconds, hours, days, weeks, years, decades…), but how has time been experienced as a living present with a glow of the past (Fernández, 1997; Malavé, 2008; Vera, 2011).

In this analytical moment, the SRQ’s guided the phenomenological process once again. In-depth interpretations were crafted in which the four selected phenomenological categories informed the community experience of developing the participatory democratic model. For example:

- “Citizens’ consciousness still [temporality] reflects immaturity regarding the people active role in exercising popular power [intentionality]: we as a population [intersubjectivity] do not want to articulate with anything (public institutions, community organizations, political parties, social movements, private organizations), we want everything to be solved for us [corporality].” High connection to SQR 1 – Informant 3.

- “Nowadays, as a product of the accumulated experience, a maturation or collective awareness [intersubjectivity – corporality] has been gradually occurring [temporality] as a result of referred institutional practices and paternalistic leadership.” High connection to SQR 1 – Informant 3.

- “Conscious and transformative leadership, with the ability to see and feel [corporality], promotes human transformation individually and socially [intentionality – intersubjectivity], from learning the path traveled to interest in achieving the common good in democracy [intentionality – intersubjectivity].” High connection to SQR 1, SQR 2, and SQR 3 – Informant 3.

The Phenomenological Synthesis. This analytical process integrates the analysis of each interview from the standpoint of awareness of its phenomenological essences. Through phenomenological synthesis, the experiential essence was understood as a whole, and this can support the creation of a theoretical phenomenological approach to transformative leadership in the context of participatory democracy. For this specific research, the synthesis was composed by three interactive analytical moments:

- Integration of all interviews (imaginative reduction) according to each SRQ. In Figure 6 (Slide #7), there is a visual summary of how community leaders understand their experiences in developing the participatory democracy model.

- Theoretical contrasting of the interviews integration (theoretical-documentary validity).

- Creation of a theoretical phenomenological approach capable of responding the Main Research Question and explaining the phenomenological essence that informs community leadership experiences aimed at developing the democratic participatory model.

Validity criteria

The validity criteria regard the control mechanisms that sustain the scientific rigor of the research. These were utilized both in the data collection and data analytical processes. These were:

- Descriptive: to ensure this criterion, each interview was recorded electronically (audio) to produce transcripts.

- By participants (informants): to ensure this criterion, each interview analysis was reviewed with participants to confirm the analytical coherence.

- By auxiliary researchers: To ensure this criterion, the data as well as results interpretation and potential findings were submitted to a discussion with qualitative researchers who have had experience in the study of community development, leadership, and phenomenology.

- Theoretical-documentary: to ensure this criterion, the analytical product of the interviews was compared with related theoretical sources that explained the conceptual context. It must be clear that this in no way meant violating the phenomenological principles in terms of respecting the subjective experience of each participant. On the contrary, the theoretical-documentary validity was used to understand in a deeper way the community leader’s experiences. In addition, it also helped in discovering potential findings when the interviews revealed gaps between theory and real-world experiences.

Therefore, as can be seen, the adopted research design was highly interactive because: (a) the components of the model interact with each other dynamically; each of the components has implications for each other; therefore, it is not linear; (b) the qualitative design is capable of adjusting and changing as it interacts with the situation in which the study is being conducted. It is not rigid or predetermined, but it is emergent; and (c) the model creates opportunities for the researcher to unveil principles that help to approach the phenomenon in a contextualized and pertinent way.

Outcomes

Four general research outcomes were generated:

- A phenomenological map of citizens’ political consciousness in the developmental stage of the Participatory Democracy model.

The citizenry’s political consciousness is determined by two main circumstances: an unreached democratic dream (inclusiveness) and unsatisfied existential conditions (housing, health, education, work). Based on the Constitution of 1961, the leaders of Political Party’s leaders promised Venezuelans a democratic dream in which they could voice their aspirations, and these would be taken into account by politicians. Meanwhile, in theory the very democratic paradigm used (representative democracy) should have satisfied the existential needs of all the people. But these proclamations did not become real. When the participatory democratic model arrived in 1999, Venezuelans found themselves without any knowledge of how to develop this new political model. The new model emerged through a popular struggle to overthrow the clientele-partisan-representative democracy, but the leadership of this struggle did not know how to implement effectively the model across different political layers.

