Summary

The closure of academic institutions in Sri Lanka for a long period due to the COVID 19 pandemic has necessitated a transformation from face-to-face teaching to virtual teaching in the country. The sudden shift to online instruction without research-based strategies or training has resulted in bringing back the ‘lecture method’ of teaching, this time to online instruction, despite the many shortcomings of this approach. Utilizing unique online environments, this research sought to answer a question: “How can teacher-centered online lessons be transformed into interactive teaching-learning processes?” This action research aimed to develop an instructional model for implementing a school-based professional teacher development training program for student-teachers using an online mode of teaching. Two online workshops were designed integrating Open Educational Resources (OER) in the module. The Design-Based Research model (DBR) was followed as the framework, and the intervention was implemented with a set of teachers in an Education Zone in Sri Lanka. The data were collected using three different tools to report the perceptions of the teachers before, during, and after the intervention process. It was evident that a successful transition could be implemented in online workshops by using OER as they create opportunities for teacher-student interactions and active participation. Sharing this knowledge among educators would be useful to guide the teachers of Sri Lanka to design and develop their own online lessons.

Research Context

The Ministry of Education in Sri Lanka is structured with several layers of accountability with school, divisional, zonal, provincial and national levels. An education zone is comprised of 100-150 schools according to geographical areas. The Negombo Education Zone (NEZ), in which the current study was conducted, is responsible for educational planning, administration, and school development at the ground level of the local schools. In each Education Zone, a Professional Development Center for Teachers (PDCT) is located and is responsible for conducting efficiency development modules, school-based professional teacher development (SBPTD) programs and pre-service training sessions for professional development of the teachers who work in the schools of the respective Education Zone. Lecturers of PDCTs around the country used to follow only the face-to-face teaching method in conducting programs for the teachers of respective education zones. Although online education has been spreading around the world parallel to other global technological developments, it was not extensively practiced in the teacher education of PDCTs in Sri Lanka. However, as a strategy to overcome social distancing due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Sri Lankan educators were compelled to start online teaching without any advance training of professional development.

As a teacher educator who works in the PDCT of NEZ, when the use of online teaching was mandated, I was faced with adjusting to online teaching to conduct modules for the professional development of the student-teachers in NEZ. While delivering the online lectures, without a single prior-experience or training in online education, I realized that I was following the teacher-centered lecture method, making the student-teachers merely passive listeners. Sometimes I found that, although the names of the student-teachers appeared on the screen as participants (establishing their attendance), most student-teachers were not taking part in the workshops. When sharing my experience with lecturers who work in other PDCTs, I found that the ‘lecture method’, which was rarely being used in face-to-face classroom teaching due to its many shortcomings, had become the main method of teaching delivery online. Consequently, I was motivated to find a solution to the problem of “How can the teacher-centered online lessons be transformed into interactive teaching-learning processes?”

Research Goal, Method, and Outcomes

Research Goal and Rationale

As a remedy to overcome social distancing due to the pandemic, teachers all over the world were compelled to move from the traditional classroom to the virtual world, and this sweeping alteration brought about a drastic change in the use of various digital platforms and applications (Hayashi et al., 2020). Many studies provide evidence from various global contexts that standards for online teaching and the quality of online education were debatable when educators initiated this endeavor without proper training (Allen, 2006; Zhao, 2003). Hence, in this action research, I prepared and conducted a module aiming to provide training using Open Educational Resources (OER) in online teaching.

OERs are teaching, learning and research materials that are in the public domain and they include a set of enabling policies, practices, resources and tools such as texts, images, video, songs, media, worksheets, games and other digital assets. Further, they are freely shared with the intention of improving the accessibility, relevancy, quality and effectiveness of education (Atkins et al., 2007). Hodgkinson-Williams and Arinto (2017) stated that supporting the adoption of OER has become an organized social movement in recent years and this global movement encourages participatory and personalized learning by limiting barriers to accessing teaching and learning materials that are available on the Internet. Karunanayaka and Naidu (2017) stated that since the concept of OER was novel for school teachers in Sri Lanka, an intervention was essential to support integration of OER in their teaching and learning. This action research attempted to provide support for a set of selected teachers in NEZ to integrate OER in the teaching-learning process.

