Summary

This paper evaluates a variety of curriculum theories and basic principles of curriculum and instruction with the ultimate goal of understanding how curricular orientations can affect the experiences of both students and educators. Upon examination of my curricular beliefs in conversation with the views of employer, the Denver Public School District, I have discovered that a majority of my previous curricular understandings have been rooted in views and practices associated with oppression, otherwise viewed as “traditional” teacher-led literacy instruction. Using the lenses of curricular theory, in this essay I examined my practice for opportunities to shift the paradigm of curriculum to a more equitable, socially conscious, and 21st-century-minded approach to teaching. Constructed on critical thinking and instructor-to-peer collaboration, I provide an overview of my revised approach to classroom instruction. My findings include new approaches to critical literacy, sampling student work after a shift to more student-centered instruction, and a final call to action complete with my plan for creating curricular accountability around student achievement. These findings contribute to the larger educational conversation on the success of public schools in preparing students for life outside the classroom.

Context

I was motivated to share my findings in order to shed light on the ways in which traditional curricular approaches can perpetuate oppression in the classroom and to provide a potential path forward toward a more equitable and socially conscious approach to education. This essay may be relevant to individuals engaged in practices within the domains of education and community-based participatory initiatives as it provides insight into the ways in which curricular approaches can impact the experiences of students and educators. By examining the implications of traditional teacher-led literacy instruction and providing a revised methodology for a more student-centered instruction, this essay may be useful for those seeking to create more equitable and inclusive environments in which to work and learn. Additionally, the call to action for increased curricular accountability around student achievement may be relevant to individuals in any of the aforementioned domains who are interested in promoting positive outcomes for those they serve. Overall, this essay contributes to ongoing discussions about how to create more just and equitable institutions and systems and may be of interest to those seeking to effect positive change in their own communities.

Curriculum: A Tool of the Oppressor

If you feel underpaid, unqualified, and overall unprepared in a career that requires advanced degrees to secure, you are not running yourself ragged through an exercise in futility; you are probably just a teacher working in America. As public educators of the 21st century, we are each one of many cooks in an increasingly overcrowded kitchen. Combine the lack of a clear and united vision for the country’s educational goals with an unprecedented need for differentiation in the classroom, and the concept of designing a curriculum feels downright Sisyphean. As a second-year teacher transplant joining the field with a business background, my relationship with curriculum is complex. While I am a firm believer in relationship-building and practical skill-building, I feel that the way curriculum is typically used serves as a tool of oppression meant to limit student input, push trendy agendas, and reinforce the limiting racial hierarchies our country was founded on. This belief might be better understood when looked at through the lens of curriculum theorist Paulo Freire’s words in his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed: “Education either functions as an instrument that is used to facilitate the integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity to it, or it becomes the practice of freedom, the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world” (Freire, 2000). What Freire is saying here, a sentiment that I echo, is that educational reform is only solved through a reconciliation in the teacher-student dynamic. A reconciliation of the poles of contradiction between the two groups, that is, teachers as promoters of conformity and students as potential transformers of the world, allows for a more lucrative interaction between student and teacher. In the current educational milieu, we see a staunchly traditional dichotomy of givers and receivers of information that doesn’t allow for the practical 21st-century skill building needed for a progressively dynamic world.

Instead, as educators, we often attempt to remedy this dynamic by enacting curricula in humanizing ways. What results is a kind of straddling of the space between best and realistic practice. In academic research, the data is moving faster than public educators and administrators can keep up with. For example, Eisner’s (2002) findings of curriculum as social experiences raised many questions for me about the “real curriculum” for the child. As an English teacher, my lessons are steeped in an implicit curriculum where a student’s takeaway from a text almost entirely depends on their experiences. This could mean that, even with the best intentions and scaffolding, the conclusions I am trying to reach with my material are entirely structureless. While I believe using literature as a mirror in my classroom is an excellent place to start from an equity standpoint, I fear that district-provided literacy standards undercut that progress. For example, students with fractured home lives characterized by minimal parental involvement may struggle to connect to the generational dynamic at the core of the conflict within Romeo and Juliet, thus “missing the point thematically” in the eyes of the district’s standard for evaluating the central conflict of a text. Or when utilizing the gender and feminist literary lens to view the collection of short stories from the book Sabrina and Corina by Kali Fajardo-Anstine, a Hispanic student privy to the nuance of race-based gender inequity is stripped of the opportunity to touch on the dual ethnic and gender dynamics in the text as the curricular approach to literary analysis frames the practice as silos measuring a student’s ability to remark on one lens at a time. I would like to shift my pedagogy to encompass a broader view of literacy instruction that more profoundly connects students’ sociocultural lives and experiences (Muhammad, 2021). I experimented with such a shift in my classroom as part of my university curriculum course assignments; I explored rooting the measurable connections of texts to engagement in and simulations of actions, activities, and interactions in relation to both real and hypothetical social worlds.