As a consequence, the participatory democracy model has followed a “trial and error” approach in its implementation. On the one hand, this has generated frustration and mental apathy in a large number of communities. On the other hand, people were holding on to their enthusiasm because, finally, “the people” is being considered and recognized as the source of sovereignty.

- A phenomenological understanding of the symbolic significance of processes that emanate from community leadership aimed at fostering participatory democracy within the constitutional context of Democratic and Social State of Rights and Justice.

The participatory processes promoted by community leaders and the development of the citizenry’s political consciousness are together considered to be a “titanic task” due to two main factors: educational challenges and legal barriers. Educationally, developing the citizenry’s political consciousness requires profound and ongoing efforts, and this is a leadership responsibility. It is not about “giving” a scheme of patriotic values or information to certain communities but generating participatory processes of collective reflection that are capable of motivating the people’s involvement. In this regard, the symbol and consciousness of participation develop when people participate. The more people participate, and the better the quality of participation, the more and better the participatory democracy will be because leaders can use this participatory experience to deepen education for participatory democracy. The political consciousness of both the public powers and the people is in the process of building a political culture conducive to the conceptual and operational development of participatory democracy.

Regarding participatory democracy legislation, curiously, although the Constitution of 1999 states that participatory democracy is the mechanism to transform the society, the specific legal guidelines for the structure and practice of Popular Power were created approximately eleven years after the adoption of the new Constitution. Popular Power is understood as the instance that develops the participatory democratic model based on popular sovereignty. In other words, Popular Power is participatory democracy’s praxeological engine. If Popular Power is essential for a participatory democracy, why did the necessary legislation to guide and organize Popular Power take approximately eleven years to emerge? This situation hindered the creation of a new participatory culture so that new and old political parties maintatined a central role in the socio-political environment. Accordingly, the citizenry’s political consciousness recognized how powerful political powers are when it comes to making politics and attending to community needs. In fact, in different situations, political parties impose leaders on communities, instead of allowing the communities to select their own leaders as an exercise of participatory democracy and sovereignty.

- An explanation of how intersubjectivities in leadership are capable of promoting the exercise of participatory democracy.

In a related line of thought with previous research outcomes, intersubjectivities would promote the exercise of participatory democracy as long as these intersubjectivites are able to become a political power. This means that the infrastructure for active social movements, including community councils, and communes are needed to best resolve the social, political, cultural, and economic struggles. The underlying idea is to support and guide public institution agendas by means of the people, the organized people. Although many community leadership groups have been able to accelerate popular organizations and promote the creation of new community organizations, the community intersubjectivity is far from being the pivotal democratic element, as is required by the Constitution of 1999. Nevertheless, the evolution of the community organization, political consciousness development, community leadership enhancement, and the proliferation of patriotic sentiment have been exponential.

