(Ir directamente a la versión en español.)

Summary

This is an interview with anthropologist and educator Marcos Guevara Berger about his PAR-based work with indigenous communities in Costa Rica. The work grows out of a project he was part of (in collaboration with Irìria Tsṍtchök , an indigenous rights organization) with civil rights lawyer Alan Levine, on “A Legal and Anthropological Inquiry into the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Costa Rica.” The interview highlights Marcos’ views, reflections, and experiences with PAR, this project, and other experiences he had and work he was part of. He elaborates on a range of broader themes, and shares his insights, about the relationship/collaboration between social science and the law; PAR, the university, and the community; the role of the state; the power of unearthing documentation; the limitations of a legal framework; whose voices and expertise matter; community resistance; having an impact; and how change happens. It is the voice and wisdom of a tremendous human being and educator.

Background

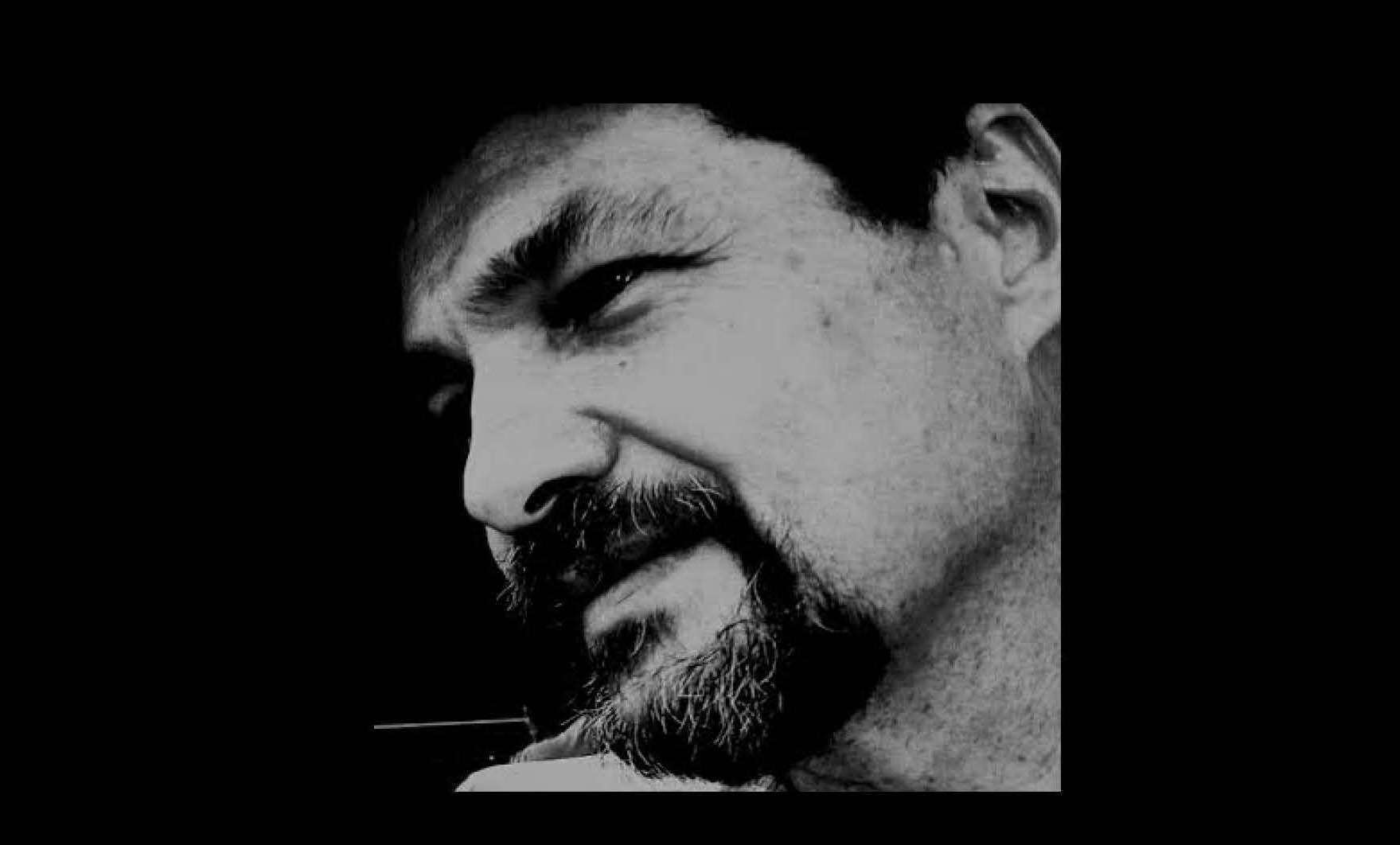

Marcos Guevara Berger[i] (October 5, 1958 – January 8, 2021), revered anthropologist, educator and researcher, was a dear friend, mentor, and great inspiration to PARCEO[ii] and to many of our team members who had the opportunity to not only take in his words but to experience his PAR-based work in action. Marcos worked together for years and years with Indigenous communities in Costa Rica, and his life’s work and way of being in the world fully embodied his principles and commitments to justice and to all peoples being treated with the respect and dignity they deserve. He will be sorely missed, but we know that his beautiful spirit and the impact of his wisdom will be with us forever.

The PARCEO interview with Marcos below was conducted by Krysta Williams on February 26, 2016 in Spanish at Marcos’ home in Costa Rica. The interview was translated into English by Chloe Villalobos and edited for style and clarity by Donna Nevel and Chloe Villalobos.

A report to the MacArthur Foundation, “A Legal and Anthropological Inquiry into the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Costa Rica,” describing a PAR-based project undertaken by Professor Marcos Guevara and civil rights lawyer Alan Levine in two indigenous communities, provides the context and background for the interview.

Participatory Action Research in Action: An Interview with Marcos Guevara Berger

In the interview, “KW” refers to Krysta Williams, the Interviewer, and “MG” refers to Marcos Guevara Berger, the Interviewee.

Participatory Action Research (PAR) and the University

KW: I’ve read the report that you wrote with Alan about your project, so I have some knowledge of that work. Could you begin by describing your work, its connection to Participatory Action Research (PAR), and the relationship between PAR and your teaching at the university?

MG: Okay. For me, working with participatory research — PAR is “IAP” in Spanish: Investigación Acción Participativa – is obviously always a very important occasion. I feel a very strong identification with this methodology. I feel that it is a fairer methodology in the sense that it does not put the interests of the researcher or the academic first, but it really starts from the proposals of the communities. The researcher is integrated into the process as a facilitator role, but not as the one who guides the whole process. They facilitate some things and can intervene in others, but ultimately they put a lot of weight on people’s interaction.

In academia this is not easy to do. I mean, the academic world seems to be very far away from this. Participatory Action Research does not set a deadline. That is to say, one starts processes that don’t generally have an end at a certain time so it’s not something that can be easily scheduled in the framework of a class. You can engage students about PAR, which I did, read articles and explore examples of PAR projects together, and discuss PAR principles, but there are very few occasions to do it. This is not something I was unaware of. Orlando Fals Borda himself–whose PAR work has inspired me greatly –explains somewhere that he was a sociology professor at the National University of Colombia, and when he began to work with PAR he had to leave the university. Because in the university there was no space for these things. So he developed his experience doing PAR. In a conference I heard, he said he would be invited by his students who became professors to speak about PAR at the university. But he never really integrated into the academic world.