The opportunity to experiment with how students connected to a text arose through my English 1 lessons on the play Fences by August Wilson (1986). For context, Fences is the sixth play in a ten-part series known as the “Pittsburgh Cycle” that playwright Wilson created to demonstrate the evolving Black experience in Pittsburg over 100 years. Each play spans a different decade and shares a story reflective of the significant events of the time. Set in the 1950s, Fences tells the story of Troy Maxson and his family. Troy is a hard-working, middle-aged black man who embodies the cycle of generational trauma inherited by many African American children of the time. He continues the cycle of trauma through a series of strained relationships with his sons Cory and Lyons, his wife Rose, his disabled brother Gabriel, and his best friend Bono. In the end, his son Cory breaks the cycle by choosing to forgive the transgressions of his father and thus shed the burden of his mistakes that plagued the family for years. The play frequently uses the n-word, which we prepared for preemptively as a class through a Socratic seminar on the power of words. And while the conflicts, themes, and lessons from the play are still salient today, I began to wonder how the text might be perceived by students of color who, despite seeing the representation through an all-Black cast, may struggle with the negative connotations around how the males are characterized. More specifically, the reinforcement of the absent or neglectful father trope and the perpetuation of the angry black man stereotype caused concern for me. Consequently, weeks 15-17 in the university curriculum course I was taking mirrored my class’s exploration of Act 2 of the play. This allowed me to change how students interacted with and drew meaning from the text. While the activities I had planned while we read Act 1 of the play focused on identifying motifs, characterizing our leads, and interpreting dialogue, I shifted my focus in the final three weeks to incorporate students’ lived experiences as a measure through which they draw meaning from the text. This exploration of “alternative” literacy took form through open-ended writing activities, a shift from plot-based quizzes to cause-and-effect evaluations, and the addition of a new final prompt option that considered cultural biases and allowed students to build an argument based on expression of their lived experience.

