Project Summary

This project was part of a PhD study exploring the efficacy of a whole school mental health strategy. After an initial Public Patient Involvement (PPI) exercise exploring how best to conduct the research in school, we decided to develop a team of young researchers of 6th form (age 16-17) who would work to collect data alongside younger students (aged 11-15). This was the preferred option for the vast majority of the young people consulted in the PPI. The 6th form young research team (YRT) worked for a number of months with the adult researcher to explore the best way of working with the younger participants. The YRT conducted weekly meetings with the participants on a one-to-one or small group basis looking at the following key questions:

– What do we understand mental health to be?

– How does the school support the mental health of young people?

– What could the school do better to look after young people’s mental health?

After each meeting with participants the adult researcher and YRT members met to record and transcribe the outcomes of their weekly meetings. The processes involved have been illuminating as they have not only highlighted the latent talents of the YRT members but have also contributed towards their personal growth and development. The YRT members talked about feeling empowered by what they had done and also about how their self-belief and self-confidence had grown through the process. In addition, the mentor-mentee relationships that developed between individuals has helped build trust and develop relationships between groups of a school community that would not have come together under ‘normal’ circumstances.

Project Context

Participatory Action Research (PAR) (when done with young people, YPAR) is a collaborative approach to action research where the research team includes community members with lived experience of the research topic. The aim is the re-construction of knowledge through understanding and empowerment; PAR is often carried out with marginalised groups who rarely have their voices heard (Bergold & Thomas, 2012). Whilst some may argue that young people in UK schools do not qualify as a marginalised group, I as the adult researcher would site examples from my 35-year teaching career to counter this. Young people rarely get the opportunity to have a say in the running of their school. Although some schools do maintain student councils, my experience suggests that these are often run by staff with a staff-led agenda that has little real impact on the young people or the institution. I would therefore argue that young people can be viewed as a marginalised group within a school setting.

The research team had concerns about the extent to which this research was going to be participatory. Being aware that young people are often used as objects of research within a school setting (Erickson & Christman, 1996) the intention was to ensure that this research was conducted from the young persons’ perspective, something not commonly adopted (Noffke & Somekh, 2008). Having completed the PPI work our intention was to then get a critical view of the whole school mental health strategy from a young person’s perspective. As the adult researcher I believed that as young people were more comfortable talking to someone closer to their own age, they would be more likely to give insightful and authentic answers through peer interviews. It was therefore probable that we would get what Morrow and Richards (1996) would describe as “informed dissent”.

Research Process and Outcome

Rationale and Research Process

The process through which this work has taken place is a complex and multifaceted one that is giving us insight to new ways of working with young people in schools. By writing together the YRT and adult researcher aim not only to describe but also to understand the processes involved in working in this way. The project has been perplexing, thought provoking, logistically difficult as well as constructive, since through this collaboration new knowledge has been created that can contribute towards school improvement. Engaging young people in a PAR project can be described as postmodern research. It is about empowering the young people involved so that they can explain and validate their own social world view (Stringer & Ortiz Aragon, 2021).

The project focussed on developing agency through responsibility to enable the YRT to shape the research. The ease with which the team picked up concepts and skills seemed to be a natural process to them but also an inspiration to myself as the adult researcher. Their development as YRT members was uncomplicated and organic, they simply listened, synthesised and acted. At the beginning of the process they lacked confidence; however, as they grew into the work they became bold and assured, being prepared to take chances and learning as they progressed. The learning was not just about the research skills and techniques but about building research relationships with younger students and staff.

Participation and Rights

The level of participation within a given project is important as it is inevitably linked to power relationships and control (Christie, 2020; McParlan, 2021). Research participation is a contentious issue particularly where young people are concerned. With YPAR, however, what is agreed upon is the need for involvement from those who know and are experts within their own lived experience. This is therefore so much more than demonstrating that young people are ‘involved’ in a decision-making process but is about ensuring that when decisions are to be made, young people are listened to so that their views can be taken into account in actual decision-making.