It is unfortunately a problem because academia is established according to parameters of professional competitiveness, which so often puts the weight on knowledge acquired and certified by a diploma. And it moves away from the idea that knowledge can be found not only in books but also, significantly, in experience.

I also celebrate every time I can work with PAR because it is very important to me. It fulfills me personally, it satisfies me much more in reality than other things I have to do that are very far from that. Being engaged in a PAR process means being unsure of the outcome. That is to say, if the decision is made by a collective of people and not by a researcher, you will never really be sure what is going to come out of it. So for that reason it often doesn’t fit very well with the academic world.

Irìria Tsṍtchök, an Indigenous-led Organization in Costa Rica

KW: Thinking about the project you and Alan worked on together over 20 years ago now, I know you did it through the Indigenous-led organization, Irìria Tsṍtchök Foundation, which you were part of. Is the Foundation still around?

MG: No, not anymore. I have thought a lot about that, because I was quite involved in the creation of the foundation, although not as a founding member, but as a promoter of the idea. The foundation was created at a time when there was a rejection by the State to continue working on a ‘National Parks and Protected Areas’ approach together with Indigenous and farmer communities. Despite the state’s initial willingness to engage in a participatory process with Indigenous and farmer communities, it later withdrew its efforts because of conservative ideals. At that moment, the communities saw a need to create the Irìria Tsṍtchök Foundation, to continue the work that the state had abandoned.

Irìria Tsṍtchök was founded by Indigenous and farmer leaders around the Amistad Park, which was an area where we were working. What I see looking at it now from a distance is that it was created with specific objectives that were fulfilled. I think that the foundation accomplished goals that were important: To finance the communities; to strengthen the communities’ vision of their rights over those territories that were the “protected areas.” I believe that this was fundamental and continues to be important. So the foundation achieved the objective of consolidating the populations in terms of claiming their rights, in a way that made it hard until this day for the government to say that they are not going to take these populations and communities into account. See Slide #2 for Marcos Guevara Berger and Alan Levine in Action, 1993.

The Project’s Beginnings: Social Science and the Law

KW: Could you speak a little bit about the beginning of your project and collaboration?

MG: When Alan and I came together to prepare our PAR approach, we complemented each other a lot as an anthropologist and a civil rights lawyer. PAR is a social science approach and not one of law. At the same time, it was important to have knowledge on how to vindicate your rights from a legal perspective. From the point of view of law, it’s very rare for people to engage in a participatory action research process. It’s contrary to the traditional methodology of law. However, Alan’s participation as a lawyer was very important. For two reasons: first, because it really made the law something truly palpable and not just a set of rules. But on the other hand, and this was perhaps the part that I learned the most, it was also in the sense of understanding that the legal system, itself, will not solve things. That was perhaps a naïve vision that I had. The idea that if we get a good case, well justified, well put together, we are really going to win something and the community is going to win. And it really wasn’t like that.

Working With Two Communities: Cabagra and Guatuso

We thought of working together with two communities with different contexts and also with very different conditions: Cabagra and Guatuso, which I’ll describe in a minute. Briefly, the Guatoso work was more legally-oriented and the Cabagra work involved more of an internal organization issue. Initially, I thought that the legal focus in Guatuso was going to have a stronger impact on the rights of the community. Twenty years later, I see how the results of Cabagra, which were more about internal organization, had such a critical impact.

In Cabagra, I had already done work in and with the community before Alan and I began our work together. From that work and experience and the relationships I had built, I thought that Cabagra would be a good place to do PAR. It wouldn’t be like someone from the outside who just came to propose something. They knew it was not a matter of imposing an idea, but of generating something that they felt would be beneficial to them.

In the community of Guatuso, though I had never worked there, I knew a few people and also knew that there was a very strong land problem. It is a small community, and 90% of its land was taken over by foreigners. It has caused a very complex situation. The Malekus are few people, they are 1000 people. And most of them do not live in their community. They have to go out and work as employees and in the banana plantations. So they have a difficult situation because of the land.

A few years earlier, they had been involved in a land seizure. An organized group of the community invaded a farm that was within the Indigenous territory but had been taken over by cattle ranchers. So that experience, of which I was aware, seemed interesting. Here in this community there are people who really know what they want. They are determined. In Spanish we say “de armas tomar”, similar to the expression “a force to be reckoned with.” So we reached out to Guatuso and they let us know that “our issue is land, it is critical and we have to understand our territorial rights better.” We told them we would be interested in working together with the community to support them in the vindication of their rights.

Defining Community Focus

So, initially, we agreed to work on reclaiming land rights in Guatuso, and on community organization in Cabagra. In our discussions together, community members told us what they were interested in, what they could take advantage of, and which approach they wanted to take. That took multiple meetings. There is no time limit to define that. We agreed that the community could keep working at their own pace. We visited every fifteen days in each community to see how the discussion was going, what they proposed to do, and if there was something that we should contribute. And so, it was maybe in the second or third community meeting that more or less a theme had been defined.

Our role was to help facilitate the conversations and also to keep track of what was discussed in each meeting. We used, for example, a video camera, so at the end of each workshop we asked: who would like to make a summary of what we did today? Someone would synthesize, in their own language, and say: we discussed this, we reached such agreements and next time we will continue this way. This was important also because while there were people who always came, many times there were people who could not make it to a meeting, or there were new people who came, so we tried to start the meeting by showing the video of the previous meeting so that they would not get lost. So that they could see where we were.

In Guatuso, we were exploring the possible impact of international treaty provisions concerning the rights of Indigenous peoples. We knew that the national legislation has been, and still is, quite ineffective in resolving land claims. But provisions of international treaties, in our legal system, have superiority of force with respect to the law. And claims of violation of those provisions can be presented directly to the Constitutional Court. We thought that people might be interested if they understood that they would not have to waste time in local courts, where they have never been successful, and that they could make their claim in the Constitutional Court which is superior to those local courts.

So, in Guatuso, we had to engage in a more informational process at the beginning. For example, to discuss together the difference between a human rights treaty and national legislation. They gave us tasks. We worked on this until it triggered a discussion about what they could really do. There were many differing perspectives, and we tried to help generate a climate where people with very different views could hear one another and express their opinions.

Unearthing Documentation and State Negligence

One of the things that we worked on with the people of Guatuso was the need to show that the state’s failure to act on their land claims was not new, but, rather, they had to demonstrate that they had in fact been making these accusations against the state for a long time. So they put together facts that proved this. For example, they told us that they had gone to visit the University’s newspaper and were interviewed by a journalist. With this information, and the date of the interview, we were able to search and find an article in the newspaper that said that they had made such an accusation. They had also kept letters they had written making these accusations against the state. So, we were able to pool our competencies. For example, we could search the library archives, or newspapers, and they could search their homes for their letters and so on. We were able to gather an interesting body of information that showed that, since the creation of the Indigenous territory, they constantly complained to the state and said “this is happening, this is what the law says, and you are not doing what you should be doing.”

They were able to really demonstrate that the state had failed to apply the law, and the Constitutional Court recognized that and the community won the case. To me, when the case was first decided, it really seemed that it was going to be something very important. Not just for the Guatuso case, but also, as a Constitutional Court ruling, it could have a universal value for all other cases throughout the country. That is, another community could demonstrate that the state was negligent in applying the law, and could use the same jurisprudence. However, the interesting thing is that the Guatuso legal case did not evolve as much as I thought it would.

