Part 2: Reflections on the 2017 Cartagena Assembly for Knowledge Democracy

Transforming practices and practice architectures for democratising global conversations: Reflections on the intersubjectivities of the Global Assembly for Knowledge Democracy

Yindyamarra Winhanganha – ‘the wisdom of respectfully knowing how to live well in a world worth living in’

I begin this essay, reflecting on the genesis, development and experience of the 2017 Global Assembly for Knowledge Democracy I co-chaired with Lonnie Rowell, with these words from Wiradjuri language, an Australian First Nation language community located in the state of New South Wales (NSW). For my part, it was the Wiradjuri[1] spirit of yindyamarra winhanganha – to go gently and respectfully forward for the good of humankind – that framed the planning and conduct of the Global Assembly for Knowledge Democracy (the Global Assembly). In particular, I was inspired by Wiradjuri Elder, Dr Uncle Stan Grant, Sr AM (2016, p. 91) who said:

Yindyamarra has a big meaning for a little word, and it means so many different things. Not just respect other people, respect yourself, respect the land, respect humanity.

With permission, these were also the words I used to open one of the Global Assembly’s pre-assembly workshops (described below) held in Cartagena, Colombia, involving participants from action research networks from across the world. These participants were interested in respectfully rethinking knowledge, knowledge practices and knowledge democracy.

Planning the 2017 Global Assembly for Knowledge Democracy

At the outset, Lonnie and I knew from our earliest planning discussions for the Global Assembly (over Skype for at least 18 months before the Global Assembly took place – first together then with others who later joined the planning committee) that we had to be overtly conscious that our genuine good intentions should be held to account in ways that could not be taken as reductionist, rhetorical or tokenistic; remembering that our,

…good intentions, perspectives, practices, and analyses are always subject to cultural bias, ethical oversights, and latent agendas, and must rightly be questioned to avoid being considered highly tokenistic and unethical (Trudgett, 2013).

With a deep sense of responsibility and accountability, this was always at the forefront of our thinking about the practices before and during the Global Assembly, where the transformative activist stance we all aspired to in our everyday ‘researcherly’ lives was given impetus on those days.

Our planning involved working on the program for the pre-assembly workshops and the Global Assembly itself. For Lonnie and I, the days and nights we had spent planning – he in the US and me in Australia – began in an effort to move beyond the status quo and oft-felt inertia of static views in a dynamic ever-changing world – where democratic sensitivities were being eroded by performative pressures on the work of communities, educators and researchers across the world. These ideals came to fruition when we met in person in Cartagena Colombia, when our online planning for the Global Assembly continued face-to-face (sometimes over dinner with our new colleagues – pictured below) without skipping a beat.

Photo 1. Taking a break together: Planning team members and some Assembly participants

Our collective aim to “transcend the ‘givenness’ of the world” to create conditions for “alternative futures” (Stetsenko, 2014, p. 196) meant that our own collegial conversations continually examined and adjusted the activities we had planned for the Global Assembly. This was critical if indeed we were to create practice architectures or the conditions that would actualise a transformative experience for all present. We were compelled at every turn to remind ourselves that our own practices in the event itself must not be practices with untoward consequences, that are irrational and unreasonable, unproductive and unsustainable, or unjust and undemocratic.

Pre-Global Assembly Workshop in Cartagena: Tuning into intersubjective sensemaking across global research networks

I led one of the pre-assembly workshops “Networks, Action and Knowledge Democracy”[2] in Cartagena that aimed to bring together action research network leaders and other interested scholars from around the world to share and develop deeper insights on knowledge democracy through inter-network engagement. In the spirit of open dialogues, participants from the different networks came together in an open communicative forum to discuss ways to share, respect and advance knowledge in contemporary times. The workshop was framed by these overarching questions:

- How are issues of knowledge democracy relevant and experienced by people working in participatory action research spaces?

- What is the nature of these spaces?

- What are the practices of knowledge? Practices of action? Practices of participation?

- How are the practices and issues similar to those addressed by Orlando Fals Borda and others in the 1960s – 1980s?

To arrive at tentative answers to these questions, the workshop was designed to have the participants from different national and international cultural and intellectual traditions consider and transform ways we collectively work towards democratic action.