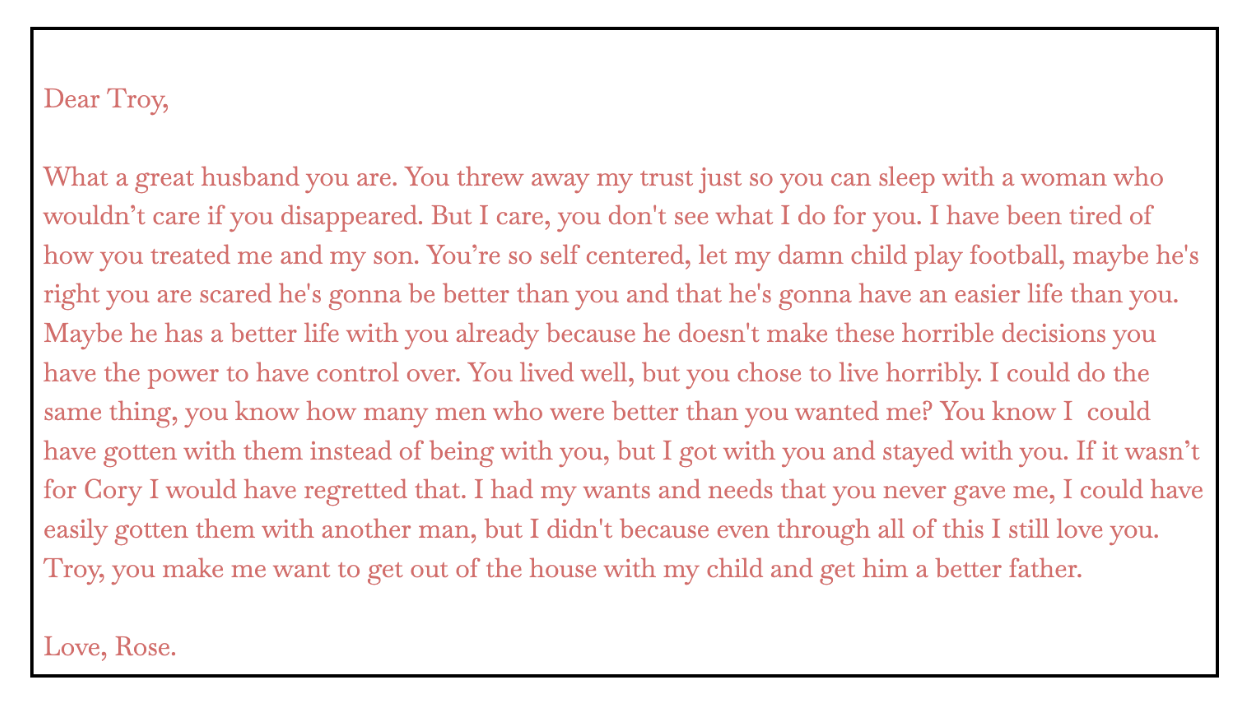

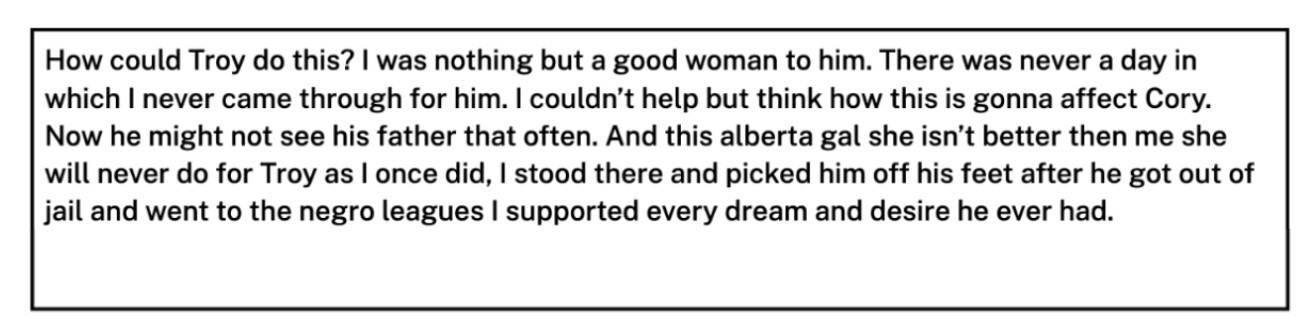

I used three core activities to aid students as we read the final acts of the play together. The first activity category was open-ended writing rather than traditional text-dependent questions. To make this transition, I created a series of journaling tasks that asked students to respond to prompts involving an event that impacted a character in each scene. One activity was around characterization. Instead of asking students to list words or provide evidence to describe how the character Rose changed throughout the play, I asked them to journal from her perspective. The prompt was, “Pretend that you are Rose and have just been told not only that your husband has fathered a child by another woman but that he wants to continue seeing her. Taking the time period and your financial situation into account, write a journal entry exploring your feelings and what your options might be”. Figures 1 and 2 display some of the rich responses I received from students.

Figure 1

Student 1 Response to the Rose Creative Writing Characterization Prompt

Figure 2

Student 2 Response to the Rose Creative Writing Characterization Prompt

Both student examples met the expectation and standards surrounding writing and speaking to articulate how a character develops throughout a text. However, each student could focus on what spoke to them the most about the character’s betrayal, evident through Student 1’s focus on the emotional fallout from Troy’s infidelity and Student 2’s emphasis on the trauma Troy’s actions caused the family.

The second shift was in how I evaluated knowledge through testing. Previously I had multiple-choice reading quizzes for each scene. I amended this to open-ended questions that test student knowledge of the plot through inferences rather than rote memory. These questions challenged students to connect to the real-world implications of the themes in the play. For example, last year, in my Act 2 quiz, I had the multiple choice question, “Of all the ways Troy considers his family (as a whole), Troy’s greatest feeling toward them is that they are a _____ to him.” The choices were savior, burden, money provider, or blessing. To adjust my evaluation to encompass a broader definition of literacy, I asked this question to students on their assessment instead: “What real-world lesson can we learn from how Troy treats his loved ones? Can you provide an example from either your own life or another book, movie, or tv show where a person acts similarly to Troy? How did that make you think differently about that person/character?” These open-ended questions gave me a much deeper understanding of my students, and their ability to make connections outside of the text showed me a level of understanding that extends beyond the classroom and into the larger lessons I intended students to take away from the play.