The Legal System

MG: And that’s where I say that was the part where I learned the most from Alan, because my perspective on how the legal system works was a little naive. I thought that simply proving a right was enough. But after that comes a lot of actions, which involves lawyers, which involves lawsuits, so it doesn’t end. The state, in a country, let’s say, within the capitalist world, will not easily give in to the rights claimed by the community. It will always defend itself, and that is indeed what happened. So, even though there was a favorable judgment, afterwards came what is called the ‘execution of the judgment,’ which required lawyers and other legal processes. These could not be carried out because the community did not have the capacity to do that part without the accompaniment of a professional. The case of the Constitutional Court was different because the court did not require a lawyer. The constitutional chamber, when it was created to claim rights established in the constitution, determined that any format is sufficient. There is a very famous case here of a boy who shined shoes, a ten year old boy, who wrote his case on a napkin stating how his rights were being violated. He presented it and won. That was really interesting because no lawyer was needed. However, what comes after is where it gets difficult.

The State has an organ to defend itself, the state prosecutor. Because of this, if a community doesn’t have a good lawyer, it makes it really difficult to create the legal change that is wanted. I learned that in cases like this, it’s necessary to think in the long term. For example, when Alan and I were working in the community, there were no Indigenous lawyers. Taking on the case with an outside lawyer could potentially cause more harm and be disempowering. Today there are a few Indigenous lawyers, there is one in Guatuso even, and that is very empowering for the community.

The Work Continues and Is Inter-Connected

KW: Just a quick question, from your point of view, how do you feel about the process that was started looking back at it now?

MG: It was very positive in the sense that the community has knowledge of its rights and the capacity to demonstrate it. That part is certainly a gain and has had an impact on the community. On the other hand, I have to admit that I myself did not have a clear idea of how it was going to end. So of course, it’s a bit of a risk, so to speak. Well, it is not exactly a risk, because nothing was lost. But it is a risk in the sense of not knowing how it will end.

But perhaps it is important to remember that this work we did is just one small part among thousands of problems and work that is being done. The solution to everything else does not depend only on this. I mean, there are other struggles that have also been present and in which I have not necessarily been present, but they were there. And many have had an impact. Everything is connected, I would say. For example, the Guatuso community’s cultural production is centered around the use of rivers and forests’ natural resources. Even their ceremonial life is developed around the river. With the land issue, their access to the traditional sites they used was stolen. But the community did not give up and continued with their claims. It was a legal fight but also a political one rooted in the community.

Community Resistance Continues

And they have won some others. For example, three-four years ago, an Indigenous person went fishing in a river that was not in the territory but was associated with a wildlife refuge. The police came and arrested him, That’s when a legal case started because they prosecuted him for a crime called “offense to natural resources.” Later it was proven that actually his fishing was part of his traditional Malekus way of life. So, with the existence of an international convention that put custom before law, the state really had to give in. In that case, by demonstrating that this use of the river corresponds to an ancestral custom, the criminal law had no effect.

I think it’s important to continue human rights work and show that we really should not give up the struggle for rights. That principle generated by the community is so important. I feel that this has strengthened the community because they all have common causes. For me, the Malekus embody resistance. Although only 300 of the 1000 people in their community live on the few parts of Indigenous territory that were not taken by the cattle ranchers, 80% of the community has kept their language. It’s important to say this. While living outside of the community makes it all the more difficult to reproduce their culture, the community continues to resist.

In our work twenty years ago, I remember that young people who were teenagers participated. One of them is now a political science professor. He is also an advisor to the government. He clearly has the big picture, he knows he’s in a political arena and he knows its limitations, but he’s clear about what he has to say. I’m not saying that he is what he is because of what we did, of course not. But the fact that he witnessed the whole community coming together, where there were no confrontations, where an understanding and analysis of the issues came from community leaders themselves, I think that could have been very important for him. More than my presence or Alan’s or anyone else’s. That was in the case of Guatuso.

The case of Cabagra was very interesting because of the creation of a group called Shkikipa, which was an Indigenous adaptation of the justices of the peace that embodies traditional notions of community-based justice. Though they had an important land problem and cattle ranchers had taken much of their land, they realized that they were not going to achieve anything without strengthening themselves as a group first. The group began to resolve some cases among themselves and there was a real process of empowerment among them. These processes do not end. There is no end as long as there is interaction.

I had thought the group in Cabagra had stopped, but years later I had to return to Cabagra for a different situation. The judicial system is implementing what is called “peritaje cultural.” In English I think it’s called “cultural expertise.” In a case in which there are Indigenous people, the judge asks for certain clarifications because they know that there is a legal instrument that protects their customs.

I was asked to go back to Cabagra with cases involving lawsuits between Indigenous people over land. When I went there, I found that the Indigenous community had developed an institution that is not exactly that of Shkikipa, but that was influenced by everything that happened with Shkikipa and by some of its members in a community body that is called the constitutional law court. It’s a court that works with older and younger people, where they ask those who have problems among themselves to present their cases. They have a procedure that demonstrates what is happening in a certain issue or conflict. They issue a report, it is not a judgment, but an opinion. I had to go to the community and meet with them and corroborate the information in the report and then tell the judge what happened and that the court exists, it is serious, it is orderly and it is from the community. The people who are there are Indigenous and therefore it has total validity.

Very interesting processes were unleashed in Cabagra in the years after we left, because the community itself took up again very strongly its problems of organization and representation. There is an organization called Asociación de Desarrollo (Development Association) that represents the community before the state. At the time when I worked with Alan there, the organization had been taken over by the cattle ranchers. We had many conversations together about what had happened. Since that time, the community began the process of recovering their organization completely and reclaiming their land. Many had been involved in the conversations we had together earlier. Although I am not going to say that the lawsuits are over, the organization today is a totally legitimate organization, totally Indigenous. And that wasn’t even something that was planned. It’s something I found out not too long ago. I had to go and review all the minute books of the Development Association. I was able to gain a very precise idea of how the whole powerful process of taking back control of the organization happened. See Slide #3 for Marcos Guevara and Alan Levine with Colleagues Alí García Seguara and Ivelina Romagosa in Cabagra, 1993.

Putting the People First

One cannot be sure where things are going to end up, but I do believe that one can be sure of the importance of this process really working, not only with the people, but also putting the people before one’s own interests. When that is possible and it is facilitated, I think it is effective.

All cases are different. Each case has particularities, even in a country as small as this one. Obviously you can’t draw generalities, but I always think of a book by Fals Borda called “Knowledge and People’s Power,” because it establishes something fundamental, and for me it is true that knowledge is power. It is really true. And knowledge does not refer only to academic knowledge, but really to put in perspective the knowledge of all. And the knowledge of the people, about their issues, their lives, and about what is going on in their community. That is a very powerful force. The conditions of our society make it so that this knowledge isn’t expressed, or remains a bit hidden and dispersed. In the end, these processes of participatory action research facilitate how local knowledge and discussion generate knowledge in the people themselves, and I find that this is something fantastic.

KW: Yes, it’s something that has so much power. And those reflections could be important to share with others, because it’s not a project. We often think of projects as lasting two years and then coming to an end, but it’s true that the work continues and the community continues afterwards.

MG: I agree, I’d like to make it a goal to write about how the process has evolved in these past twenty years. I’ve been able to document some of the things that have developed, such as the Development Association, which is now completely Indigenous-led, and allows for the community to discuss and resolve their issues. Documenting that process is undoubtedly a task that I have.

KW: It’s so good to hear of how your vision and commitments impacted your work. What are the things that encourage you the most and frustrate you the most in relation to PAR?