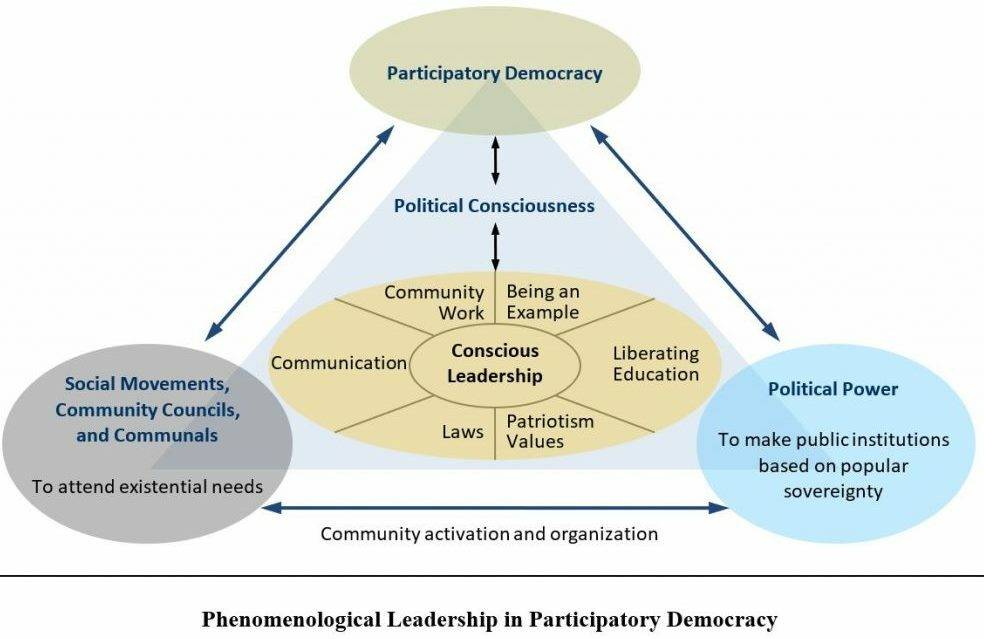

- An emerging theoretical-heuristic corpus design of human energy leadership and political consciousness formation as essential elements to generate a culture of protagonist participation in the context of a Democratic and Social State of Rights and Justice.

As a final result, the consolidation of a human energy leadership theory was crafted. Here, leaders are understood as the holistic conjunction of a communicator, manager, educator, and motivator: the C-MEM Leader of human energy. Within the democratic participatory model, which is inscribed in the Democratic and Social State of Rights and Justice context, the C-MEM Leaders would be the social agents for transformation. They would be able to recognize the community struggles and articulate the people’s will to overcome any challenge democratically, with high political consciousness, and inspired by patriotic values. This is not a leader who tells communities what to do and how to do it. On the contrary, the leader works with a community to craft and implement collective solutions for the good of all. As social agents with political consciousness, these C-MEM Leaders communicate, manage, educate, and motivate the community human energy to achieve synchronism of spirits and hearts, uniform tempering for effort and homogeneous disposition for sacrifice; simultaneity in the aspiration of greatness, the modesty of humiliation, and the desire for glory (Barreto, 2018; Ingenieros, 2008).

Reflections and Practical Applications of This Research

Based on the research findings regarding C-MEM Leader premises, the best community leadership practices to foster participatory democracy should consider the following interconnected reflections:

To engage communities based on empathy, consciousness, and hope. Community leadership is required to understand what communities are struggling with. This understanding should be an empathic understanding. Demagogical engagements will not produce positive results in terms of promoting the collective enthusiasm most needed to develop participation democratically. Being aware of community social, political, economic, and cultural needs empathically will allow the leadership dynamics to ignite community participation. The community members will understand how the leader is able to feel their suffering, pain, and aspirations for a better life. In parallel, democracy requires knowledge, and Participatory Democracy requires empathetic knowledge of the other. Accordingly, leaders should be community consciousness crafters and empathy constructers. Therefore, although leaders should be aware of the community struggles, they also must lead the community’s efforts toward greater awareness of their potentialities and opportunities of development so that these can be pivotal in motivating community participation. Hope is based on the awareness of potentialities and opportunities.

To respect the genuine leadership community dynamics. Community leadership should be part of natural community formations. Those leaders designated by political parties will be seen as strangers in communities. Furthermore, communities will react against those outside designated leaders since these outsider leaders challenge their own emerging leaders. Leadership is not a position of authority but a psychosocial dynamic among people who meet to reach common goals. Participatory democracy requires community leaders and leaderships coming from down-up. This is the essence of participatory democracy: freedom for bottom-up; not imposition from top-down.

To know the specific legislation and institutional interactions. Participation often is a sociopolitical mechanism that may have legal support which is operationalized by public institutions. Democracy requires understanding of these legislative and institutional interactions to channel community energy through proper and peaceful ways of participation. However, if the legislation and institutions are hindering community participation, leaders should be able to channel the community human energy through mechanisms capable of democratically transforming the legal and political reality by active participatory democratic actions. Understanding these issues may require training and fostering a higher level of consciousness among the citizenry.