In a deliberate attempt to unsettle the taken-for-granted assumptions that English is the language commonly spoken at such global events (even ones held for example in Spanish speaking nations like Colombia where the Global Assembly was held), I began this workshop with the video Yindyamarra Yambuwan: Respecting Everything (Sullivan & Grant, 2016) spoken entirely in Wiradjuri, knowing that this was a language not heard before by those present. This initial shared sensemaking experience of listening to and interpreting the Wiradjuri story in the almost lost Wiradjuri language (but now in the process of reclamation) was an intersubjective one. It was a practice which became an influential practice architecture or shaping condition that influenced our human interconnectivity, transforming the sayings, doings and relatings we practiced individually and collectively on that day and subsequently throughout the ARNA Conference and the Global Assembly.

On the complexity of individual and collective embodiment within and for the intersubjective spaces in which humans connect, Stephen Kemmis (2022, p. 76) recently said

By ‘intersubjective space’ I mean the ‘extra-individual’ … space that exists between people as individual subjects. While much social theory imagines the space between individuals to be an empty void across which one individual addresses another, or in which one encounters another, I do not regard this space as ‘empty’. On the contrary, it is a space of human interconnectivity.

Critically, in this pre-Global Assembly workshop, new intersubjective spaces for human interconnectivity were formed – where our individual and then distant standpoints and experiences became entangled with the standpoints and experiences of others present, creating for ourselves new semantic spaces where our words, languages and discourses were made anew, where our actions, activity and interactivity in the material space were filled with ‘extra-individual’ newly formed social imaginaries. In this space, using the participatory practice of ‘dialogue circles’, participants worked towards developing commitments for action for the democratization of knowledge ecologies.

Amidst the workings of the pre-assembly dialogues coming together as a praxis-oriented research community committed to the social good, we endeavoured to respond genuinely to “the need to build transparent and collaborative procedures that are justifiable and transformative in the making” (Groundwater-Smith, 2017, p. 14). Edwards-Groves and Murray (2008, p.174) argued amidst the complexity of contemporary societies, that for educational work to be transformative, aspirant gatherings like the Global Assembly,

…must provide a genuine communicative space between researchers, educators and Aboriginal peoples, a space which enables all citizens to be treated as a vital resource for knowledge building; this has the potential to create far-reaching changes to social relations with people in mainstream communities (p.174).

Learning about Yindyamarra Yambuwan also sensitised all present – from countries across Europe, Scandinavia, the Americas, Africa, Asia and Australasia – to face our oft latent views about democracy, knowledge, culture and language veiled by unquestioned and unspoken privilege.