How Change Happens

MG: Well, there is one thing, not that it’s a frustration, but let’s say it is something that one has to accept, and that is that sometimes I want changes to be made more quickly. Especially if you have a pretty clear idea of situations of injustice or discrimination and when there are clear laws in place. One would think that there should really be a very clear and fast change. And yet, it does not happen. You have to make yourself aware of how the process of time is for people and the implications that this has.

Processes have to take a certain rhythm. I believe that one can easily become desperate or make the mistake of thinking that one has to have an impact. That’s delicate for me because I have seen other people working on issues with very aggressive methodologies and at the beginning it may even seem to generate important impacts. But at the end of the day, they can end up generating a series of problems that make the situation more complicated.

For example, I was concerned when some of the groups coming from the outside who were focused on gender imposed a very patronizing vision of how things should change. And there have been experiences impacting Indigenous communities that have been disastrous. They (outsiders) try to impose changes on women, and this can provoke very strong divisions. So, that is where I feel that they have not taken the time, for example, to understand the processes as they really are. Instead, sometimes they come with very western preconceptions of what the gender situation is like, with little understanding, and they want to qualify everything at once according to that perspective. They don’t take the time to really understand gender issues in an Indigenous community and what an empowering change looks like.

Today, there are a series of very interesting thinkers that I have begun to read who are more radical, because they are the ones who say they are decolonial, like Espinosa Miñoso, I think they are fabulous. Recently these voices have begun to emerge and I feel that they propose elements for more accurate answers. They criticize those feminist groups that are extremely western and that only consider a single prism without understanding the factors of coloniality, and that is a mistake. It is important to understand the factors of coloniality and to integrate it into your work. That also implies a lot of patience in the sense that one is also learning. One cannot just come and pretend to be a teacher, but one also has to come with the attitude of a student and learn just like everyone else who comes. And well, that is very satisfying for you in the long run. But sometimes in the moments themselves it can seem hopeless in the sense that you are forced to be patient.

The Power of PAR: A Revolution of Consciousness

KW: Well, as a final question, what do you find most encouraging about this work?

MG: I feel that the work provokes a revolution of consciousness. That of everyone involved, including myself. Every time I can do something like this, I change my perspective of the world. I have a much clearer notion of people’s problems. At the same time, people also listen to each other, discuss with each other, build consensus and generate ideas for action. And although it is so difficult to achieve these changes, there is the reality, as in Cabagra, that one has to have patience and think that even if it seems like a grain of sand on a beach, somehow it is effective. On the other hand, in academic work, there are also reports and things that may seem very interesting and are going to be published in a very famous journal, and I have done that kind of publication, but sometimes I am left thinking, “will anyone really read that?”

Sometimes I think not, that it’s good for an encyclopedia and nothing else, and it doesn’t have an impact. But I do think that at the end of the day, PAR generates an impact and it generates an impact on myself and that is what I find fascinating. Once Fals Borda came here, it was interesting, as I had never seen him in person, I went to listen to him. He had been brought by the WFP, the World Food Program, to give a conference on participatory action research. It was at the end of the 90s, around there. So much time had passed that I thought: “the world had already changed so much, who knows who Fals Borda is now.” Will he still think the same way? Or what?

When I entered the room, I hadn’t even seen a picture of him, so I didn’t know what he looked like. I thought that maybe, after a while he would’ve become part of the establishment. That he may continue to have some impact, but not in the same way anymore.

And then, I was waiting and the room was full and I heard something happening in the back, and I just turned around and he was coming from the back to the front and he was waving. He was wearing an ordinary shirt, greeting each person saying, “Hello, I’m Orlando Fals Borda.” And then he explained a very interesting thing, which was his work on the Colombian constitution in ’91. A story that is not told almost anywhere that is very interesting about him. It was also so satisfying to think, and it has given me strength to think that, an intellectual of that magnitude can, in spite of everything that happens in this world, remain so faithful to his principles, even in political participation! Even though he is no longer doing participatory action research, that is, it still inspires him to guide change. And that is fabulous! So inspiring!

KW: Thank you so much for your participation!

This interview was transcribed, translated into English, and edited by PARCEO, January/February 2021.

Note. To read a full version of this interview, go to https://parceo.org/about/par/ and look for “An example of Par in Practice.”

To cite this work, please use the following reference:

Williams, K., Nevel, D., & Villalobos, C. (2021, February 15). Participatory Action Research in Action: An Interview with Marcos Guevara Berger. Social Publishers Foundation. https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/knowledge_base/participatory-action-research-in-action-an-interview-with-marcos-guevara-berger/

Copyrighted by Creative Commons BY-NC-SA

=========================================================================

Investigación Acción Participativa en Acción: Una entrevista con Marcos Guevara Berger

Resumen

Esta entrevista es con el antropólogo y educador Marcos Guevara Berger sobre su trabajo basado en Investigación Acción Participativa (IAP) con comunidades indígenas en Costa Rica. Su trabajo formó parte de un proyecto titulado “Una investigación legal y antropológica sobre los derechos de los pueblos indígenas en Costa Rica (en colaboración con Irìria Tsṍtchök, una organización de derechos indígenas) y con Alan Levine, un abogado de derechos civiles. La entrevista recalca las opiniones, reflexiones y experiencias de Marcos con IAP y con este proyecto. Guevara Berger comparte sus puntos de vista sobre la relación entre las ciencias sociales y el derecho; y entre la IAP, la universidad y la comunidad. La entrevista también comparte su puntos de vista sobre el papel del estado, el poder de la documentación, las limitaciones de un marco legal, preguntas sobre cuyas voces y experiencias son reconocidas, la resistencia comunitaria, cómo tener un impacto, y cómo ocurre el cambio. Esta entrevista es la voz y la sabiduría de un tremendo ser humano y educador.

Información de Contexto

Marcos Guevara Berger[iii] (1958-2021), antropólogo respetado, educador e investigador, fue un querido amigo, mentor y una gran inspiración para PARCEO[iv] y para muchos de los miembros de nuestro equipo que tuvieron la oportunidad, no sólo de escuchar sus palabras, sino de ver su trabajo basado en IAP en acción. Marcos trabajó durante muchos años con las comunidades indígenas de Costa Rica. Su trabajo y su forma de vida fueron el fiel reflejo de sus principios y su compromiso con la justicia social y con la necesidad de que todas las personas sean tratadas con el respeto y la dignidad que se merecen. Se le echará mucho de menos, pero sabemos que su esencia y el impacto de su sabiduría nos acompañarán siempre.

La entrevista con Marcos a continuación fue realizada por Krysta Williams el 26 de febrero de 2016, en español, en la casa de Marcos en Costa Rica. La entrevista fue traducida al inglés por Chloe Villalobos y editada para su claridad por el equipo de PARCEO.

Un informe para la Fundación MacArthur, “A Legal and Anthropological Inquiry into the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Costa Rica” (Una investigación legal y antropológica sobre los derechos de los pueblos indígenas en Costa Rica), que describe un proyecto de IAP realizado por el profesor Marcos Guevara y el abogado de derechos civiles, Alan Levine, en dos comunidades indígenas.

Investigación Acción Participativa en Acción: Una Entrevista con Marcos Guevara Berger

En la entrevista, “KW” se refiere a Krysta William, la entrevistadora, y “MG” se refiere a Marcos Guevara, el entrevistado.

