Summary

This essay shares my passion for, and belief in, principles of Participatory Action Research (PAR) as an approach that can help strengthen and deepen our work for justice. I share some of what I learned experiencing PAR in practice beginning from the time I spent in Costa Rica working with the late Marcos Guevara. They were profound lessons that I carry with me in my work and life until this very day.

Context

As I have been thinking so much about the moment we are in – the extent of injustice manifested in so many ways across the globe – I also think about the powerful organizing taking place, and I believe that PAR offers a framework for meaningful and sustained long term work and organizing for justice. I find its possibilities so inspiring.

Organizing for Justice: The Power of Participatory Action Research

Introduction

At this moment, when so much is precarious for so many – from the day-to-day and long-term impact of a global pandemic and climate destruction to the devastating impacts of capitalism, white supremacy, misogyny and transphobia, and more – I have been paying special attention to, and learning so much from, the ways that people and groups are organizing, resisting, building community, and caring for one another. I have been thinking more about what offers strength and sustenance in our work for justice at this moment, and which principles and frameworks help ground our work and shape how we meaningfully enter and participate in struggles for social transformation.

I have always been a big believer in the power of learning by example. I first believed that because my parents, throughout my childhood and until their deaths, didn’t just encourage us to pursue justice and to treat people with generosity and respect, but I never saw them act any other way. The people who have impacted my thinking and my behavior the most have always been those whose words and actions seemed seamlessly connected.

This essay honors my parents’ legacies; it is born of both deep concern with the growing precarious realities for so many across the globe and an abiding belief in the power of learning from and with one another, building community together, and rooting ourselves in a commitment, in word and action, to pursuing justice. As I reflected upon all that I learned from seeing my parents living their lives, I found myself deeply drawn to principles embedded in Participatory Action Research (PAR), particularly as I witnessed and experienced it in practice.

Marcos Guevara: Embodying Principles of Participatory Action Research (PAR)[1]

I spent time with a remarkable person, Marcos Guevara, when I lived in Costa Rica many years ago, who was the embodiment for me of how, with soul and genuineness, to organize and work in community. An anthropologist who was part of an organization, Iriria Tsochok[2] , led by members of the Indigenous community in Talamanca, Costa Rica, Marcos embraced the principles of Participatory Action Research (PAR) that have been at the heart of my work, and even of my life, since then. Before meeting Marcos, I had read about PAR (and popular education) but had never actually experienced it in real time.

Marcos, who heartbreakingly died from COVID-related complications in January, 2021, helped me understand that PAR wasn’t just a methodology to study and use, but at its core, it required honoring community and a people’s deep wisdom, knowledge, and expertise. He did that in every encounter I saw him have. I had the great privilege to work for some time together with Marcos and Iriria Tsochok and to experience first-hand the ways that principles of PAR were interwoven in all they did. Marcos also had a profound impact on our work at PARCEO, the PAR-based center based in the U.S. that I am part of. PARCEO partners with community groups, universities, and other institutions – locally, nationally, and globally – seeking to deepen their community education, organizing, research, and cultural work; form principled collaborations; and develop new initiatives rooted in principles of justice.

Experiences with Participatory Action Research

I have always related to PAR as a framework, an approach that values and honors the experience, knowledge, and leadership of those most impacted by injustice as we collectively work for transformative change. While I have benefited greatly from all that I have read about PAR, what I write here is more about what I have experienced and learned from experiencing PAR in action. I was particularly motivated to share these experiences now because they – and all I have learned – feel so relevant to the moment we are in.

I learned from Marcos’s example that PAR is about seeking justice and how we can do that most meaningfully and with as much integrity as possible. PAR is also a pedagogy that underscores the fundamentally important consideration about who is in the room – from the beginning – not superficially, but deeply. It is about challenging the notion of who has the expertise and how we think about what expertise is and how knowledge is created and shared. In a PAR-generated process, what emerges can look many different ways depending on what the group/community determines together. We are all teachers and learners. The process is rooted in building knowledge together to understand and participate in creating the change we seek.