The debate then moves from what could happen to what should or must happen. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) was written in the 1980s, adopted in 1990 and came into force in the UK in 1992. It is a legally binding human-rights treaty that focusses on the rights of the child. The significance of this is that for the first time children were recognised as full human beings with the facility to fully participate within society (Freeman, 1996). What is more, by signing up to this the UK government is legally bound to apply it without compromise. The Committee on Rights of the Child oversees compliance with the treaty and has on a number of occasions criticised the UK government for failing to apply aspects of it fully. In particular in 2002 it recommended that the UK needed to do more, specifically in schools, to ensure that there was effective and meaningful participation of children and youth (Lundy, 2007).

I would argue from experience that schools find young people’s participation difficult because of a traditional hierarchical adult bias in most institutions. In addition, there are some adults in schools who don’t subscribe to the view that young people should have a say in this aspect of their life. This therefore begs the question of what exactly constitutes participation in schools. Again, drawing on my experience, although many schools have a student council as a decorative participative feature to satisfy an institutional mandate, this can be a dangerous avenue down which to travel. As evidence suggests (Fielding, 1973), having a tokenistic school council is counterproductive. I also would argue that such tokenism verges on being illegal. It has been found that this sort of council has a greater negative effect than having no school council at all (Alderson, 2000). Kilkelly et al. (2005) report students complaining that their school council meetings are heavily staff led with trivial agendas that usually include topics such as ‘canteens’. Students are unhappy with school forums where ‘nothing ever changes’ (Alderson, 2000); they see them as a waste of time. It is therefore no surprise that the existence of school councils or the like is no guarantee of children’s rights (Wyse, 2001).

The work of Lundy (2007) in developing the Lundy Model of Participation is primarily about simplifying how young people can be given an active role in the decision-making process regarding aspects of their lives. Lundy’s principles of ‘Space, Voice, Audience and Influence’ align well with the research design selected for this project. By working as a team that includes an adult researcher, YRT and participants, the aim was to give young people voice and space as well as an audience and influence through meetings with the school’s leadership team; the school has promised to work with the YRT to look at implementing changes identified through the research.

Research Output

One of the project’s success criteria is that learning has taken place through an adult researcher working in close collaboration with the YRT. The findings regarding the efficacy of the school’s mental health strategy have yet to be fully analysed. However, the findings in relation to the processes of a Young Research Team working within a school context are set out by the YRT below.

The link between trust and young people/staff relationships

Aimee Burrus and Mollie Hillary. “In particular, trust was a key aspect which came up a lot throughout the meetings, especially ideas of trust between pupils and teachers. We discovered that trust is a huge part of building relationships and opening conversations about mental health, as participants discussed how the teachers who actively build relationships with them are the ones they can trust and go to for any problems. This became more apparent when we built a relationship upon trust, as participants became more open and talkative through the weeks, again, reinforcing how important trust is to them. This was surprising to us as participants quickly opened up and gave honest opinions in a matter of weeks, showing how building a strong foundation of trust and listening was highly beneficial to the project. Furthermore, we found that actively listening to participants was a key aspect in building relationships and trust, and that this could be applied in the classroom. It seems that teachers who actively support and listen are the ones who have gained most reliance from students.”

The development of trust and confidence through the process

Josh Schollick. “I believe that my participants’ confidence and trust in me has grown a lot since we started the meetings. This is clear through the answers they give when I ask hard hitting questions. This is seen in the depth they provide and how much more confident they are to deliver their response to me … they trust me and have confidence in me enough that they tell me why they feel the way they do about mental health. In my opinion I’ve moved away from being a strange yr12 that talks to them about topics which are difficult to speak with friends about, never mind complete strangers. I am someone who my participants can talk to about the school’s mental health support system, with enough trust and confidence between us that they know they can critique the system without being reprimanded by staff due to what they’ve said in our meetings. This confidence and trust has also helped me develop more as a person.”

Charlotte Greenup. “Through taking part in the project, I have learnt a lot about myself as well as the other students in the school. In the beginning meeting I found it quite hard to communicate with the year 7’s and talk to them about mental health… However, the bond we quickly made surprised me… I feel like we have formed a good level of trust that enabled us to talk more openly … I have found it challenging when I can see that one student has an opposing view to the other but just agrees and it’s then hard to find the reasoning behind their answer. This was more noticeable at the start of the project whereas now it’s noticeable that they will share their views and even debate between themselves to understand each other’s reasonings.”