In UNESCO guidance for school closure, several recommendations have been provided for stakeholders of education around the world to plan distant learning solutions (Huang et al., 2020). Likewise, the Ministry of Education in Sri Lanka has implemented various alternative programs in order to continue the process of teaching and learning through distance and online education methods. Greenhill (2010) stressed the need for successfully aligning technologies with content and pedagogy standards that represent 21st century knowledge and skills. Accordingly, in the current study, the 21st century skills needed to prepare students for the 4th Industrial Revolution were introduced to participating teachers through a School Based Professional Teacher Development (SBPTD) module. Karunanayaka and Naidu (2018) emphasized the need to establish a cooperation between researchers and practitioners, while designing appropriate experiences in a systematic manner. In this action research, the designed SBPTD module was conducted, establishing a culture of adopting OER in online teaching. A key element of the research was to demonstrate an interactive approach to aligning technologies with content and pedagogy standards through the use of OERs in a SBPTD module.

Teaching skills and strategies required for online teaching differ from those needed for face-to-face classroom teaching (Gotanda, 2014). Further, the high demand for online teaching and the lack of training on designing online lessons have resulted in mixed outcomes for online course takers worldwide (Loch & Borland, 2014). Although the need to equip educators with the skills for online teaching-learning processes arose in the education system of Sri Lanka, just as it did in all parts of the world in the context of responding to COVID-19, no single approach or model had been introduced to fill this gap. Hence, after reviewing several studies related to the problem, I decided to explore the effects of an OER-integrated online teaching-learning platform in the Sri Lankan context. The objective of this action research was to report the impact of using OER in making online teaching more interactive and student centered. Research questions include:

(1) What are the perceptions of participants on the impact of ‘OER integration in workshops’?

(2) What is the impact of ‘OER integration workshops’ on student-teachers’ own lessons with school children?

Method

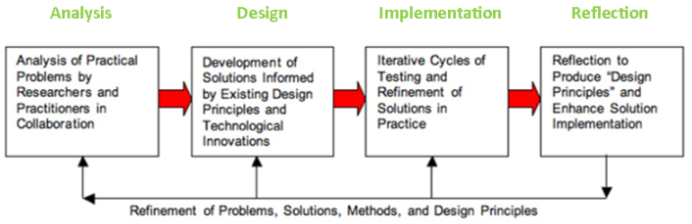

Teachers (N = 25) who completed their pre-service recently at Negombo PDCT participated in this action research. The participants teach in either primary or secondary schools. The Design-Based Research model (DBR) introduced by Amiel and Reeves (2008) was used as the framework of the current research process (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – The Design-based Research model (Amiel & Reeves, 2008, pg. 34)

The model consists of four phases: Analysis, Design, Implementation, and Reflection. In this model, data are collected systematically in order to identify and re-define the problems, and identify possible solutions and principles that might best address them. The multiple qualitative data collecting tools such as semi-structured interviews, questionnaire, and focus group discussion were used at different stages of the intervention process.

Research Process

The research process included four phases.

Phase 1 (Pre-intervention): Analysis

Prior to the intervention, I administered a questionnaire to 25 selected student-teachers. It aimed to gather data in relation to the student-teachers’ perspective on integrating OER and their experience of online instructional practices. I used the gathered data in analyzing the practical problems faced by the teachers and the learners in online teaching. The data indicated that all the participants had the experience of participating in online lessons as student-teachers. All participants, except one, stated that they had negative experiences in participating in online workshops. According to them, there was no teacher-student interaction in online lessons, which was not the case in face-to-face lessons. Further, of the 23 teachers who had experienced online teaching as a teacher, 15 teachers stated that they could conduct student-centered online lessons. Only 11 teachers stated that they had heard about OER, and only 9 teachers of the 11 had used OER. However, the 9 teachers named only a limited number of resources as the OER they knew. I used the results of Phase 1 for identifying the required intervention to overcome the existing situation.

Phase 2 (Pre-intervention): Design

Based on Phase 1 outcomes, the school-based professional teacher development (SBPTD) module was designed. It intended to introduce the 21st century skills framework of Sri Lanka which has been adopted to prepare students for the 4th Industrial Revolution, while integrating OER to make the online teaching-learning process more interactive and student centered. Freely accessible and openly licensed OERs such as texts, images, video, songs, media, worksheets, games, padlets and other digital assets were included in this online module.