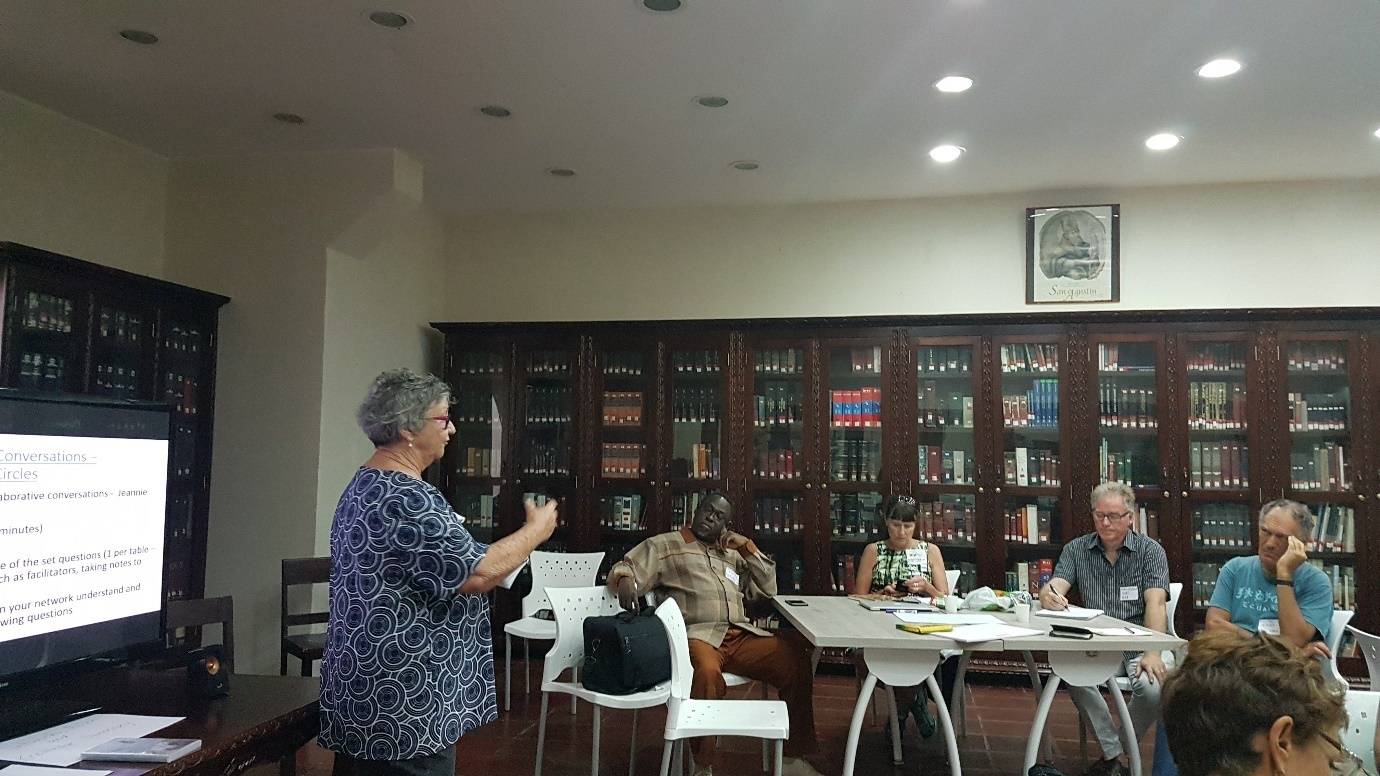

We were honoured to have yindyamarra winhanganha contextualised in the introductory session of the workshop in Cartagena, through an experience led by Jeanie Herbert AM, Australian First Nations Elder from the Njkinja nation in the Kimberley region, Western Australia. Jeanie was honoured with the ‘Order of Australia’ for her contribution to education for Australian First Nation peoples, and was Professor and Pro-Vice Chancellor Indigenous Education and Foundation Chair Indigenous Studies Research Chair (Charles Sturt University, Australia). Jeanie, pictured below, challenged us to engage in critical collaborative conversations – based on the Australian First Nations practice of ‘yarning circles’ aligned with the Western notions of ‘dialogue circles’ – to ask and answer questions about knowledge and knowledge democracy from our various theoretical, epistemological and ontological standpoints. Specifically, we discussed these questions:

- What is knowledge democracy?

- How do we understand knowledge from our own cultural and intellectual traditions? What do these concepts mean for our work within our network?

- How do we respectfully work towards equity within our inherited ‘intellectual spaces’ as it relates to our network?

- How do we as action research networks recognise, support, discuss and engage with questions concerning epistemologies, methodologies, theories and methods to advance the circumstances for those we are researching and researching with?

From the outset, Jeanie guided our collective mission for the common good and service to humanity into a space of intersubjective sensemaking about the task we had set ourselves for the Global Assembly.

Photo 2. Jeanie Herbert AM, Australian First Nations Elder from the Njkinja nation in the Kimberley region, Western Australia leads part of the Pre-Assembly workshop

With this in mind, we critiqued current practices in our respective contexts, and fields of practice, disciplines and research domains. These varying intellectual resources became bound together by our shared purpose which sought to understand the alignments and disalignments about knowledge and democratic ways of practising. Thus, the work was also transformative, in that from the beginning of our work together that day, we were both challenged and enlightened by our together-experience of not knowing, not understanding. It was the ordinary experience we shared at this moment which proactively opened us – outwardly and inwardly, collectively and individually – towards new intersubjective spaces reflective of yindyamarra winhanganha; and shaped our collective stance-taking and vision-setting for the days of thinking and sharing that were to come in Cartagena. As Anna Stetsenko (2014, p. 192) reminds us,

The future never simply awaits us but instead, is created by our own actions in the present – through even seemingly mundane deeds by common people in their ordinary lives (implying that actually no deed is completely mundane, no person completely common and no life completely ordinary).

For us, this practice was the right thing to do at the time and could be described as being reflective of a praxis stance. As Groundwater-Smith (2017, p. 18) reflected,

In effect, praxis becomes a form of communicative action through which participants seek to read common understanding and form their actions through which reason, argument, consensus and cooperation as opposed to forms of strategic action that satisfies personal goals and aspirations (after Habermas, 1984). Praxis is necessarily achieved through public dialogue rather than as an individual and often implicit exercise of power.