PAR has been central to social movements across the globe engaged in transformative processes for liberation and has a long history in the Global South. Among those who helped shape PAR early on, Colombian sociologist and political activist Orlando Fals Borda (Gott, 2008; Rappaport, 2020) is widely recognized as one of its founders and inspirations. PAR also has been closely aligned with popular education and the liberatory, critical pedagogy of Brazilian educator, scholar, and cultural worker, Paulo Freire (1970/2007). Many have built on the work of Fals Borda and Freire and have shared their own experiences of the power of PAR. For example, in Education, Participatory Action Research, and Social Change: International Perspectives, edited by Dip Kapoor and Steven Jordan (2009), the chapter authors, coming largely from Indigenous communities and the Global South, are deeply committed to supporting participation in community-generated processes that foster liberation and self-determination and opposing neo-liberal appropriation and intellectual imperialism.

Embracing PAR Principles in Our Work for Justice

Some of the principles of PAR that I experienced being enacted in Marcos’ life and work – and that, since then, have been central to my work and to our work at PARCEO – include reflecting deeply upon:

- the power and beauty of our stories, our histories (both individual and collective);

- how we enter new spaces – especially challenging “insider/outsider” and “us/them” binaries;

- whose voices are valued and centered – and whose aren’t;

- when (and how) silences reify power and when (and how) they can open up space for deep reflection and for honoring different types of learning and organizing;

- how to gauge “success” in our work – who makes that determination and (why) it matters;

- what it means to be a principled, intentional, and genuine partner;

- how we envision community(ies) and who is part of our community/ies;

- (I am intentionally repeating this) the power and beauty of our stories, our histories (both individual and collective);

- the power of collective reflection, imagining, envisioning, and deep community education; and

- challenging notions of “expertise” and recognizing how we are experts in our own lives.

My Personal PAR Experience with Work for Justice: Examples

One of the PAR initiatives I was part of well-illustrates these principles in action. The Center for Immigrant Families (CIF) was a community-based organization of mostly low income immigrants, primarily women of color, and other community members in uptown Manhattan (1998-2008). CIF had a deep commitment to creating collective spaces grounded in members’ social, political, emotional, and economic needs and realities. CIF built a range of community programs, women’s healing circles, organizing, and community-building, and worked in coalition with racial justice groups across New York City (NYC). Rooted in a popular education and PAR framework, CIF believed in the transformative power of storytelling, and central to CIF’s programs was the sharing of stories, particularly migration stories. It was a powerful process of communal storytelling. The sharing of the stories not only laid the foundation for an unfolding process of organizing for change, but the stories themselves were often liberating and empowering.

Many of CIF’s members were parents at the local Head Start center, the Bloomingdale Family Program, that was well-known and well-loved for its wonderful, nurturing programs. CIF and Bloomingdale had a very close relationship. Bloomingdale was a very special place for me. I helped run the program for parents, co-facilitated its English Literacy class, and my two younger children had the great fortune of being part of the program.

After many conversations with CIF members during its Women’s Popular Education Program’s workshops, and then with staff at the Bloomingdale Family program, CIF helped establish a PAR-based project: Challenging Segregation in OUR Public Schools and Communities, led by CIF and Bloomingdale parents who were part of the local school district. These conversations made clear that parents were having a very trying time gaining seats for their children in our local elementary schools. As parents shared their stories, this belief kept surfacing that they were doing something wrong, that not being able to gain a seat for their child was a personal failing.

Listening to such stories, all of us in the room began to recognize that something else was going on that had absolutely nothing to do with what a parent was or wasn’t doing, but, rather, that it was about systemic racism and classism. We had no doubt that other parents were having the same experiences. We wanted to learn more!

It was from these discussions that the project to Challenge Segregation in OUR Public Schools was born. In a process that included street theatre, public events, community gatherings, and countless conversations, over 350 parents shared their stories and experiences, documenting the mechanisms of exclusion that prevented their children from being admitted to NYC public schools. As a result of a long process of envisioning and sustained organizing– including the publishing and sharing of a report in which CIF detailed its findings – the Department of Education instituted a much-needed policy change. For those involved in the organizing, the community power and deep relationships that were built and nurtured throughout the process were enormous and long-lasting.