Phase 3 (Intervention): Implementation

Intervention 1. I utilized the OER-integrated SBPTD module in a workshop. This workshop was conducted as the first intervention action of the current study and aimed to provide supportive training for the teachers’ transition from face-to-face courses to online courses. Although I informed all participating teachers of the workshop, only 20 teachers participated in the intervention program via Zoom. At the end of the workshop, I held a focus group discussion to analyze the impact of integrating OER in the workshop as a way of making online teaching more interactive and student centered. All the teachers agreed that the workshop was student centered and that there were ample opportunities for teacher-student interaction. A majority stated that they had never known of or used many of the OER integrated in the intervention lesson. “What amazing things are available for us”; “I want to know more about how to use them in my lessons too”; “I’m going to try them in my lessons too”; and “Surely, I’ll be able to become the best teacher of my students by providing the core teaching-learning point with what they like and are interested in” were some of the positive expressions made by the participants. Some negative ideas also emerged: “Many of the students don’t have facilities”; “It seems we have to spend lot of time finding OER”; “I do not have enough ICT knowledge to work with OER”; and “Language is the matter.”

Intervention 2. Addressing the issues identified in the focus group discussion, I organized another workshop to provide knowledge about how to use OER and encouraged the teachers to use OER. The following activities were included in the online workshop: (a) providing links to OER repositories; (b) providing hands-on individual and group activities to identify/search/select OER; (c) supporting lesson planning with integrated OER; (d) encouraging extension activities to be initiated at schools; and (e) encouraging reflective journal writing.

Phase 4: Reflection

After providing necessary guidance to integrate OER in online teaching, I assigned the student-teachers who participated in the workshops to use OER in their own lessons and maintain reflective journals. I myself recorded my own reflections using narrative style. After a week, I conducted semi structured interviews to research the progress in online teaching of each participant, and the teachers shared their experiences of integrating OER in their online lessons. Of the 20 teachers who participated in the Phase 3 intervention, 16 teachers shared their experiences. Four teachers stated that they were unable to conduct online lessons with their students due to some logistical reasons – some had a poor knowledge in handling the device and others did not have their own devices. The problem of online “lecturing” seems to have been somewhat mitigated by utilizing OER as the teachers who practiced OER in their own lessons with the school children stated that they were able to deviate from the lecture method by using OER: “My students were so enthusiastic of doing online games”; “It was a motivation to develop second language abilities too”; “Images and videos made my work easier and more interesting”; “Online lesson plans were very effective”; and “Whether the schools will be started or not, I’m going to continue online lessons.”

Findings and Implications

Based on the focus group discussion and follow-up interaction with the participating teachers, two major categories of findings of the current action research surfaced.

(1) Participants’ perceptions on the impact of ‘OER integration in workshops’

- Integration of OER in the module was a motivation for the teachers to explore and experiment with how the newly learned OERs can be used in teaching their students.

- Overall, the teachers found value in participating in the SBPTD module. They expressed the willingness to know more about OER and to use them in their lessons. The data also indicated that the teachers need more training on online teaching.

- Further, the importance of getting updated emerged in the discussions since the information available on the Internet changes parallel to the rapid development of technology.

(2) The impact of ‘OER integration workshops’ on student-teachers own lessons with school children

- The participants who had experiences in using OER prior to the intervention were motivated to find new OER and made their lessons more interactive.

- The importance of collaboration with other teachers was identified as essential in order to maximize the benefits.

- Maintaining a resource pool for each subject according to grade levels and curriculum themes was identified as a way to manage time.

- Participants expressed the need for sharing this experience with their colleagues and for conducting research on their own practices.

Implications

- I will integrate OER in all my future online modules to provide a practical exposure for student-teachers.

- It is necessary to prepare a module to provide training to the teachers on interactive online teaching delivery.

- It is necessary to introduce OER to teachers and give them practical exposure in how to use them in teaching, in particular how to utilize OERs as a way to make online teaching more interactive.

- Organize quality circles in schools, divisions and zones to discuss the best practices for online teaching and to collaborate on new updates.

- Maintaining an OER pool according to subjects and themes.

My Personal Experience

I was extremely motivated to conduct this research, as I faced a problem when I started online teaching in the professional development programmes for teachers. I found that there was no interaction in the sessions I conducted and it was also very difficult to decide whether the student-teachers actively took part in the sessions. My other concern was that teachers too had to conduct online lessons with no training.