After the introductory session, leading action researcher from Sweden, Professor Karin Rönnerman (pictured standing in the image below), reminded us of the need to recognise the challenges for consensus in defining democratic transformation, framing transformation itself as necessarily contested and bound by normative, ideological bias and not free from the constraints of oppression and power.

Photo 3. Professor Karin Rönnerman speaking at the workshop

Drawing from her deep knowledge of dialogue circles and democratic ways of being and folk enlightenment in the rich Nordic tradition, Karin led the next segment of the workshop. She opened with the argument that notions of democratic transformation must be overhauled, examined, dissected and problematised through our various historical and cultural lenses to ensure a more profound understanding of its aspirational implications for critical educational praxis. In particular we discussed what this meant for the work of the Global Assembly – especially in terms of what it meant for living and educating for a good life for humankind. It is Carr and Kemmis’s (1986) suggestion that education is about critical praxis, requiring a person to demonstrably “make a wise and prudent practical judgement about how to act in this situation” (p. 190) that rang out through the thinking on that day. In their view, education is witnessed in the actions of people that reflect an observable commitment to human well-being – and indeed human flourishing, the search for truth and the respect of all others (Carr & Kemmis, 1986).

Here, the Aristotelian notion of eudaemonic flourishing (Aristotle, trans. 1925) resonates with Dewey’s idea that humans are ‘so “thoroughly social” that we cannot conceive ourselves otherwise than as a member of a body or a community (Dewey 1893/1971, p.285). In regards to educational research, I draw on Kemmis et al.’s (2014) definition of education:

Education, properly speaking, is the process by which children, young people and adults are initiated into forms of understanding, modes of action, and ways of relating to one another and the world, that foster (respectively) individual and collective self-expression, individual and collective self-development and individual and collective self-determination, and that are, in these senses, oriented towards the good for each person and the good for humankind. (p.26)

This view highlights a double purpose of education: to help prepare people to live well in a world worth living in (Kemmis & Edwards-Groves, 2018). Thus, education and educational action research has individual as well as broader societal goals with both formational and transformational aspirations. As Kemmis et al. (2014) explained: for the individual, education concerns the formation of persons, and in terms of the social, it concerns the formation of collectives in terms of groups, communities and societies. The substance of the collaborative conversations we engaged in at the pre-assembly workshop culminated in newly formed propositions, themes or questions about individual and collective transformation to be shared as a part of the June 17 Global Assembly for Knowledge Democracy. Our collated notes recorded throughout the day, helped to establish a shared context in which the process of examining knowledge democracy linked with efforts to foster transformative educational environments.

The Global Assembly

At the Global Assembly, the intention was to ground the understanding of participants roles in an educational standpoint – one where education resides as a right for all – one where a critical, praxis-oriented and multi-directional stance prevails (Rönnerman et al., 2017). This required ‘a democratic sensibility’, where multiple cultural perspectives were explicated and taken seriously (pictured here as people from multiple cultural ontologies came together with “one beating heart”).

Photo 4. A working group during the Assembly

In our individual and collective endeavour, sharing (in our own culturally determined ways) our concerns for broader moral and ethical imperatives that extend beyond the technical neoliberal machinery was paramount. This sensibility incorporated understanding our practices as participants in the Global Assembly, as necessarily attending closely, possibly only, to the good for each person and the good for humankind.

In our table discussions, our critical concern for the morality and ethics of our then-and-there educational practices foregrounded the praxis-orientation outlined decades ago by Carr and Kemmis (1986). This sensibility is praxis-oriented[3] (Kemmis et al., 2014), educationally concerned, enabling, socially just and democratic (Rönnerman et al., 2017). To incorporate this sensibility, we considered what it meant for our work in and for the Global Assembly and we sought to emphasize our work overall as being inherently educational, as reconsidering the kinds of day-to-day practices characteristic of the good life for humankind, namely, practices that overtly and visibly enact and secure (1) a culture based on reason, (2) a productive and sustainable economy and environment, and (3) a just and democratic society. This was not simply a reflective, aspirational or semantic exercise; it was an exercise in renewing our own orientations towards and practical commitment to praxis – a necessary condition for securing knowledge democracy in real and practical terms. Critically, then, if knowledge democracy – and the practices that support it – was an inherent goal of the Global Assembly, then, as Kemmis et al. (2014, after MacIntyre, 1981) believed, practices of knowledge democratization must be an initiation into the sayings, doings and relatings that make those practices possible: (1) forms of understanding (or sayings) that support and secure a culture based on reason, (2) modes of action (or doings) that support and secure a productive and sustainable economy and environment, and (3) ways of relating to one another and the world (or relatings) that support and secure just and democratic societies. During the Global Assembly we thus created, for a day, new intersubjective spaces within which we encountered other languages, cultures, races and social-political circumstances. In these new spaces we were initiated into new forms of sayings, doings and relatings, but more importantly, we renewed our commitments to knowledge democracy by speaking in practical ways about what specifically we could do in our own locales and worksites.

