Summary

This essay addresses the creation of an antisemitism curriculum by a social justice organization. The curriculum opens with some basic understandings of what antisemitism is and begins to consider what challenging antisemitism can look like from a framework of collective liberation. What follows is discussion of the racially, ethnically, economically, and culturally diverse Jewish communities that have lived throughout the world for centuries as well as global, historical examples of Jewish experience and antisemitism. From there–interwoven with broader social, political and economic context and realities–the focus is on antisemitism in the United States, beginning with the historical (e.g., immigration, race and racialization, Christian hegemony). We then look at antisemitism and how it manifests today (e.g., acts of violence, impact of rise in white nationalism, stereotypes/tropes, philosemitism) and the connections and intersections with other forms of racism and injustice. In order to understand what antisemitism is, it is also important to know what it is not, and here the discussion addresses the ways antisemitism has been misused to serve an anti-liberatory agenda and how (and why) criticism of Israel has been falsely equated with antisemitism. This discussion digs deeper into who has the “right” to speak about antisemitism and raises the issues of how data is used/misused, and why that matters. The curriculum moves to an exploration of what solidarities can look like and ways to deepen work to challenge antisemitism as part of our broader struggle for justice.

Context

PARCEO’s “Curriculum on Antisemitism from a Framework of Collective Liberation” addresses antisemitism through a liberation lens grounded in a deep commitment to challenging antisemitism and all forms of injustice – antisemitismcurriculum.org. This project grew out of conversations with educators and scholars, social justice organizers, and concerned individuals. We believe that community education is integral to our work for justice. The need for a curriculum on antisemitism within a pedagogic framework of collective liberation resonated as particularly important for this moment as rising white nationalist violence targets many of our communities, including Jews, Muslims, Black people, immigrant communities, trans and queer people, among others. The misuse of antisemitism and charges of antisemitism repeatedly directed at those fighting for justice for the Palestinian people add another layer of urgency to this project. Increasingly, and in creative and bold ways, social movements are envisioning and building together to challenge all forms of injustice and to deepen and strengthen collective work for justice and dignity for all peoples. Our hope is that this project will contribute to that broader effort.

Antisemitism from a Framework of Collective Liberation

During a workshop with NYC public school teachers this Fall, a few months into Israel’s brutal assault on the Palestinian people of Gaza, we presented our curriculum on antisemitism from a framework of collective liberation. The group of 30 teachers, from kindergarten through high school, were eager for more information, analysis, and teaching tools on antisemitism from this lens. They also welcomed a chance to build community and share experiences and tactics to support each other in a rapidly hostile environment for dialogue and information about justice for Palestine. One of the realities hanging over people’s heads was the relentless accusations of antisemitism, and potential consequences, for trying to engage with their communities about what was happening in Gaza.

The Israeli state and its advocates have hurled false accusations of antisemitism at supporters of Palestinian justice since the years following the Nakba–the catastrophe (in Arabic) of 1948 when 750,000 Palestinians were uprooted from their homes and land before and during Israel’s creation. This phenomenon has escalated in recent years, becoming even more virulent these past months as Israel has inflicted unfathomable violence on the people of Gaza and as the movement for justice for the Palestinian people has grown and strengthened across the globe. The strategy is quite simple: When you can’t attack the message, attack the messenger.

These accusations of antisemitism take different forms. They are being promoted through, for example, house resolutions; congressional hearings of university presidents; and ongoing efforts to criminalize and penalize those speaking out in their schools, universities, workplaces, and communities against Israel’s ongoing violence. These tactics are not about fighting antisemitism, but rather are intended to destroy our movements for justice and those who are part of them.

Discussion and analysis of antisemitism in the US—from those put forth by mainstream Jewish organizations, like the Anti-Defamation League, to the White House strategic plan on combating antisemitism that relies heavily on the Department of Homeland Security, the FBI, and other law enforcement agencies –are seriously distorted and compromised by the conflation of antisemitism with criticism of Israel and Zionism, among other factors.

Education on antisemitism must insist on fully separating and distinguishing the fight against actual antisemitism from false attacks of antisemitism on seekers of Palestinian justice. Further, as rising white nationalist violence targets many of our communities, including Jews, Muslims, Black people, immigrant communities, trans and queer people, among others, the need for a curriculum on antisemitism within a pedagogic framework of collective liberation, rooted in an understanding that antisemitism cannot be fought in isolation from other forms of injustice, is particularly important for this moment. Our curriculum on antisemitism from a framework of collective liberation was borne from these realities and considerations.