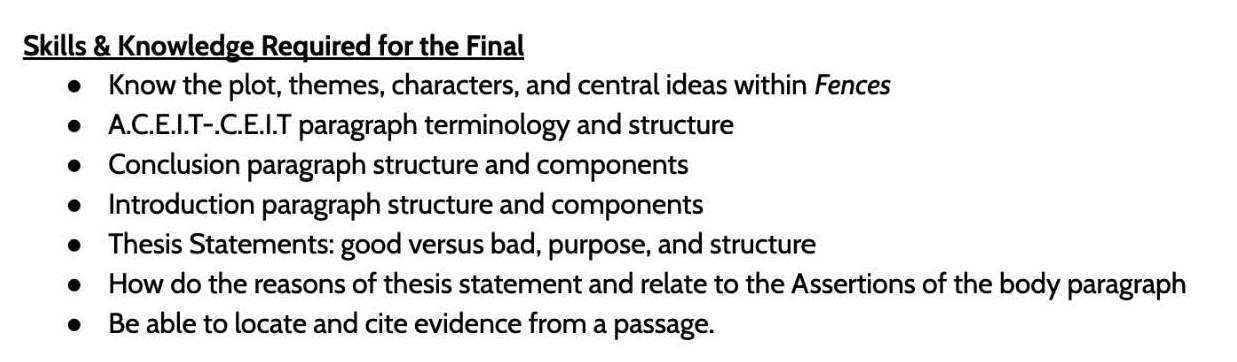

Through weeks of activities and assessments like this, students practiced synthesizing and connecting to the materials through their lived experiences and perspectives. While the department already determined my summative assessment for the semester, an essay, I could add one prompt that embodied this kind of reflection and analysis. In addition to the predetermined prompts, students were given the opportunity to respond to this question for their final essay: “Do you feel that August Wilson reinforces or challenges stereotypes about Black men through his characterization of Troy? In your argument, please provide at least three examples supporting your thinking and use at least one piece of evidence from this article”. This prompt option was not only a culturally responsive approach to the text but also allowed students to connect their experiences and prejudices to the material. My motivation here was to follow through with the idea of representation in literature. It was not enough to provide a text where Black students could see themselves physically in a character. But instead, the chance to comment on how fairly or unfairly they felt that representation to be. Adding this autonomy to the prompt did not take away from a student’s ability to meet what was being measured by the final essay, as seen in Figure 3. Instead, it allowed students to address the implicit curriculum within the unit in conversation with the play (Eisner, 2002, p. 95).

Figure 3

Standards and Skills Measured in My Final Unit Summative Assessment

Qualitatively and anecdotally, these pivots to how I evaluated literacy were hugely successful. There was a shift in my mindset while teaching the second act of Fences that revolved around more big-picture learning. Student work reflected a deeper level of understanding and connection. Turn-in and completion rates were higher than they were for activities in Act 1. Engagement in class discussions was rich and plentiful. My ability to approach the text like this was largely due to the foundational work I did at the start of the year around understanding literary devices, elements of plot, and informative writing structures. However, when that technical work has been done, there are fewer interferences than I originally thought between meeting district-set curriculum expectations and milestones and providing opportunities for students to connect to literature through their own lives and lenses. It seems as if the key to breaking the binaries of literacy is allowing students’ lived experiences to unlock the connections within the text.