In smaller groups on the day of the Assembly, we collectively considered ways the future is formed through the democratic practices of the present. We located ourselves “in the here and now” (Stetsenko, 2014, p.196) to critique our current practices that called to attention the need for future action that primordially should lead us to “live well in a world worth living in” (Kemmis et al., 2014, p. 25). In doing so, in these new intersubjective spaces, we explored an imagined alternative “possible future” (Stetsenko, 2014, p. 196) where the potential for new actions prioritised the need for creating conditions where an active and activist citizenry prevails in a world worth living in. With this in mind, the roundtables created conditions for reconsidering ‘transformation’ in light of a transformative activist stance underpinned by critical educational praxis.

Photo 5. Roundtables underway

As our dialogues took shape in the assembly, we drew out how transformation is differently understood and how a sensibility to it can be (re)made within education practices and our local research communities for the purpose of individual and collective emancipation, agency and growth. Together, we problematised conditions for societies, for research and for education, shifting our mandate for educators and researchers to be stewards of activism in and for critical educational praxis in the particular communities in which we worked. These dialogues had strong implications for setting future directions for democratising knowledge that we agreed must not be colonised by Global North ideologies (for instance), and where practices espousing and promoting emancipation, agency and growth are legitimately grounded in democratic ways of working that begin with a listening-first premise.

In my table group, for instance, we returned to notions of a democratic core informed by Dewey’s thinking about education (for example), where knowledge and learning is culturally, socially and discursively formed, informed and transformed when the local site-based conditions which enable and constrain action are overtly recognised and responded to. Critically, we agreed that such democratic practices involve genuine respect and reciprocity and must be done in consultation with and in the company of local citizens, where together in practices, persons (there-and-then) strive for:

- mutual understanding and comprehensibility,

- the formation of interpersonal relationships (that account for varying balances of power, agency and solidarity), and

- the coordination of human conduct in their activities (Edwards-Groves & Rönnerman, 2021, p. 16).

Striving for the formation of active and informed citizens committed to a democratic way of life able to withstand neoliberal accountancies and accountabilities requires recalibrating intentions to align with and respond to local voices, knowledges, needs, aspirations and circumstances. Therefore, as the day and the dialogues unfolded in the Global Assembly, participants were reminded that we are accountable for our actions (then and in the future) and for the promises we make for emancipation, agency and growth. Notions of accountability were coupled with the need to frame our ongoing actions by always asking – in whose interests are we acting? whose interested are being served? Consequentially, this means a distinctive shift away from entrenched colonising practices largely focused on the interests of the colonisers.

This shift, and call to action, equally calls for shifts in power, solidarity and agency – and highlights Stetsenko’s demand for educational researchers to stand up with communities under pressure to “co-create” (2018, p.54) opportunities for radical emancipatory change based fervently on democratic education principles. This is a turn towards individual and collective flourishing, and rather than solely a turn inward, it is a turn outward in support of a citizenry which “transcend(s) their limitations” (Stetsenko, 2008, p. 483). Here, it is important to consider Stensenko’s 2019 argument suggesting that true transformation where solidarity, advocacy, equity, agency and democracy reside, can only be created through purposeful, critical, and collaborative struggle. Our dialogues at the assembly reminded us that as researchers, we are activist professionals uniquely placed to engage in this struggle, with and in the communities we work to create what “ought to be” (Stensenko, 2019) – to create locally relevant conditions of possibility for living well in a world worth living in.

Challenging educational praxis through a transformative activist stance for democratic education

During the roundtable events, we drew on intellectual and epistemological resources long espoused by notable proponents of critical transformative action and activism (Wilfred Carr, Stephen Kemmis, Orlando Fals Borda, Paulo Friere, Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Lawrence Stenhouse, among many) to challenge our latent or static ideations of transformation.