The curriculum grew out of many conversations with partners in our social justice communities as well as with educators, both at universities and in K-12 education. PARCEO embarked on this undertaking together with an active group of community advisors and reviewers, who are educators, scholars, and activists rooted in our many movements for justice.

This project also reflects a commitment to community education as integral to our work for justice. Drawing upon extensive resources, the curriculum sessions include excerpts from, and links to, articles and books; videos (including our own roundtable conversations and interviews ranging from one minute to an hour); visuals; poetry and music; and reflection questions for framing and analyzing a range of issues. A number of resources and hand-outs supplement the sessions.

The curriculum offers opportunities for in-person or on-line learning and is designed to serve as a resource for social justice and community-based organizations, universities and middle schools/high schools, religious and cultural institutions, and other groups and communities.

As part of the curriculum, we look at the richness of Jewish life and culture throughout the centuries and the diversity of Jewish experiences, histories and geographies. Jews reflect racially, ethnically, economically, and culturally diverse communities, experiences, and histories and have lived throughout the globe for centuries. There are white Jews, Jews of color, and Jews from different parts of the world, including Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East. We share maps, music videos, and images that show the different Jewish ethnic groups including: Ashkenazi Jews, who are from Eastern and Western Europe and Russia; Mizrahi Jews and JSWANA, who originate from Middle Eastern, North African, and Central Asian countries; Sephardi Jews from Spanish and Portuguese backgrounds and from Balkan countries; Jews from Ethiopia, Uganda, India, and China. And we show how each of these, and many other different contexts, histories, and localities have necessarily impacted experiences of anti-Jewish oppression and violence and antisemitism differently.

We discuss antisemitism and Jewish experience historically, including immigration, race and racialization, and the role of Christian hegemony. We also explore the different manifestations of antisemitism today, including, for example, tropes and stereotypes, conspiracy theories, philosemitism, and the rise of white nationalist violence.

In contrast to timelines that characterize Jewish histories only in relation to antisemitism and as eternal, cyclical, natural, and never-ending, we offer a perspective that reflects Jewish experience as including, but not limited to, antisemitism, and locates antisemitism in relation to local conditions and realities and other systems of oppression. In our section addressing these different perspectives of Jewish experience, we include excerpts from different scholars and educators, including from Professor Barry Trachtenberg, historian of modern European and American Jewry: “If one accepts antisemitism to be eternal, and not a consequence of social or historical factors, then it is a fact of life that will forever push Jewish people into defensive postures. It will make us more nationalist, more reactionary, more militaristic, and more closed off from the rest of the world.”

As part of this discussion on the different perspectives on antisemitism, we reflect upon the following question: How do these different ways of viewing history impact an understanding of antisemitism? This historical perspective not only grounds our understanding of how we see antisemitism, but also leads us to think about responding to it as part of and connected to other struggles against different forms of injustice. One tool that helps elucidate these different perspectives and deepens a historical analysis is a slideshow that outlines historical moments of Jewish experience and antisemitism, including intersections with other targets of systemic violence and oppression and the ways Jewish experience included but was not limited to antisemitism. It also recognizes the ways that different Jewish communities around the world have had different experiences with violence and discrimination, for example, Mizrahi histories and experiences of antisemitism are different from Ashkenazi histories and experiences of antisemitism. An image of Maghrebi women in a sitting room in Morocco is overlaid with a text on the context of French colonialist displacement. Texts recounting the growth of European fascism and the ways that Jews, along with many others, were targets of authoritarian nationalism and antisemitic and racist ideology, are placed next to antifascist examples of resistance.

What differentiates our approach from other timelines that discuss antisemitism as the defining, never-changing experience of Jewish experience is an understanding of how critical context is when looking at Jewish experience, the complexity of Jewish life, and the reality of antisemitism in different locations.

Another section of the curriculum focuses on what is, and what isn’t, antisemitism. While it is critically important to understand what antisemitism is, equally important is to understand what antisemitism is not. Organized campaigns are derailing and mis-stating the meaning of antisemitism and falsely conflating it with criticisms of Israel and Zionism. Distorting what antisemitism is furthers political goals that are both harmful to our work for Palestinian justice and to combating antisemitism.