Aimee Burrus and Mollie Hillary. “…confidence grew not only [among] the participants, but also in the Young Research Team; the trust gained in the first couple of weeks of meetings was very beneficial to us as it allowed us to talk more confidently and have a less rigid structure of planning. Conversations surrounding mental health progressed from a more general wider school level to a more honest and personal level, which allowed us to compare experiences of mental health strategies between pupils in different school years.”

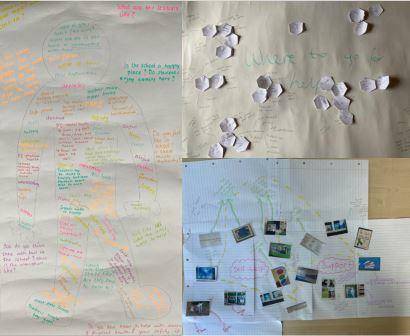

Overcoming the difficulty of building relationships

Abigail Rome and Joanna Liddell. “…with the participants not knowing one another it was challenging to get them to engage and create discussions. So, we used different activities like: “get to know you” sheets, mind maps and hexagon-webs to allow them to think, allowing them to answer the questions without them feeling pressured. Developing relationships and building trust with one another was challenging to begin with, especially since they were scared to talk and express their feelings. We also found that they were scared to express their opinions and just agreed with majority influence. To overcome this challenge, we told them more about ourselves and answered the questions with them, to try develop a relationship so they felt they could trust us which enabled them to express their true feelings. In the end, we found activities that let them think first and then collaborate as a group to work best.”

Using the collaborative process to develop skills and confidence

Susannah Bell. “At the beginning of the project, I found it difficult to communicate my ideas and express my thoughts on the different topics we discussed as I was unsure if what I was saying was applicable. Though as the project grew more into a collaborative process, I felt it was easier to share how I felt about matters – especially during our weekly meetings between the young research team and the adult researcher. We started to analyse our findings as a group during these meetings, meaning there were varying perspectives on how our plans came together and what could be improved, leaving us plenty of opportunities to get the most out of the project that we possibly could. We concluded that the more creative the meetings were, the more open, engaged, and expressive the participants were. I have noticed that the confidence of everyone in the group has significantly improved – not only with creating a rapport with the younger students, but also with creative thinking/ generating ideas, problem solving, and working together as a team.”

How confidence and empowerment have related through the process

Poppy Gregory. “Though the first meeting with my young person without a sheet was slightly stagnant at times I still managed to gather all of the information in a relaxed and fun fashion. The success of this meeting was mostly down to my increased confidence in what I was doing and also helped by the relationship we’d built up using some of the work sheets. If I were to repeat this project, I would probably still use the ‘get to know me’ sheet in the first meeting as this also allowed my young person to focus on something, however, I would be much more confident in myself and my abilities in leading a meeting.”

Katie Elder. “As well as my confidence growing, the young person’s confidence also started to grow as he began to open up more and became more trusting of me, this was very empowering for me. During the start of the project, I used activities and tasks to start conversations easily such as ‘about me’ sheets which were effective in getting to know the young participant, but I gradually gained more confidence in myself and my communication skills and was able to initiate conversations without the support of additional sheets or activities. Empowerment has become a big part of this project for me especially as I have learned many skills which have allowed me to provide better support to the younger person, also seeing the young person’s confidence and knowledge around the subject of mental health in school develop and increase has ultimately improved my confidence and trust in myself.”

How using creative qualitative research methods has enhanced the process

Chloe James and Katie Liddell. “…we decided to join our groups together and use a creative technique to get them talking. We did this by creating a ‘get to know you sheet’ … we also used hexagons and asked them ‘what affects mental health in schools?’ and got the participants to work together to join and link them. This got them to develop a relationship with each other as well as with us, this was the start of us including and developing some creative skills; as we have found over the whole project the participants were more likely to have a conversation with us when they have something to do. Seeing the results from this also increased our confidence as well as improving our own teamwork and communication skills especially, when it comes to talking to younger people who you’ve never met before. Each week we used a creative technique as a starting point and we could see the participants’ confidence around us develop over each week as well as us starting to gain their trust which was really interesting to watch from week to week.”