At the beginning of my curriculum theories course, I self-indulgently referred to myself as a curriculum critic. Reflecting on my earlier examinations of curriculum scholars and putting them in conversation with my attempts to restructure how I approached learning in my classroom, I have become a sous-chef in this overcrowded educational thought kitchen. I have found myself leaning heavily into the influences of Baker-Bell and colleagues’ (2017) pedagogies of healing. While their focus is rooted in the Black experience in the classroom, her ideas around critical media literacy encompass the curricular empowerment I hope to instill in my students. In my work with the second act of Fences, and now looking forward to the next semester, I embodied their central question at the heart of my activity development, “In what ways can we seek to affirm our students in an effort to occupy (their own) language(s) when combating discriminatory and oppressive texts and movements?” (Baker-Bell et al., 2017, p. 144). As an educator, specifically an English Language Arts teacher, I have resolved that my role is that of a conduit of critical thinking, not a creator. Baker-Bell and colleagues’ central question harkens on my practical takeaways from Schiro’s (2013) Social Reconstruction ideology, where curriculum is viewed from a social perspective. By building opportunities for students to develop meaning from texts based on their lived experiences, beliefs, and the beliefs of others, I pave the way for critical thinkers who approach life by analyzing themselves in relation to society. They can use the written and spoken word to see and understand the problems in society through theme, and with expository writing, they can develop a vision of a better world by challenging predominating ideologies (Schiro, 2013). This kind of structured, student-centered education tackles Eisner’s (2002) paradox of the null curriculum; if what a school teaches is as important as what it does not teach, then in essence, everything is taught when the lesson is centered around a student’s ability to connect to it personally and derive meaning from it. This matters to me, my colleagues, and my students because it repositions the power dynamics of the classroom more equitably. Rather than thinking of myself as the sole keeper and hence disperser of knowledge, like one who adopts the Schiro’s Scholar Academic ideology, I can see myself as a vessel of lived experiences. My colleagues and I bring a host of lived experiences and earned knowledge to the classroom. As educators, it is our social, academic, and moral responsibility to share what we have with students. When it comes to the technical skills they are required to learn to be eligible for their high school diploma in Colorado, my lived educational experiences have equipped me with the tools to teach them. However, how I choose to engage students with these materials can be met by embracing their lived experiences and existing knowledge as a way to make sense of, comment on, and contribute to the learning environment. By adopting a more Socratic approach to most learning, I allow students to fill the null curricular gaps Eisner posits by empowering them to become true mappers of their educational journeys. In doing this, I would also be able to help overcome the suffocating binaries of didactic literacy classifications by directing attention away from Freebody and Luke’s (1990) question of which method affords adequate literacy and instead focus on how students’ interpersonal connections and inferences drawn from texts provide the foreground for practical literacy practices and applications (Freebody & Luke, 1990). This looks like a lot of unlearning on everyone’s behalf. Breaking down the compliance culture and a factory reset of a child’s default to provide the teacher with what we want or expect (Eisner, 2002). Or rather, subverting that expectation with an explicit curriculum that communicates my only expectation as a teacher being that a student strives to connect to our material in a way that speaks to their interests, experiences, and beliefs. All while being open to and engaging with their peers in the hope that we can broaden our thinking to encompass a richer and more discerning understanding of communication, creativity, collaboration, and critical thinking. A tall order perhaps, but a cocktail I imagine the likes of Eisner, Baker-Bell, Schiro, Freebody, and Luke enjoying at a curriculum happy hour.

Conclusion

There is no panacea to the curriculum crisis in America, made evident even more by some curricular academic theories presenting in direct competition with one another (I’m talking to you, Bloome and Schiro Scholar Academics). But contrary to my introductory statement that our nation’s lack of a top-down united vision for united educational goals makes any efforts towards reform fruitless, through my meager classroom findings I can see that there is more power in the classroom than I initially thought. Educators need to open our classrooms to student voices by providing more opportunities for peer discourse and personal connections to our lessons and the world around them. Student deliverables should reflect their findings and thinking, bolstered by and in conversation with the material they have learned from the brilliant scientists, authors, historians, and mathematicians who came before them. This will require innovation on behalf of teachers as we rethink what summative assessments can look like under this new ideology. We will need administrators to go to bat with the district to communicate the importance of accepting a curricular shift in favor of more modern, practical demonstrations of the standards they set. As educators, we set students’ expectations for what is needed to succeed in life outside the classroom. I make it a point to tell all my students that their grades do not determine their worth in life, but they are their currency right now. And if we choose to see students as more than just vessels; instead, as stewards of society, future policymakers, and social discourse disruptors, I believe curricula reflective of those ideals will follow.

References

Baker-Bell, A., Stanbrough, R. J., & Everett, S. (2017). The Stories They Tell: Mainstream Media, Pedagogies of Healing, and Critical Media Literacy. English Education, 49(2).

Eisner, E. W. (2002). The educational imagination: On the design and evaluation of School Programs. Merrill Prentice Hall.

Freebody, P., & Luke, A. (1990). ‘Literacies Programs’: Debates and Demands in Cultural Context. Prospect: an Australian Journal of TESOL, 5(3), 7–16.

Freire, Paulo, 1921-1997. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Muhammad, G. E., Ortiz, N. A., & Neville, M. L. (2021). A historically responsive literacy model for reading and Mathematics. The Reading Teacher, 75(1), 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.2035

Schiro, M. (2013). Curriculum theory: Conflicting visions and enduring concerns. SAGE.

Wilson, A. (1986). Fences. Penguin.

To cite this work, please use the following reference:

Tocci, M. (2023, May 23). Curriculum: A tool of the oppressor. Social Publishers Foundation. https://www.socialpublishersfoundation.org/knowledge_base/curriculum-a-tool-of-the-oppressor/