One of the many ways we’ve seen this playing out in recent years is through the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance Working Definition of Antisemitism (IHRA-WDA), which includes examples of antisemitism that are squarely about criticism of Israel. We see how those who are pushing for this definition of antisemitism to be adopted by universities, governments, and others are attempting to silence critics of Israel’s human rights abuses. The IHRA is one example of increasing attempts being made to discredit critics of Israel by accusing them of antisemitism. Palestinian and scholars and activists of color have, in particular, been routinely harassed and harmed by these attacks. It is important to understand, however, that the charge of antisemitism can be wielded to silence such criticism even in the absence of the IHRA. A few examples of consequences suffered by critics of Israel these past months include the names and faces of students at Harvard who signed pro-Palestine statements appeared on trucks in Harvard Square under the heading “Harvard’s leading antisemites”; a Berkeley law professor wrote a WSJ op-ed urging employers not to hire his own students because of opposition to Israeli actions in Gaza; the appearance of a Pulitzer-Prize winning author at NYC’s 92nd St Y was canceled because of his criticism of Israel’s actions in Gaza; and two colleges have banned SJP (Students for Justice in Palestine) and JVP (Jewish Voice for Peace), two leading anti-Zionist organizations on campuses, among many other examples.

We include many excerpts addressing this critical issue in the section on what is and what is not antisemitism. One is from Jewish organizations across the globe:

40+ Jewish groups worldwide oppose equating antisemitism with criticism of Israel – JVP (jewishvoiceforpeace.org): “The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism, which is increasingly being adopted or considered by western governments, is worded in such a way as to intentionally equate legitimate criticisms of Israel and advocacy for Palestinian rights with antisemitism, as a means to suppress the former. This conflation undermines both the Palestinian struggle for freedom, justice and equality and the global struggle against antisemitism. It also serves to shield Israel from being held accountable to universal standards of human rights and international law.”

Another excerpt is from Palestinians and Arab educators, journalists and intellectuals – A group of 122 Palestinian and Arab academics, journalists and intellectuals express their concerns about the IHRA definition – Just International (just-international.org) and includes the following:

“… In recent years, the fight against antisemitism has been increasingly instrumentalised by the Israeli government and its supporters in an effort to delegitimise the Palestinian cause and silence defenders of Palestinian rights. Diverting the necessary struggle against antisemitism to sever such an agenda threatens to debase this struggle and hence to discredit and weaken it. ….”

As we explore this issue, we also discuss and share a video on how the misapplication of what antisemitism is requires us to look more carefully at the data on antisemitism. That is, when an organization, like the ADL, falsely considers criticism of Israel as antisemitism in their data, the results will necessarily be skewed and inaccurate so it is crucial to understand the source, who is creating the data, for whom, and to what end. Likewise, when relying on a hate crimes framework, we must be vigilant so that anti-hate and anti-violence work is not co-opted to further entrench the domestic violent extremism framework and expand the “War on Terror.” Our curriculum offers both analysis and examples of ways we can stand together against the multiple forms of violence and criminalization many of our communities face in different ways.