Photo 6. Multiple roundtables in session

The residual need to challenge inertia and the status quo, or even take account of false, or self-proclaimed benefits of our local action projects, added primacy to our intentions to act in ethical and prudent ways. In this, there was a shared conviction and commitment to ensure that our efforts at the Assembly would not simply be reduced to being a ‘talk fest’, rendering the richness of the seeds sown on that day wasted by inaction. Historical conceptions of praxis as ‘morally committed and right and just action’ lay the foundations for, as Kemmis (2021) argued, reclaiming critical educational praxis in the current times we were discussing. Confronting this key aspiration was the challenge of ‘what to do’ to include those who unfortunately could not attend the event in person but sought a voice in the proceedings. This meant creating practice architectures that would make participation possible for a far greater number than the 350+ in attendance in Cartagena. We did this by, for example, creating a synchronised online chat forum that traversed, social, cultural and technological borders, where the processes and content of the day were described, explained, critiqued and challenged by the online participants via online chat and video calling.

Photo 7. An on-line Chat Forum during the Assembly

In this sense, we opened up inclusive communicative spaces for an exchange of multiple perspectives and interpretations of educational concepts, theories, and issues, and the ‘translation’ of these into new contexts, domains, and traditions. In pursuing this, we aimed to provide access, through multimodal processes, intercultural and multidimensional thinking, learning, discourses and translanguaging for those not in attendance.

Critical Transformative Dialogues

As a form of reflexive professional agency, critical transformative activism requires a praxis-oriented stance where transformation is evidenced in the emergence of practices (sayings, doings and relatings), that are generative of change that matters for individuals and collectives in local sites. For participants in the Global Assembly this meant reconsidering what is right and just to do under local conditions, dispelling postmodern anxieties for rule-following, and rejecting meeting KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) or ‘tick-box accountancy’ to proactively transform the fabric of social life experienced in the double reality of system and lifeworld (after Habermas). On the day of the global assembly, as we sat at roundtablesaction taking and activism in our professional educational lives were discussed in view of the interconnected realms of transforming the technical, practical and critical realms of our worlds. For me, our actions and interactions on that day reminded me of Barry MacDonald et al’s (1975, p.49) provocation,

the citadel of established practice will seldom fall to the polite knock of a good idea. It may however yield to a long siege, a pre-emptive strike, a wooden horse or a cunning alliance.

Photo 8. Roundtable as the potential site of new alliances

The dialogues that took place in Cartagena created open communicative spaces for imagining the cunning to strike with purpose towards “the future and charting the course of actions that could help [achieve] social change” (Stetsenko, 2014, p. 186). Moreover, these dialogues set the post-assembly challenge for all present to enhance human flourishing that should embody educational action as aiming to support others to “live well in a world worth living in’ (Kemmis et al., 2014, p. 25).

Going forward – reigniting the site-ontological imperative for transformative action

Just as the urgent intent and processes were recorded as an aspirational and transformative flow through the images captured by the artist-in-residence (pictured below), going forward means reigniting our drive to ‘make’ transformations sustainable, enduring and dynamic for our uncertain times. This is not a future task – but an urgent now task. It is a task made even more pressing given our current societal contexts of enduring change and global shock, prompted by a deadly pandemic, worsening climate conditions, a devastating renewal of war, continued acts of racism, famine and disease as well as increasing dissent and disruption within the (seemingly) stable social and economic systems of the global north. In this sense, perhaps the key task for a future Global Assembly is to reassemble its drive for urgent efforts to establish education and research practices as a fundamentally transformative imperative for all.

Photo 9. Documenting the Assembly: Dr. Pencil at work

We must recall our conviction to act – rouse the mettle of our resolve, to unsettle the status quo, the taken-for-granted, the banal everyday routines of our system and lifeworld circumstances. For education this is an imperative since education itself is under pressure in the current neoliberal climate of testing, accountability and performativity to move backwards, not forward. As I have argued with colleagues Peter Grootenboer and Tracey Smith (2018, p. 136):

what is left in its wake seem to be more perfunctory technical schooling practices and dispositions devoid of ‘sensitivity’ responsive(ness) to the site, and of the needs and circumstances of those practising there – where education practices strive for fostering the good of the individual and the good of society.

Summing Up and Looking Forward

Calling back the urgency we proclaimed at the Global Assembly requires complexity thinking that,

compels researchers to consider how they are implicated in the phenomena that they study – and more broadly, to acknowledge that their descriptions of the world exist in complex (i.e., nested, co-implicated, ambiguously bounded, dynamic, etc.) relationship with the world (Sumara & Davis, 2012, p. 358)

With this in mind, the onus is on us to not only problematise the conditions for education and our part in the confronting and taking account of uncomfortable truths (Boyle et al., 2021) in our scholarship, but to be committed to a better future for all.