At PARCEO, we have also seen these principles enacted in another context. In our work with university graduate students who are planning projects or initiatives with community-based groups, students have articulated many questions and concerns about how to enter these new spaces and communities, especially because they are seen as ‘representatives’ of institutions whose relations with community groups were often strained, at best. Preparing for these collaborations with different groups, and once beginning collaborations, the students began to think more deeply about what makes relationships meaningful and supportive of community efforts, rather than unhelpful or even exploitative. They also took in the importance and necessity of listening to, and reflecting upon, what community members were telling them about their needs, realities, and hopes for their collaboration. At the same time, the students recognized and identified the multiple roles and identities they also bring with them as members of different communities and groups.

Together, we have explored many of the principles listed above – often devoting time focusing on the notion of “expertise” and, not infrequently, working to challenge ideologies (of who is the expert, who has the knowledge) they had learned in their schooling. Some of the questions we have thought about together as part of this exploration include: Who is guiding the process and who is part of it from the beginning? How are decisions being made? Whom are you conducting research with, and whom is it for? How are different roles determined within a collaborative and participatory research process? What are the research questions? Who is determining them?

Reflections

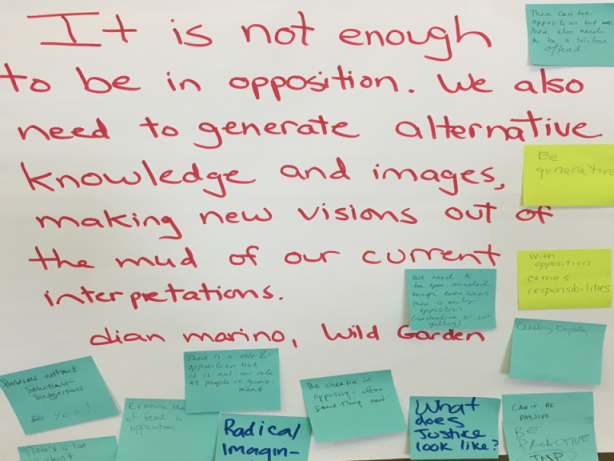

In my own experiences with PAR initiatives within different contexts, I have seen PAR principles guiding the work in ways that have enabled it to be deeper, more reflective, more thoughtful, more expansive and generous, and more flexible in an intentional way. Rooted in our imaginations, envisioning, histories, and collective wisdom, I believe these principles can help strengthen our educational spaces and learning, our community-building, our different forms of resistance, our longer-term campaigns, and so much more. Of course there are many who have never used the term “PAR,” yet have embodied these principles in their organizing and in their lives and relationships. On the other hand, as Dip Kapoor and Steven Jordan (2009) point out, some who speak in the name of PAR have at times co-opted and distorted its meaning to achieve goals that are exploitative rather than liberatory. Engaging in such processes always requires ongoing reflection about how to be accountable to one another and for the work we are doing. I find true excitement and energy – as well as hope and inspiration – in the multitude of ways that PAR processes can shape and inform, and help deepen and strengthen, our organizing, our relationships, and our work for justice.

[1] An interview with Marcos Guevara Berger on participatory action research in action; visit https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/knowledge_base/participatory-action-research-in-action-an-interview-with-marcos-guevara-berger/ for more about Marcos Guevara.

[2] Fundacion Iriria Tsochok was a Costa Rican NGO (1993-2003) that worked with the Indigenous and campesino communities of Costa Rica.

References

Center for Immigrant Families (2004). Segregated and Unequal: The Public Elementary Schools of District 3 in New York City. https://prrac.org/pdf/CIF_segregation_report.pdf

Freire, P. (2007). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Bloomsbury. (Original work published in 1970)

Gott, R. (2008, August 26). “Orlando Fala Borda”. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/aug/26/colombia.sociology

Kapoor, D., & Jordan, S. (Eds). (2009). Education, participatory action research, and social change: International Perspectives. Springer.

Rappaport, J. (2020). Cowards don’t make history: Orlando Fals Borda and the origins of Participatory Action Research. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

To cite this work, please use the following reference:

Nevel, D. (2022, July 7). Organizing for justice: The power of participatory action research. Social Publishers Foundation. https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/knowledge_base/organizing-for-justice-the-power-of-participatory-action-research/