Sobre Investigación Acción Participativa (IAP)

KW: He leído el informe que escribió con Alan sobre su proyecto, entonces tengo un poco de conocimiento de todo ese trabajo. ¿Si pudieras empezar por describir su trabajo, su conexión con IPA y la relación entre IAP y sus clases en la universidad?

MG: Bueno. Para mí la orientación de hacer un trabajo con investigación participativa – PAR es “IAP” en español: Investigación Acción Participativa – es obviamente siempre una ocasión muy importante por dos razones. Primero porque siento una identificación muy fuerte con esta metodología. Siento que es una metodología más justa en el sentido que no antepone los intereses del investigador o del académico, sino que realmente parte de las propuestas de las comunidades. Y entonces el investigador se integra al proceso cómo una persona más, con un rol un poco de facilitador, pero no como él que guía todo el proceso. Facilita algunas cosas y puede intervenir en otras, pero pone mucho peso en la interacción de las personas.

No es fácil hacer esto en el mundo académico no es fácil. Es decir, el mundo académico parece estar lejos de esto y de hecho entonces no es casi nunca posible, por ejemplo, en el espacio de un curso no puedo hacerlo. La investigación acción participativa no establece un plazo. Es decir, uno empieza procesos y eso no tiene necesariamente un fin determinado. No es algo que se pueda programar en el marco de un curso. Uno puede leer artículos sobre PAR y discutirlo, de hecho lo hago en mis clases, pero las ocasiones para poder hacerlo realmente son muy pocas. No es algo que desconociera, porque el mismo Orlando Fals Borda — alguien que hace un trabajo de IAP que admiro mucho — él mismo, en alguna parte, explica que él era profesor de sociología en la Universidad Nacional de Colombia, y cuando él empezó a trabajar con eso tuvo que irse de la universidad porque no había espacio para IAP. Entonces desarrolló su experiencia haciendo esto y, en una conferencia que escuché, decía que fueron sus alumnos que luego fueron profesores de la universidad que lo llamaron para que viniera a hablara de IAP en la universidad. Pero nunca se integró realmente en el mundo académico.

Es lamentablemente un problema porque lo académico se establece en función de unos parámetros de competitividad profesional, que muchas veces pone el peso en un conocimiento adquirido y certificado en un diploma y se aleja de la idea que el conocimiento no necesariamente está en un libro, pero que, de manera significante, puede estar en la experiencia.

Celebro cada vez que puedo trabajar con IAP porque es muy importante para mí. Me realiza mi persona, me satisface mucho más qué otras cosas que tengo que hacer y que estén muy alejadas de eso. Para realizar un proceso de investigación acción participativa uno nunca está seguro del resultado. Es decir, si la decisión la toma un colectivo de personas y no un investigador, nunca va a estar seguro realmente qué es lo que va a salir. Entonces por esa razón a menudo no logra encajar muy bien con el mundo académico.

Irìria Tsṍtchök, Una Organización Liderada por Personas Indígenas en Costa Rica

KW: Pensando en el proyecto en el que usted y Alan trabajaron juntos hace ya más de 20 años, sé que lo hicieron a través de la organización dirigida por personas indígenas, la Fundación Irìria Tsṍtchök, de la que usted formaba parte. ¿Sigue existiendo la Fundación?

MG: No. He pensado mucho sobre eso porque yo mismo estuve bastante involucrado en la creación de la fundación, aunque no como miembro fundador, pero sí como impulsor de la idea. Porque la fundación se creó en un momento cuando hubo un rechazo del Estado para seguir trabajando un enfoque de parques nacionales y áreas protegidas con comunidades indígenas y campesinas. A pesar de la voluntad inicial del Estado de realizar un proceso participativo con las comunidades indígenas y campesinas, más tarde retiró sus esfuerzos debido a sus ideales conservadores. En ese momento, las comunidades vieron la necesidad de crear la Fundación Irìria Tsṍtchök, para continuar el trabajo que el Estado había abandonado.

Irìria Tsṍtchök la fundaron líderes indígenas y campesinos alrededor de lo que era el Parque de la Amistad, que era un área en la que estábamos trabajando. Se creó con objetivos específicos que se cumplieron. Creo que la fundación cumplió metas que fueron importantes: financiar las comunidades y fortalecer su visión de los derechos que tenían sobre esas áreas territoriales que estaban protegidas. Y eso fue fundamental yo creo, y sigue pesando. La fundación consiguió el objetivo de consolidar las poblaciones ante el reclamo de sus derechos. Entonces no es tan sencillo para el gobierno decir que no van a tomar en cuenta estas poblaciones y comunidades. Refierese a la diapositiva #2 para Marcos Guevara Berger y Alan Levine en acción, 1993.

El Comienzo del Proyecto: Ciencias Sociales y Derecho

KW: ¿Puede hablar un poquito del comienzo de su proyecto y colaboración?

MG: Cuando Alan y yo nos reunimos para preparar nuestro enfoque de IAP, nos complementamos mucho como antropólogo y abogado de derechos civiles. IAP es un enfoque de ciencias sociales y no de derecho. Al mismo tiempo, era importante tener conocimientos sobre cómo reivindicar los derechos desde una perspectiva jurídica. Desde el punto de vista de derecho, es muy raro realmente gente involucrarse en proceso de investigación acción participativa. Es contrario a la metodología tradicional de derecho. Sin embargo, fue muy importante esa participación de Alan como abogado. Por dos razones: primero porque hizo de lo jurídico algo verdaderamente palpable y no apenas unas normas. Pero por otro lado también, y esa fue tal vez la parte que yo aprendí más, fue en el sentido de entender que el sistema legislativo como tal no va a resolver las cosas. Era una visión un poco ingenua que yo tenía. Que, si logramos un buen caso, bien justificado, bien armado, realmente vamos a ganar algo y la comunidad va a ganar. Y realmente no fue así.

Trabajando con Dos Comunidades: Cabagra y Guatuso

Pensamos trabajar con dos comunidades con contextos diferentes y también con condiciones muy distintas: Cabagra y Guatuso, que describiré en un momento. El trabajo de Guatuso estaba más orientado a lo jurídico y el de Cabagra implicaba más una cuestión de organización interna. Inicialmente, pensé que el enfoque jurídico de Guatuso iba a tener un mayor impacto en los derechos de la comunidad. Veinte años después, veo cómo los resultados de Cabagra, que tenían más que ver con la organización interna, tuvieron un impacto muy crítico.

En Cabagra, ya había trabajado con la comunidad antes que Alan y yo empezaramos nuestro trabajo. Así que, a partir de esta experiencia y de las relaciones que construí, pensé que Cabagra sería un buen lugar para hacer un proceso de IAP. No sería como alguien de fuera que acaba de venir a proponer algo. La comunidad sabía que no se trataba de imponer una idea, sino de generar algo que consideraran beneficioso para ellos.

En la comunidad de Guatuso, aunque nunca había trabajado allí, conocía a un par de personas y sabía que había un problema de tierras muy fuerte. Es una comunidad pequeña, pero en la cual el 90% fue tomada por extranjeros. Ha provocado una situación muy compleja. Los Malekus son pocas personas, son 1000 personas. Y la gran mayoría no viven en su comunidad. Tienen que salir y trabajar como empleadas o en las bananeras. Entonces tienen una situación dramática, por eso de la tierra. Y habían protagonizado unos años antes una toma de tierras. Un grupo organizado de la comunidad invadieron una finca que estaba dentro del territorio indígena pero que la habían tomado unos ganaderos. Entonces esa experiencia, de la cual yo tenía conocimiento, me pareció Interesante como un elemento para decir: aquí en esta comunidad realmente hay gente que sabe lo que quiere. Está decidida, aquí en español decimos “de armas tomar”. Entonces nos acercamos a la comunidad en Guatuso y nos señalaron que “lo nuestro es tierras, es crítico y tenemos que entender mejor cómo es esto de los derechos territoriales.” Les dijimos que estábamos interesados en trabajar juntos para apoyarlos en su reivindicación de sus derechos.