The notion of commitment (to the future) suggests that persons not so much expect or anticipate the future, but rather, actively work to bring this future into reality through their own deeds, often against the odds, that is, even if the future is not anticipated as likely and instead, requires struggle and active striving to achieve it. This refers to persons and communities struggling for what ought to be, thus bringing the future into the present in spite of the powerful forces that are pulling in other directions, that is, while resisting and overcoming the present in its status quo, power hierarchies, and contradictions. The notion of commitment, therefore, is agentive and political, as well as ethically-valuational, because it entails struggle for the future rather than merely its anticipation (Stetsenko, 2014, p.193)

To continue on – five years post Global Assembly – we must reaffirm the commitment to the struggle for a better world that we (individually and collectively) made on the 17th June, 2017. To do this, we must heed the words of Kemmis et al. (2014) who argued, that to change (current and future) practices, we need to change the practice architectures that prefigure the conditions of our daily work and social endeavour. This means, for the Global Assembly, recognising our then-commitment to change our own (researching, leading, learning, teaching, professional) practices to bring about changed circumstances that enable all local and global citizens to live a good life. Each of us in attendance made for ourselves our own personal resonances and resolutions to act. For example, for my part, this meant taking seriously what the act of walking respectfully around the room in the final moments of the assembly, with our hands gently tapping our chests in unison to represent our humanity “with one heart beating”. For me, this meant acting locally here in the Riverina region of NSW Australia, by learning more about and helping the reclamation of the Wiradjuri language, and so the sustainability of the Wiradjuri culture, and ultimately what this means for the future of Indigenous people in my local community.

Since part of sensemaking was then, and remains always, formed intersubjectively through our human interconnectivity, this reflective exercise must not be reduced to words on a page. In this sense we don’t have time to look back now, only forward. For me and other participants of the Global Assembly, this means we need to shift the mandate for educators and researchers to be stewards of activism in and for critical educational praxis. As most action researchers might agree, this means treading firmly but lightly and respectfully in the company of communities in which we work – with yindyamarra – but treading in solidarity and agency with a stance committed to transformation and activism for the better future we aspire. Regarding knowledge democratization this means that our individual and collective actions be overtly careful, inclusive, open and respectful of local voices and traditions, always acting with prudence and praxis trying to avoid clouding our genuine goodwill with (sometimes) practised colonising tendencies.

Finally, for my part in reigniting the momentum that the Global Assembly evoked in 2017, from wherever you are in the world, along with my Pedagogy, Education and Praxis International Network (PEP) colleagues, I invite you all to visit and participate in a newly launched PEP international initiative called “Education for a World Worth Living in”. This is a five-year international project seeking to explore how education and the enacted commitment to praxis can help all peoples live well, while also ensuring that we as global citizens play our part in (re)creating a world worth living in for all (see tinyurl.com/wwli4a or email for details about how to participate: admin@worldworthlivingin.org ). Wrapping around our PEP endeavour are words expressed by First Nations Elder and leading Australian scholar, Noel Pearson, who in his recent 2022 Boyer lecture (https://iview.abc.net.au/show/boyer-lecture-2022-noel-pearson), said “the world is my culture” – this means we are all equally responsible for its future.

I conclude this essay, as I began, with words from the Wiradjuri peoples.

Mandaang-guwu ngaagirri-dhu-nyal guwayu

Mandaang-guwu is the Wiradjuri word meaning thank you; ngaagirri-dhu-nyal guwayu means I will meet you in a little while, later or after some time. Traditionally, in many Australian Aboriginal languages, there is little use for words such as “goodbye”. Therefore, I note there is no simple way of saying goodbye if we remain committed to continue on the transformative journey that the Global Assembly set us on.

Footnotes.