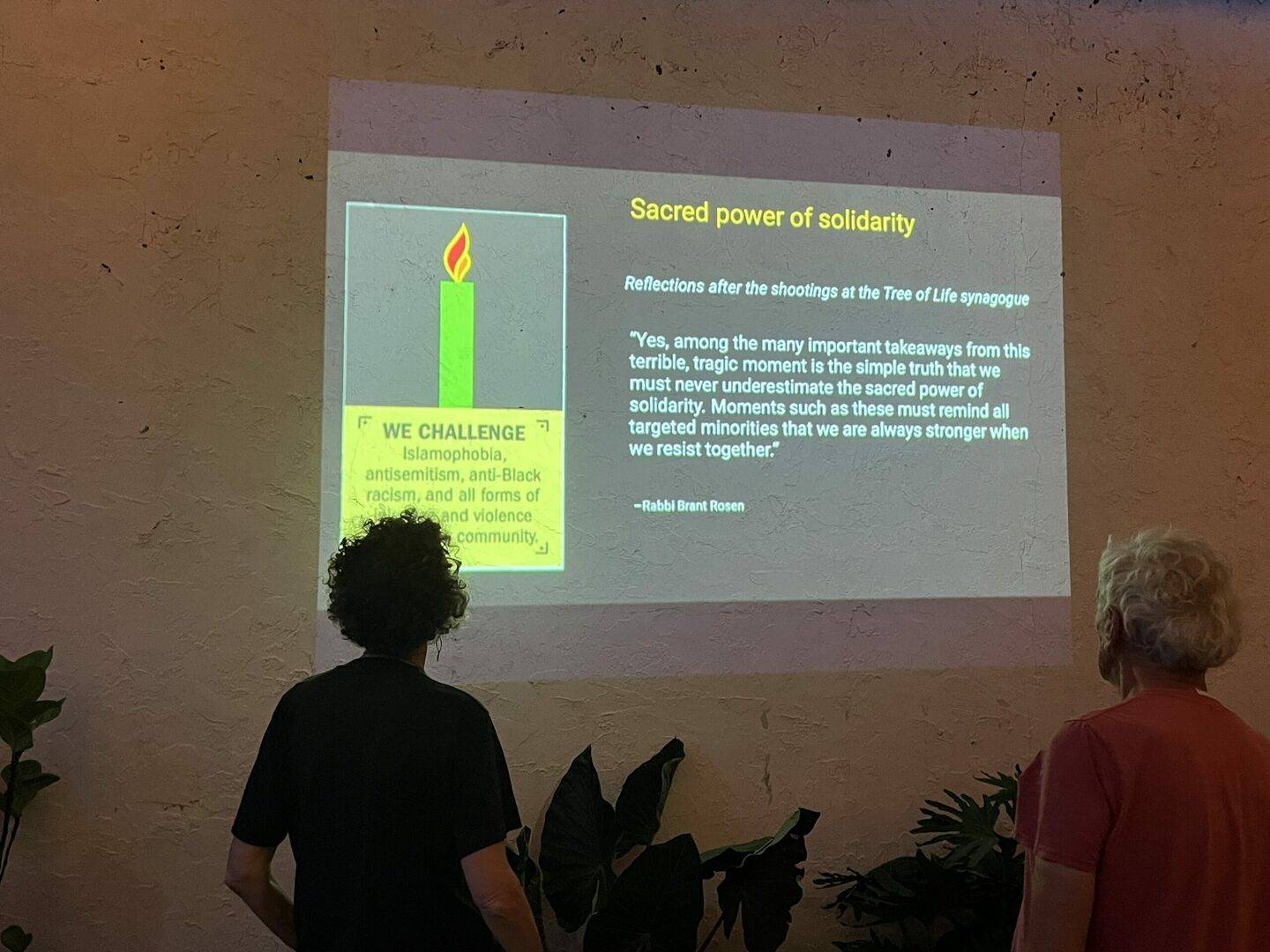

When school districts and politicians urgently create task forces for fighting antisemitism, our curriculum offers a critical perspective that roots our struggles against antisemitism, Islamophobia, anti-Palestinian racism, and anti-black racism as intertwined. Examples in the curriculum of groups fighting for collective liberation historically– from Jewish and Italian immigrant workers fighting for labor rights, to current abolitionist and disability rights movements–offer examples of standing together against the multiple forms of violence and criminalization many of our communities face in different ways.

Interwoven throughout the curriculum are the voices of organizers and educators who speak about why understanding antisemitism from a collective liberation lens makes so much sense and furthers our work for critical inquiry and educational justice. As scholar, organizer, and minister Nyle Fort, who is also a community reviewer of the curriculum, makes clear in one of the curriculum’s roundtable conversations: “What does it take to transform the world? What does it mean to transform ourselves in the service of that work? So, when I think about this project of thinking about antisemitism in the context of collective liberation, what other way is there to think about it if we are really talking about collective liberation?”

And as community leader and international educator Sister Aisha Al-Adawiya, another community reviewer of the project, so eloquently states: “This is exactly where I believe we need to move as human beings. Standing up for each other in a real authentic way. No cameras rolling. Just the human spirit calling on us to say, ‘This is not right and I have to say something’.” – Finding the Inspiration to Stand Up for Each Other, An Interview with Sister Aisha Al-Adawiya

Posing Questions for Fuller Understandings

At the end of the curriculum, we pose questions like the ones below as we begin to think more deeply about our work as educators and organizers moving forward:

- As we engage in our work for justice, how can we think about genuinely challenging antisemitism and all forms of injustice from a framework of collective liberation?

- What are ways we can continue to build together, learning from and with those who have been deeply immersed in these issues?

- How do we learn, work and build along with those who are exploring new ways of organizing?

- How can we enter spaces and begin laying the foundation for organizing that is truly rooted in movement solidarities?

- How can we enact our values and principles in our day-to-day actions?

Increasingly, and in creative and bold ways, social movements are envisioning and building together to challenge all forms of injustice and to deepen and strengthen collective work–in our schools and in our communities–for justice and dignity for all peoples. Our hope is that this project will contribute to that broader effort.

To cite this work, please use the following reference:

Mehta, N., & Nevel, D. (2024, January 28). Antisemitism from a Framework of Collective Liberation. Social Publishers Foundation. https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/knowledge_base/antisemitism-from-a-framework-of-collective-liberation/