Definiendo el Enfoque de la Comunidad

Inicialmente, decidimos trabajar con la reclamación de tierras en Guatuso, y organización comunitaria en Cabagra. Durante nuestras conversaciones juntos, la comunidad nos señaló lo que les interesaba, que podrían aprovechar, y qué enfoque querían tomar. Ese proceso tomó varias reuniones. No hay un tiempo plazo para definir eso. Concordamos que la comunidad podía seguir trabajando a su propio ritmo. Nosotros los visitamos cada 15 días en cada comunidad para ver como iba la discusión, que proponían hacer, y si había algo que nosotros deberíamos aportar. Entonces, así fue que tal vez en la segunda o tercera reunión de la comunidad que más o menos se había definido un tema.

Nuestro rol fue ayudar a facilitar la conversación y hacer un seguimiento de lo que se discutió en cada reunión. Usamos, por ejemplo, una cámara de video, entonces al final de cada taller preguntabamos “¿Quién quiere hacer un resumen de lo que hicimos hoy?” Alguna persona se proponia en su propio idioma, y logramos decir que discutimos esto, llegamos a tales acuerdos y la próxima vez vamos seguir por aquí. Esto fue importante porque había gente que siempre llegaba, pero muchas veces había gente que no pudo llegar a una reunión, o había gente nueva que venía, entonces como para que no estuvieran perdidos tratábamos de empezar la reunión proyectando un poco el video. Para que vieran en qué quedamos.

En Guatuso, estábamos explorando el posible impacto de las disposiciones de los tratados internacionales relativas a los derechos de los pueblos indígenas. Sabíamos que la legislación nacional ha sido, y sigue siendo, bastante ineficaz para resolver las reclamaciones de tierras. Pero las disposiciones de los tratados internacionales, en nuestro sistema jurídico, tienen superioridad de fuerza con respecto a la ley. Y las reclamaciones por violación de esas disposiciones pueden presentarse directamente ante el Tribunal Constitucional. Pensamos que la gente podría estar interesada si comprendiera que no tendría que perder el tiempo en los tribunales locales, donde nunca ha tenido éxito, y que podría hacer su reclamación en el Tribunal Constitucional, que es superior a esos tribunales locales.

En Guatuso tuvimos que emprender un proceso más informativo al principio. Por ejemplo, discutir juntos la diferencia entre un tratado de derechos humanos y la legislación nacional. Nos dieron tareas. Trabajamos en ello hasta que se desencadenó un debate sobre lo que realmente podían hacer. Había muchos puntos de vista diferentes, y tratamos de ayudar a generar un clima en el que personas con puntos de vista muy diferentes pudieran escucharse mutuamente y expresar sus opiniones.

Sacar a la Luz Documentación y Negligencia de Estado

Una de las cosas en las que trabajamos con la gente de Guatuso fue que, aunque la falta de actuación del Estado ante las reclamaciones de tierras indígenas no era nada de nuevo, la comunidad necesitaba demostrar que habían estado haciendo tal reclamación durante mucho tiempo. Así que juntaron hechos, por ejemplo, nos dijeron que fueron entrevistados por el periódico de la universidad. Con esta información, y la fecha de la entrevista, pudimos buscar y logramos encontrar un artículo en el periódico que decía que habían hecho tal denuncia. Luego ellos habían conservado cartas en las cuales denunciaban al Estado. Entonces, pudimos juntar nuestras competencias. Nosotros podíamos buscar los archivos de las bibliotecas, o periódicos, y ellos buscaban en sus casas sus cartas y eso. Así logramos reunir un cuerpo de información interesante que mostraba que ellos, desde la creación del territorio indígena, constantemente fueron reclamar ante el Estado y decir “eso está pasando, esto es lo que dice la ley, y ustedes no están haciendo lo que deben hacer.”

Lograron demostrar realmente que el Estado había sido omiso aplicando la ley. Y eso el Tribunal Constitucional lo reconoció. Ese caso ahí lo ganó la comunidad, Cuando eso venía saliendo inicialmente, realmente parecía que iba a ser algo muy importante. No solo para el caso de Guatuso, sino que diciendo, bueno, es una sentencia del Tribunal Constitucional y eso puede tener un valor universal para todos los demás casos. Osea, en cualquier manera que otra comunidad pueda demostrar que el Estado fue omiso aplicando la ley, puede usar la misma jurisprudencia. Sin embargo, lo interesante es que el caso legal de de Guatuso no evolucionó tanto como yo pensé.

El Sistema Legislativo

MG: Ahí es donde yo digo que fue la parte donde yo aprendí más de Alan, porque mi perspectiva de cómo funcionaba el sistema jurídico fue un poco ingenua. Pensando que simplemente demostrando un derecho era lo suficiente. Pero después de eso vienen un montón de acciones, que implica abogados, implica pleitos, osea no termina. El estado, dentro de la escena del mundo capitalista, no fácilmente va a ceder ante los derechos que reclama la comunidad. Sino que va siempre a defenderse, y eso es efectivamente lo que pasó. Entonces por más que había una sentencia favorable, después venía lo que se llama la ejecución de la sentencia, que requería abogados y otros procesos legales, los cuales no se pudieron llevar a cabo porque la comunidad no tenía la capacidad suficiente para hacer esa parte sin acompañamiento de un profesional. El caso de la sala constitucional fue diferente porque en la sala no se requiere un abogado. La sala constitucional cuando se creó para reclamar derechos establecidos en la constitución, determinó que cualquier formato es suficiente. Hay un caso muy famoso aquí de un niño que limpiaba zapatos, un niño de 10 años, que en una servilleta escribió su caso y como pensaba que estaban violentando sus derechos y lo presentó y lo ganó.Eso es realmente interesante porque no se necesitó ningún abogado. Sin embargo, lo que viene después es donde se pone difícil.

El Estado tiene un órgano para defenderse, la procuraduría. Por eso, si una comunidad no tiene un buen abogado, se hace realmente difícil crear el cambio legal que se quiere. Aprendí que en casos como este, es necesario pensar a largo plazo. Por ejemplo, cuando Alan y yo trabajábamos en la comunidad, no había abogados indígenas. Llevar el caso con un abogado externo podría, potencialmente, causar más daño y ser un desempoderamiento. Hoy en día hay algunos, incluso hay uno en Guatuso, y eso es muy empoderador para la comunidad.

El Trabajo Continúa y Está Interconectado

KW: Tengo una pregunta rápida, desde su punto de vista, ¿qué diría sobre el proceso que se inició mirándolo ahora?

MG: Bueno, fue muy positivo en la visión que la comunidad tiene conocimiento de sus derechos y la capacidad de demostrarlo. Esa parte sí es ciertamente una ganancia y ha tenido un impacto en la comunidad. Pero por otro lado tengo que reconocer que ni siquiera yo mismo tenía clara la idea de cómo iba a terminar. Entonces, claro, es un poco el riesgo por decirlo de alguna manera. Bueno no es un riesgo exactamente, porque no se perdió nada. Pero si es un riesgo en el sentido de no saber cómo va a acabar.