Reviewing literature in conducting this research renewed my knowledge on the use of technology and online teaching techniques. Sharing what I had and what I have found with people who put their heart and soul behind teaching was an interesting experience as they were ready to work hard and go an extra mile to ensure that their students receive a good education. As many are interested in the “shift” to online instructions, the change I tried to make with a few teachers has influenced many people to try the same. The requests I have been receiving to conduct online training on OER are evidence for that.

I also realized that it was problematic to assume that teachers would find the resources available on the Internet. It is necessary to guide them by sharing best practices and links to resources. Further, ongoing collaboration will help the teachers and the administrators. In the semi-structured interviews which were held at the post intervention stage, I too got to know some strategies and OER which I had not used before.

I selected only 25 newly appointed teachers out of the 5,000 teachers in Negombo Education Zone. Selecting a small sample and working only with new teachers are limitations of the study. It is necessary and important to practice this intervention with the senior teachers to investigate their perceptions on integrating OER in online lessons.

Conclusion

The online education that abruptly emerged in the education system of Sri Lanka has now become more resilient against unforeseen future challenges. Many of the teachers who started online lessons had little to no prior training and often taught by trial and error with no research-based online instructional strategies. This action research project was initiated to develop and implement a professional development and training program module focusing on online pedagogy for teachers who are new to online teaching and on utilizing OERs to help strengthen interactive online experiences for students.

This research demonstrated a successful OER-integrated interactive online teaching-learning process. It also examined the importance of providing a proper training to teachers on the use of OER in online teaching. However, there needs to be more replicated studies to examine further the effects of OER-integrated interactive online teaching-learning processes in Sri Lankan education. In the meantime, sharing the findings of the current study among educators would be a useful step (a) to help guide the teachers of Sri Lanka to design and develop online lessons that stimulate active engagement in learning and (b) to generate more evidence as to whether OER-integrated interactive online teaching can be further modified to strengthen teaching-learning procedures across various content areas and grade levels. The productive suggestions brought forward by this study can be a catalyst for creating open mindsets and positive attitudes toward blended learning which is to be implemented from 2023 under new education reforms of Sri Lanka.

References

Allen, T. H. (2006). Is the rush to provide online instruction setting our students up for failure? Communication Education, 55(1), 122-126.

Amiel, T., & Reeves, T. C. (2008). Design-based research and educational technology: Rethinking technology and the research agenda. Journal of educational technology & society, 11(4), 29-40.

Atkins, D. E., Brown, J. S., & Hammond, A. L. (2007). A review of the open educational resources (OER) movement: Achievements, challenges, and new opportunities (Vol. 164). Mountain View: Creative common.

Gotanda, L. (2014). K–12 Online: An Action Research Project on Professional Development for High School Online Pedagogy. University of California, Los Angeles.

Greenhill, V. (2010). 21st Century Knowledge and Skills in Educator Preparation. Partnership for 21st century skills.

Hayashi, R., Garcia, M., & Maddawin, A. (2020). Online Learning in Sri Lanka’s Higher Education Institutions during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Asian Development Bank.

Hodgkinson-Williams, C., & Arinto, P. (2017). Adoption and impact of OER in the Global South (p. 610). African Minds.

Huang, R., Liu, D., Tlili, A., Knyazeva, S., Chang, T. W., Zhang, X., Burgos, D., Jemni, M., Zhang, M., Zhuang, R., & Holotescu, C. (2020). Guidance on open educational practices during school closures: Utilizing OER under COVID-19 pandemic in line with UNESCO OER recommendation. Beijing: Smart Learning Institute of Beijing Normal University.

Karunanayaka, S. P., & Naidu, S. (2017). Impact of integrating OER in teacher education at the Open University of Sri Lanka. International Development Research Centre (IDRC).

Karunanayaka, S. P., & Naidu, S. (2018). Designing capacity building of educators in open educational resources integration leads to transformational change. Distance education, 39(1), 87-109.

Loch, B., & Borland, R. (2014). The transition from traditional face-to-face teaching to blended learning–implications and challenges from a mathematics discipline perspective. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual ASCILITE Conference (pp. 23-26).

Zhao, F. (2003). Enhancing the quality of online higher education through measurement. Quality Assurance in education.

To cite this work, please use the following reference:

Fernando, S. (2022, August 16). Integration of Open Educational Resources in Online Instruction Process: Post-Workshop Perceptions and Actions by Teachers . Social Publishers Foundation. https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/knowledge_base/integration-of-open-educational-resources-in-online-instruction-process-post-workshop-perceptions-and-actions-by-teachers/