To voice the popular sovereignty. Popular sovereignty is a constitutional right and primary premise in the participatory democratic model, both theoretically and praxeologically. Community leadership should be able to understand and embrace this popular sovereignty in order to voice its aspirations and demands. The people is the ultimate source of sovereignty, the guardian of the fatherland and State which are defended through democracy. A participatory democracy is stronger when citizens are free to exercise their popular sovereignty via active participation in resolving their shared concerns and needs related to their lives as part of their communities’ struggles for improvements and reaching better standards of life and prosperity.

To have exemplary morals. Morality is one of the most influential sources in developing strong and ongoing human interactions. As such, participation is a sociopolitical mechanism aimed at strengthening democracy, but this participation relies on the strength of the morality of both leaders and those they lead. In this regard, a moral and ethical education rooted in patriotic and life-enhancing values is pivotal in achieving a healthy and vibrant participatory democracy. Therefore, being moral is not only understanding a code of ethics but acting in accordance with the code, individually and collectively. Leaders should be the moral lighthouse of communities that aspire to develop a robust democratic participatory model capable of working for the good of all.

References

Arenas, E. (2001). Política, legitimidad y democracia en una sociedad en transición: las viejas y nuevas representaciones sociales sobre las nociones de política, partidos políticos y la sociedad civil bajo el impacto de la crisis social venezolana. Espacio Abierto, 10(2), 187-200.

Aristotle. (2004). La política [Politics]. Bogotá, Colombia. Ediciones Universales.

Asamblea Nacional Constituyente. (1999). Constitución de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela. Caracas, Venezuela: Gaceta Oficial extraordinaria N° 36.860.

Barreto, A. (2009). Liderazgo transformacional para la gerencia empresarial basado en la gestión del conocimiento y la innovación (Tesis inédita de maestría). Maracaibo, Venezuela: Universidad del Zulia, Facultad de Humanidades y Educación. División de estudios para Graduados.

Barreto, A. (2012). Metodología y diseño de investigación de una teoría fundamentada de liderazgo. Revista Copérnico, 8, 30-37

Barreto, A. (2018). Aplicaciones de la Fenomenología en Ciencia Política: Un Estudio sobre el Liderazgo y la Conciencia Política en Democracia [Applications of phenomenology in Political Science: A study about leadership and political consciousness in democracy]. United States: Independently Published.

Congreso de la República de Venezuela. (1961). Constitución de la República de Venezuela. Caracas, Venezuela: Gaceta Oficial N° 3.357.

Daal, U. (2013). ¿Dónde está la Comuna en la Constitución Bolivariana? Caracas, Venezuela: Taller Gráficos de la Asamblea Nacional.

De la Torre, C. (2009). Populismo radical y democracia en los Andes. Journal of Democracy en español, 1, 24-37.

Fernández, P. (1997) La evidencia predicativa. Apodicticidad como adecuación. En La posibilidad de la Fenomenología. Editor Agustín Serrano de Haro. Madrid: Editorial Complutense.

Ingenieros. J. (2008). El hombre mediocre. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Libros del Llano.

Levin, D. (1992). La fenomenología en América. Isegoría, 5, 119-133

Malavé, L. (2008). Liderazgo transformacional y gestión tecnológica (Tesis inédita de doctorado). Maracaibo, Venezuela: Universidad del Zulia: Facultad de Humanidades y Educación. División de estudios para graduados

Martínez, M. (2004). Ciencia y arte en la metodología cualitativa. México: Editorial Trillas.

Maxwell, J. (1996). Qualitative research design: an interactive approach. Thousand Oaks, USA: Sage Publications.

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, USA: Sage Publications.

Schütz, A. & Luckmann, T. (2003). Las estructuras del mundo de la vida. España: Amorrortu Editores.

Vera, B. (2011). Significado del autismo. Un estudio fenomenológico desde la perspectiva de la madre (Tesis inédita de maestría). Maracaibo, Venezuela: Tesis Especial de Grado. Universidad Rafael Urdaneta.

Zapata, R. (2001). El sistema de partidos de Venezuela. Una historia que aprender. Maracaibo, Venezuela. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 2, 199-225.

To cite this work, please use the following reference:

Barreto, A., & Vera, G. D. (2020, July 15). Phenomenological Leadership in Participatory Democracy. Social Publishers Foundation. https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/knowledge_base/phenomenological-leadership-in-participatory-democracy/