KW: ¿Y hay alguna manera para no desanimar a la gente en ese proceso? Porque muchas veces estás trabajando bien duro en algo, pero llega a un punto donde no está solucionado.

MG: Bueno, tal vez es importante recordar que este trabajo que hicimos es apenas un pequeño enfoque entre miles de causas y trabajo que se está haciendo. La solución de todo lo demás no depende solo de esto. Quiero decir que hay otras luchas y otros frentes de lucha que también han estado presente y en que no necesariamente yo he estado presente, pero que estaban ahí. Y muchos han logrado tener alguna clase de incidencia. Pero todo está interconectado. Por ejemplo, la producción cultural de la comunidad de Guatuso está centrada en el uso de los recursos de los ríos y el bosque. Incluso su vida ceremonial se desarrolla alrededor del río. Con el problema de tierras, se robó su acceso a los sitios tradicionales que usaban. Pero la comunidad no renunció y siguió resistiendo. No fue apenas una lucha legal, sino que también fue una lucha política y arraigada en la comunidad.

La Resistencia Comunitaria Continúa

Y han ganado algunos otros casos. Por ejemplo, hace 3-4 años, una persona fue a pescar en un río que no estaba en el territorio, pero estaba asociado a un refugio de vida silvestre. Llegó la policía y lo detuvo. Ahí empezó un caso legal porque lo persiguieron por un delito que se llama “ofensa a los recursos naturales.” Después se demostró que realmente el estilo de vida tradicional de los Malekus es ese. Entonces, con la existencia de un convenio internacional que anteponía la costumbre ante la ley, el Estado tenía que ceder. En ese caso, demostrando realmente que ese uso del río corresponde a una costumbre ancestral, la ley penal no tenía efecto.

Creo que es importante seguir trabajando por los derechos humanos y demostrar que no debemos abandonar la lucha por los derechos. Ese principio, definido por la comunidad, es muy importante. Siento que esto ha fortalecido a la comunidad porque todos tienen causas comunes. Para mí, los Malekus reflejan la resistencia. Aunque sólo 300 de las 1.000 personas de su comunidad viven en las pocas partes del territorio indígena que no fueron tomadas por los ganaderos, el 80% de la comunidad ha mantenido su lengua. Es importante decir esto. Aunque el hecho de vivir fuera de la comunidad hace más difícil la reproducción de su cultura, la comunidad sigue resistiendo.

En nuestro trabajo hace 20 años, recuerdo que participaron jóvenes que eran adolescentes, uno de ellos ahora es profesor en ciencias políticas y es asesor del gobierno. Tiene claramente el panorama, sabe que está en un ámbito político y sabe que eso tiene limitaciones, pero tiene claro lo que tiene que decir. Pienso, no digo fue gracias a lo que nosotros hicimos, claro que no.

El hecho de que fuera testigo de las reuniones de la comunidad, en las que no había enfrentamientos, en las que la comprensión y el análisis de los problemas provenían de los propios líderes de la comunidad, creo que pudo ser muy importante para él. Más que mi presencia o la de Alan o la de cualquiera. Eso fue en el caso de Guatuso.

El caso de Cabagra fue muy interesante por la creación de un grupo llamado Shkë́kipa, que era una adaptación indígena de los juzgados que refleja las nociones tradicionales de justicia comunitaria. Aunque tenían un importante problema de tierras y los ganaderos les habían arrebatado gran parte de ellas, decidieron que no iban a conseguir nada sin consolidarse primero. El grupo empezó a resolver algunos casos entre ellos y se produjo un verdadero proceso de empoderamiento. Estos procesos no se acaban. No hay final mientras haya interacción.

Después pensé que el grupo de Cabagra se había perdido, que había funcionado un tiempo y ya no. Pero años más tarde me tocó volver a Cabagra con una situación diferente. En el sistema jurídico se está implementando lo que llaman el peritaje cultural. En un caso donde hay personas indígenas, el juez pide ciertas aclaraciones porque saben que hay un instrumento legal que protege las costumbres.

Me han pedido que volviera a Cabagra con casos de pleitos entre personas indígenas por la tierra. Cuando fui allí, me encontré con que la comunidad indígena había desarrollado una institución que no es exactamente la de Shkë́kipa, pero que estaba influenciada por todo lo que ocurrió con Shkë́kipa y por algunos de sus miembros en un órgano comunitario que se llama Tribunal de Derecho Constitucional. Es un tribunal que trabaja con personas mayores y jóvenes, donde piden a los que tienen problemas entre ellos que presenten sus casos. Tienen un procedimiento que demuestra los diferentes lados de un determinado asunto o conflicto. Emiten un informe, no es un juicio, sino una opinión. Tuve que ir a la comunidad y reunirme con ellos y corroborar la información del informe. Tuve que decirle al juez lo que pasó y que el tribunal existe, es serio, está ordenado y es de la comunidad. Las personas que están ahí son indígenas y por lo tanto tiene total validez.

En Cabagra se desencadenaron procesos muy interesantes en los años posteriores a nuestra salida, porque la propia comunidad retomó con mucha fuerza sus problemas de organización y representación. Hay una organización llamada Asociación de Desarrollo que representa a la comunidad ante el Estado. En la época en que trabajé con Alan allí, la organización había sido tomada por los ganaderos. Tuvimos muchas conversaciones juntos sobre lo que había pasado. Desde entonces, la comunidad comenzó el proceso de recuperar su organización por completo y reclamar sus tierras. Muchos habían participado en las conversaciones que mantuvimos juntos anteriormente. Aunque no voy a decir que los pleitos han terminado, la organización es hoy una organización totalmente legítima, totalmente indígena. Y eso no era algo que estuviera planeado. Es algo que descubrí hace poco tiempo. Tuve que ir a revisar todos los libros de actas de la Asociación de Desarrollo. Pude hacerme una idea muy precisa de cómo ocurrió todo el proceso de retomar el control de la organización, que fue muy poderoso. Refierese a la diapositiva #3 para Marcos Guevara y Alan Levine con colegas Alí García Seguara y Ivelina Romagosa en Cabagra, 1993.

Priorizando a las Personas Primero

Todos los casos son distintos. Cada caso tiene particularidades, incluso en un país tan pequeño como este. Evidentemente no se pueden sacar generalidades. Pero si pienso siempre en un libro de Fals Borda que se llama “Conocimiento y Poder”, porque el primero establece algo fundamental y para mi está cierto que el conocimiento es poder. Realmente es cierto. Y el conocimiento no se refiere sólo al conocimiento académico, sino realmente poner en perspectiva el conocimiento de todos. Y el conocimiento de la gente, sobre sus problemas, sus cosas, y sobre lo que está pasando en sus comunidades. Eso tiene una fuerza muy grande. Las condiciones hacen que ese conocimiento no logre expresarse, o quede un poco escondido, disperso. Y en el fondo estos procesos de investigación acción participativa, lo que facilitan es como dar capacidades de esos conocimientos locales o de las discusiones que puede generar esos conocimientos en las mismas personas, y eso yo encuentro que es algo fabuloso.

KW: Sí, es algo que tiene tanto poder. Y puede ser una reflexión para los demás y para compartir porque no es un proyecto, que muchas veces pensamos en proyectos que duran dos años y termina, pero es verdad que el trabajo sigue y la comunidad sigue después.