[1] Wiradjuri is one of 250 different Aboriginal language regions in Australia

[2] In Cartagena, a number of workshops were held on the day prior to ARNA’s 5th Annual Conference for Action Research (co-hosted by ARNA and Universidad Nacional de Colombia [the National University of Colombia], 13th-16th June). The 12 June gathering, co-sponsored by the University of Cartagena, featured nine pre-conference workshops linked to the Global Assembly. The Networks, Action and Knowledge Democracy workshop was one specifically designed for international network leaders who were to be attendees of the Global Assembly for Knowledge Democracy (17th June 2017). It is important to note also that a series of locally-based workshops and seminars were held in many of the network leaders’ home countries as forums to elicit local voices, issues, challenges and questions to be taken up for consideration at the pre-assembly workshop in Colombia and again in the full assembly on 17 June. This prior work provided an opportunity for a broader range of voices to be heard (especially since most network participants would not be able to attend the in-person Global event on the 17th June). For example, participants from countries in the International PEP network (including Australia, The Caribbean, Colombia, England, Finland, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden) attended locally held meetings to discuss issues, test processes, and formulate questions for the actual Assembly event.

[3] The concept of praxis has been an important lever for discussing the purpose of education. Kemmis and Smith (2008, p. 6), for example, suggested ‘praxis’ as that particular kind of practice which is morally-committed, and oriented and informed by practice traditions. They draw from both an Aristotelian understanding of praxis as being about morally right and just conduct -doing what is right in light of the circumstances at the time; and consistent with post-Marxian understandings of praxis as ‘history-making action’ that highlights praxis as action cognisant of moral, social and political consequences – good or bad – for those involved in and affected by it.

References

Boyle, T., Rönnerman, K., Petrie, K., Grootenboer, P. & Edwards-Groves, C. (2022). Acknowledging, negotiating, and reporting ‘uncomfortable truths’ in action research. Educational Action Research. 10.1080/09650792.2022.2044875.

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research. Routledge Falmer Press.

Edwards-Groves, C., Grootenboer, P., & Smith, T. (2018). Knowing Pedagogical Praxis in Twenty-First Century Education. In C. Edwards-Groves, P, Grootenboer & J. Wilkinson (eds), Education in an era of schooling: Critical perspectives of educational practice and action research, (p. 135-150). Springer.

Edwards-Groves, C., & Murray, C. (2008). Enabling voice: The perspectives of schooling from Aboriginal youth at risk of entering the juvenile justice system. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 37, 165-177.

Edwards-Groves, C, & Rönnerman, K. (2021). Generative leadership: Rescripting the promise of action research. Springer.

Groundwater-Smith, S. (2017). From practice to praxis: A reflexive turn. Routledge.

Kemmis, S. (2020). A practice sensibility: An invitation to the theory of practice architectures. Springer.

Kemmis, S. (2022). Transforming Practices: Changing the world with the theory of practice architectures. Springer.

Kemmis, S. & Edwards-Groves, C. (2017). Understanding education: History, politics, practice. Springer.

Kemmis, S., & Smith, T. (Eds.) (2008). Enabling praxis: Challenges for education. Sense.

Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P. & Bristol, L. (2014). Changing Practices, Changing Education. Springer.

MacIntyre, A. (1981). After virtue: A study in moral theory. Duckworth.

Rönnerman, K., Grootenboer, P., & Edwards-Groves, C. (2017). The practice architectures of middle leading in early childhood education. International Journal of Childcare and Education Policy, 11(8).

Stetsenko, A. (2008). Collaboration and cogenerativity: On bridging the gaps separating theory-practice and cognition-emotion. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 3 (2), 521-533.

Stetsenko, A. (2014). Transformative activist stance for education: Inventing the future in moving beyond the status quo. In T. Corcoran (Ed.), Psychology in Education: Critical Theory-Practice (pp. 181-198). Sense Publishers.

Stensenko, A. (2019). Cultural-Historical Approaches to Studying Learning and Development. Springer.

Sumara, D. & Davis, B. (2012). Complexity theory and action research. In Susan E. Noffke & Bridget Somekh (eds) The Sage Handbook of Educational Action Research, (pp 358 – 369). Sage Publications

Sullivan, B., & Grant, S. Sr. (2016). Yindyamarra Yambuwan: Respecting everything. www.sharingandlearning.com.au

Trudgett, M. (2013). ‘Stop, collaborate and listen: A guide to seeding success for Indigenous higher Degree Research Students’. In R.G. Craven & J. Mooney (ed.) Seeding Success in indigenous Australian Higher Education: Diversity in Higher Education, (p. 137-155).

To cite this work, please use the following reference:

Edwards-Groves, C. (2023, February 4). Transforming practices and practice architectures for democratising global conversations: Reflections on the intersubjectivities of the Global Assembly for Knowledge Democracy. Social Publishers Foundation. https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/knowledge_base/transforming-practices-and-practice-architectures-for-democratising-global-conversations/