Cameron McCrea. “I feel qualitative methods really allowed the student I worked with to have an active role in participating in the research, I enjoyed being able to tailor the research techniques to what I thought was most suitable, this was especially important as the student I was working with was young, this was important to consider as they weren’t familiar with the typical language used when talking about mental health. This made the research more difficult as it was harder to reach a clear level of understanding. However, I believe it also provided a non-biased view into how mental health is dealt with in school. Overall, the project has taught me many key skills of how research can be conducted, especially by using qualitative techniques and tailoring them depending on who is involved in the research.”

Eden Norwood. “Initial meetings were conversation based, which involved discussing predetermined topics which wasn’t effective in getting the individuals to engage. To overcome this problem, we decided take a more creative approach, in which we hoped that the children would enjoy more and engage more… we used “get to know me” sheets … in the hopes that … it would make them more confident to discuss their answers and allow us to build a relationship. As well as gaining trust between the young researchers and the individuals, it allowed them to gain trust with each other. The next creative technique … I used was the technique of using hexagons to write down words or phrases linked to the question “what in schools impacts mental health?” We found this to be more effective than the initial meetings that were conversation based, and decided that a creative approach should be taken forward for the rest of the meetings to ensure that all the children enjoyed them and felt able to engage. Ever since introducing the creative techniques and carrying them forward to the rest of my meeting I found that the young people have felt a lot more comfortable in discussing the topic of mental health, so I will continue using these methods in the future.”

Summary

This project contributed to the development of skills and values such as trust, confidence, empowerment, and collaboration – valuable assets that can enhance the lives of both the YRT and participants alike. We believe that there is an opportunity to create a school-based research model that develops older student researchers to work with younger students enabling a contribution to the school improvement agenda. September 2021 will see the second phase of this project begin as further research and development work is to be carried out by the team in order to develop a sustainable model that can be disseminated to other schools across the country.

References

Alderson, P. (2000). School students’ views on school councils and daily life at school. Children & Society, 14, 121–134. Retrieved from https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1493893/1/Alderson_COUNCILS.pdf

Bergold, J., & Thomas, S. (2012). Participatory research methods: A methodological approach in motion. Historical Social Research, 37(4), 191-222. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1801

Christie, N. (2020). Power in schools. In N. Christie, If schools didn’t exist: A study in the sociology of schools (pp. 67-103). The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/12093.003.0008

Erickson, F. & Christman, J. (1996). Taking stock/making change: Stories of collaboration in local school reform. Theory Into Practice, 35(3), 149-157.

Fielding, M. (1973). Democracy in Secondary Schools: School Councils and ‘Shared Responsibility.’ Journal of Moral Education, 2(3), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305724730020303

Freeman, M. (1996). Children’s education; a test case for best interests and autonomy. In D. Davie, R. & Galloway (Ed.), Listening to children in education. London: David Fulton.

Kilkelly, U., Kilpatrick, R. & Lundy, L. et al. (2005). Children’s rights in Northern Ireland. Belfast.

Lundy, L. (2007) “Voice” is not enough: conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, British Educational Research Journal, 33(6), 927-942. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01411920701657033

McPartlan, D. (2021, January 10). Power in schools: An ex-teacher returns as a researcher. Social Publishers Foundation. https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/knowledge_base/power-in-schools-an-ex-teacher-returns-as-a-researcher/

Morrow, V. & Richards, M. (1996). The ethics of social research with children – An overview. Children & Society, 10, 96–105. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1099-0860.1996.tb00461.x?saml_referrer

Noffke, S. & Somekh, B. (2008). Action Research. In B.. Somekh. & C. Lewin (Eds.), Research methods in the social sciences (pp. 89-96). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Stringer, E. & Ortiz Aragon, A. (2021). Action Research (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

Wyse, D. (2001). Felt tip pens and school councils: children’s participation rights in four English schools. Children and Society, 15(4), 209-218.

To cite this work, please use the following reference:

McPartlan, D., Burrus, A., Elder, K., Gregory, P., Hillary, M., McCrea, C., Bell, S., Greenup, C., James, C., Liddell, J., Liddell, K., Norwood, E., Rome, A., & Schollick, J. (2021, August 2). The benefits of young researchers in a school YPAR project. Social Publishers Foundation. https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/knowledge_base/the-benefits-of-young-researchers-in-a-school-ypar-project/