MG: Estoy de acuerdo, me gustaría que mi objetivo fuera escribir sobre cómo ha evolucionado el proceso en estos últimos veinte años. He podido documentar algunas de las cosas que se han desarrollado, como la Asociación de Desarrollo, que ahora está completamente dirigida por los indígenas, y permite que la comunidad discuta y resuelva sus problemas. Documentar ese proceso es sin duda una tarea que tengo.

KW: Es tan bueno escucharle y saber cómo sus visiones impactan su trabajo. Bueno, ¿cuáles son las cosas que le animan más y que le frustran más en relación a IAP?

Cómo Ocurren los Cambios Sociales

MG: Bueno, hay una cosa, no es que sea una frustración, pero digamos que es algo que uno tiene que aceptar, y es que uno a veces quiero o pensaría que hay cambios que se deberían hacer más rápido. Especialmente si se tiene una idea bastante clara de situaciones de injusticia o de discriminación y cuando hay leyes muy claras. Uno pensaría que debería realmente haber un cambio muy claro, muy rápido. Y sin embargo no ocurre. Sino que tiene que hacer uno mismo conciencia de cómo es el proceso del tiempo para la gente y las implicaciones que esto tiene.

Los procesos tienen que llevar un cierto ritmo. Creo que uno puede desesperarse fácilmente o cometer el error de pensar que tiene que tener un impacto. Eso es delicado para mí porque he visto a otras personas trabajar en estas cosas con metodologías muy agresivas y al principio puede parecer que incluso se generan impactos importantes. Pero al final pueden terminar generando una serie de problemas que complican la situación.

Por ejemplo, me preocupaba cuando algunos de los grupos centrados en cuestiones de género que venían de fuera tenían una visión muy paternalista de cómo debían cambiar las cosas. Y ha habido experiencias que han afectado a las comunidades indígenas que han sido desastrosas. Los grupos de fuera tratan de imponer los cambios a las mujeres, y eso puede provocar divisiones muy fuertes. Entonces, ahí es donde siento que no se han tomado el tiempo, por ejemplo, de entender los procesos como realmente son. En cambio, a veces vienen con prejuicios muy occidentales de cómo es la situación de género, con poca comprensión, y quieren calificar todo de una vez según esa perspectiva. No se toman el tiempo necesario para entender realmente la discriminación de género en una comunidad indígena y cómo es un cambio de empoderamiento.

Ahora hay una serie de doctoras muy interesantes que he empezado a leer que son más radicales, porque son las que se dicen decoloniales, como Espinosa Miñoso, me parecen fabulosos. Hace poco han empezado a salir esas voces y siento que en lo que ellas plantean elementos para respuestas más certeras. Porque ellas critican a esos grupos feministas que son sumamente occidental y que solo consideran un solo prisma sin entender los factores de la colonialidad, y eso es un error. Es importante entender los factores de colonialidad e integrarlo. Eso implica también mucha paciencia en el sentido de que uno también está aprendiendo. Uno no puede llegar y pretender ser simplemente un maestro, sino que también tiene que llegar con una actitud de estudiante. Y aprender igual que todos los que vienen. Y bueno, eso a la larga es muy satisfactorio para uno. Pero a veces en los momentos mismos puede parecer desesperante en el sentido de obligarse a ser pacientes.

El Ooder de IAP: Una Revolución de Conciencia

KW: Bueno, para terminar, ¿qué es lo que anima más en este trabajo?

MG: Siento que este tipo de trabajo provoca una revolución de la consciencia. Y la de todos los participantes, incluso la mía. Cada vez que se puede hacer algo así, yo cambio mi perspectiva del mundo. Tengo una noción mucho más clara de los problemas de la gente. Al mismo tiempo, la gente también se escucha, discute entre sí, crea consensos y genera ideas de acción. Y aunque sea tan difícil lograr esos cambios, hay como en Cabagra, que uno tiene que tener la paciencia y pensar que, aunque parezca un granito de arena en una playa, de alguna manera tiene efectividad. Muchas veces en cambio, el trabajo académico, también hay informes y cosas que pueden parecer muy interesantes y van a ser publicadas en una revista muy famosa y bueno. Yo he hecho ese tipo de publicaciones, pero a veces me quedo pensando, “¿alguien de verdad leerá eso?”

A veces pienso que no, que eso sirve como para una enciclopedia y nada más. Y no tiene un impacto. Entonces, si pienso que al fin y al cabo genera un impacto y genera un impacto en mí mismo y eso es lo que me parece fascinante. Una vez Fals Borda vino aquí, fue interesante, como yo nunca lo había visto en persona, lo fui a escuchar. Lo había traído la FAO, organización mundial de alimentos. A hacer una conferencia sobre investigaciones participativas. Fue a finales de los años 90 por ahí. Ya había pasado tanto tiempo que pensé que ya el mundo había cambiado tanto, ¿quien sabe quien és Fals Borda ahora? (se ríe) Entonces, ¿seguirá pensando igual? ¿O que?

Yo cuando entre en el salón, ni siquiera había visto una foto de él, entonces no sabía cómo era. Pensé que, al cabo del tiempo, fuera posible que se hubiera hecho parte del establishment. Que tal vez puede seguir teniendo algún impacto, pero de la misma manera ya no. Y después, mientras esperaba, sentí que algo pasaba detrás mía, y me volteé y le vi viniendo de detrás saludando a todos. Venía con una camisa corriente saludando a cada persona diciendo “hola, soy Orlando Fals Borda.” Después explicó una cosa muy interesante que fue su intervención en la constitución de Colombia en el año 91. Es una historia que no está relatada en casi ninguna parte que es muy interesante de él. También fue tan satisfactorio pensar, y me ha dado fuerza de pensar, que si un intelectual de esa magnitud puede, a pesar de todo lo que pasa en este mundo, seguir tan fiel a sus principios, incluso en una participación política! Aunque ya no está haciendo investigación acción participativa, es decir, eso lo sigue inspirando a orientar el cambio. ¡Eso es fabuloso! ¡Mucha inspiración!

KW: ¡Muchas gracias por su participación!

Esta entrevista fue transcrita, traducida al inglés y editada por PARCEO, Enero/Febrero 2021.

Note/Nota.

[i] Marcos Guevara Berger, University of Costa Rica (UCR), San José, Costa Rica; Doctor in Ethnology from the University of Paris X, Nanterre, France; Academic at the School of Anthropology, University of Costa Rica (UCR), San José, Costa Rica.

[ii] PARCEO, a resource and education center, is rooted in a Participatory Action Research (PAR) framework, which builds upon a community’s knowledge, wisdom, and expertise toward sustained community strength and meaningful social change.

[iii] Marcos Guevara Berger, Universidad de Costa Rica (UCR), San José, Costa Rica, Doctor en Etnología de la Universidad de Paris X, Nanterre, Francia; Académico en la Escuela de Antropología (UCR), San José, Costa Rica.

[iv] PARCEO, un centro de recursos y educación, está basado en la Investigación Acción Participativa (IAP), que aprovecha los conocimientos, la sabiduría y la experiencia de la comunidad para lograr el empoderamiento comunitario y un cambio social significativo.

Para cide este trabajo, utilice por favor la referencia siguiente:

Williams, K., Nevel, D., & Villalobos, C. (2021, February 15). Investigación Acción Participativa en Acción: Una entrevista con Marcos Guevara Berger. Social Publishers Foundation. https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/knowledge_base/participatory-action-research-in-action-an-interview-with-marcos-guevara-berger/